The Struggle for Ugljevic Coal

State power plant RITE Ugljevik could find itself with depleted coal deposits to fuel its production. (Photo: CIN)

State power plant RITE Ugljevik could find itself with depleted coal deposits to fuel its production. (Photo: CIN)

A state-owned power plant in Ugljevik could end up without enough coal – the main fuel it uses to produce power. The issue came about as the consequence of the RS government’s decision to hand over the majority of its mineral wealth to Russian investor Rashid Sardarov.

In northwest Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) lies Ugljevik, a small mining town in which brown coal (called ugalj in Bosnian), has been excavated for more than a hundred years.

Most of the coal ends up as fuel in the boilers of Public Company Ugljevik Mine and Power Plant (RITE) which produces electrical energy under the Republika Srpska (RS) Power Authority. Until March 2011, the company had the exclusive right to mine coal.

This changed when the RS government, RITE’s majority owner, accepted a letter of intent from a firm owned by Russian billionaire Rashid Sardarov. The letter asked for a concession license to mine coal as well as a concession for building and the use of new thermal energy units in Ugljevik which would be connected to the power grid of the state power plant.

RS President Milorad Dodik pays a visit to RITE Ugljevik with Rašid Sardarov, the owner of Comsar Energy Group Ltd and his officer Duško Perović who is at the same time the head of the RS representative office in Moscow. (Photo: DW)

RS President Milorad Dodik pays a visit to RITE Ugljevik with Rašid Sardarov, the owner of Comsar Energy Group Ltd and his officer Duško Perović who is at the same time the head of the RS representative office in Moscow. (Photo: DW)

The RS Government approved higher mining quotas for the foreign investor than it had for its own company, RITE Ugljevik. This led to a series of protests by RITE’s union whose leaders say that the public company could run out of coal before it has reached its expected lifespan of 25 years.

After the only unit of the public company shuts down, the two other units will continue to operate. Their majority owner is Sardarov who plans to build them. Four interviewees told the reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIN) in Sarajevo that it was a covert privatization of the energy sector.

“In the RS, the one who gets hold of the energy sector shall hold the reigns of power,” said Aleksandar Golijanin, a geologist who used to work for the RS Power Authority and today is a legislator with the opposition Party of Democratic Progress in the RS National Assembly.

Litigation with Slovenians

Even before the war, there was a plan to build a power plant at Ugljevik with four units generating 300 megawatts (MW) each. Each unit was to consist of a furnace which produces electrical energy by burning coal to power a generator. The units need additional infrastructure that includes: cooling towers, transmission lines, chimneys, chemical labs, pumps and many other elements. The first unit, the only one to be completed so far, was built with the help of the Slovenian power authority in the 1980s.

Construction of the first unit cost $395 million. Slovenians invested one-third of the money. The investment was to be paid back by exporting power to Slovenia. RITE Ugljevik’s paperwork states that the same principle was going to be used to build the second unit; Slovenia invested $60 million of the total $180 million needed.

The war halted both the construction and the supply of power to Slovenia, which has never resumed. The management of Slovenian Power Authority has filed a lawsuit against RITE Ugljevik demanding 1.4 billion KM in remedies. The case has not yet been litigated, and Slovenian officials refuse to discuss it.

In place of the Slovenians, the government started doing business with Sardarov. His Cypress-based firm, Comsar Energy Group Ltd. which was named Comsar Energy Ltd at the time, asked the RS Government for a permit to build two new units in the existing power plant, and for a license to start mining coal reserves needed for their operation.

The construction and management of new units, the investor proposed, was to be turned over to a new joint firm, Comsar Energy Republika Srpska (CERS), of which Sardarov’s firm would own 90 percent, while the RS government, that is RITE Ugljevik, would own 10 percent. The RS government accepted the proposal nine days later and CERS was incorporated four months later.

A photo hanging in the office of Žika Krunić, director of RITE Ugljevik, shows the place where Sardarov plans to build new blocks of the power plant. (Photo: CIN)

A photo hanging in the office of Žika Krunić, director of RITE Ugljevik, shows the place where Sardarov plans to build new blocks of the power plant. (Photo: CIN)

Sardarov’s firm wired 10.5 million KM to the government for the incorporation equity, while RITE Ugljevik transferred the land for the building of the new units to the new firm. The land was worth 1 million KM, and RITE also added to it 100,000 KM in cash. The new firm also got the right to use the existing infrastructure.

Comsar Energy Group Ltd invested an additional 53 million KM in CERS at the end of 2013. This reduced the state power plant’s ownership in the joint company to 1.8 percent, but it still kept the right to 10 percent of the profits, according to the latest amendment to the CERS contract.

The RS government and Sardarov realized that because of the pending litigation with Slovenia it was not possible to continue the construction of the second unit, so they decided to move ahead and build units three and four.

Meanwhile, the investor was allowed to use existing infrastructure of the state power plant, although it was also the subject of litigation with the Slovenians.

Partners, but not of their own will

While the RS government has approved these arrangements, the RITE Union does not agree with the government’s moves and fears that the power plant will end up with insufficient coal reserves. RITE director Žiko Krunić, however, said the government owns the facility and has the right to makes these decisions.

CERS also received a concession to mine two coal deposits: Baljak and the site called “Delići and Peljave-Tobut” in 2011. Research indicates the sites contain at least 68 million of tons of coal, according to CERS paperwork, which indicates plans to mine about four million tons of coal annually.

At the current price of coal, (around 60 KM per ton), that would be worth about 240,000,000 KM per year.

Along with this, CERS asked the government for permission to mine at Ugljevik-East, which led to several strikes and protests by members of the RITE Union, who consider the site theirs.

For years, the power plant has been trying to secure a new source of coal because the fuel is about to run out at its current mine, Bogutovo Selo. The union’s paperwork shows that RITE failed twice in its efforts to secure a concession to mine at Ugljevik East, in 2008 and 2011. The RS Government made promises to RITE but a deal was never concluded.

The government has divided the Ugljevik site in a 30 percent-70 percent split. Ugljevic-East, the smaller parcel, contains an estimated 21 million tons of coal. The larger parcel, Ugljevic-East II, contains an estimated 50 million tons.

Zoran Mićanović, president of RITE Ugljevik Union, said that the company’s management bows to the RS governments’ wishes. (Photo: CIN)

Zoran Mićanović, president of RITE Ugljevik Union, said that the company’s management bows to the RS governments’ wishes. (Photo: CIN)

Ugljevik-East was allotted to the state power plant, while the larger Ugljevik-East II went to CERS.

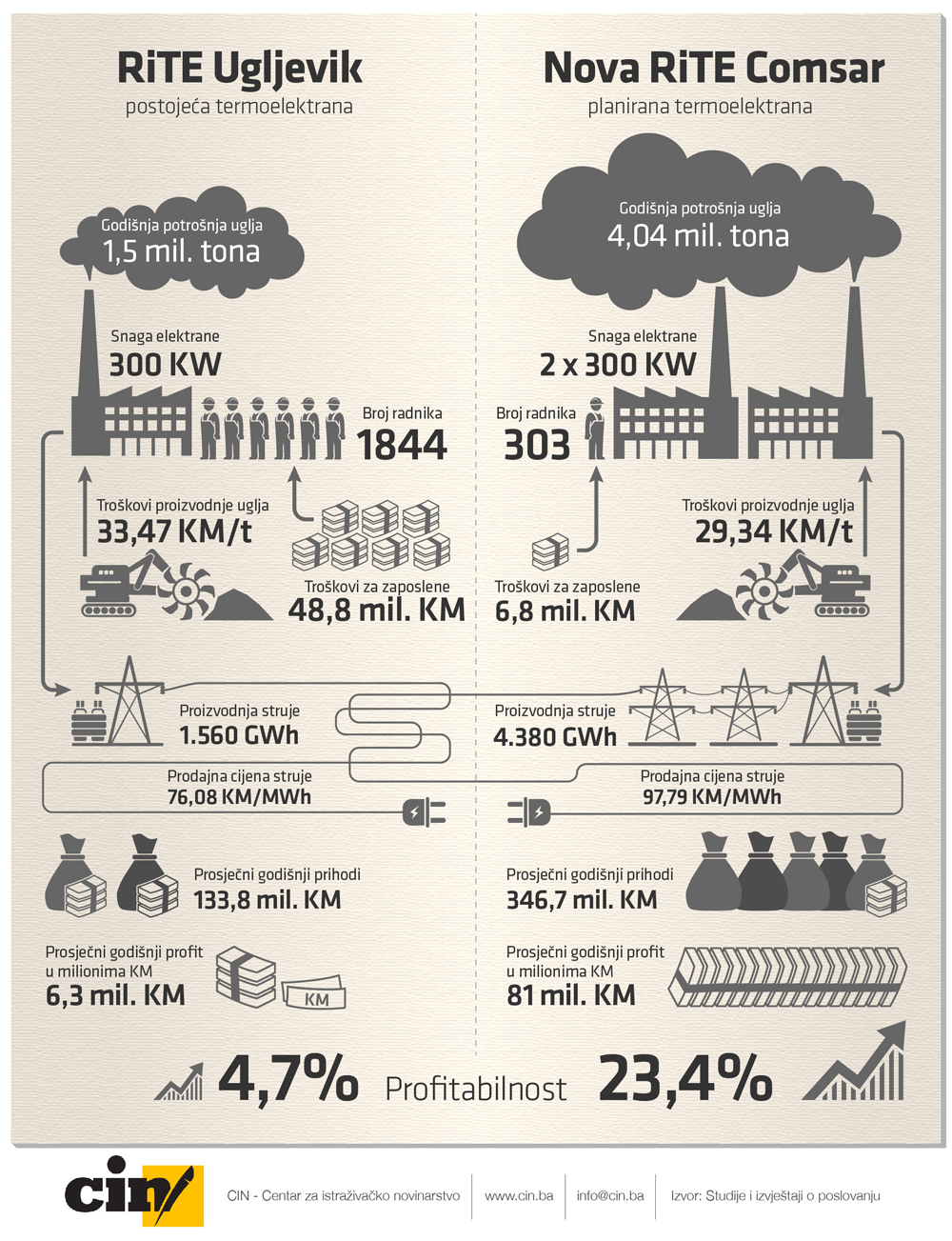

The workers at RITE Ugljevik warn that 21 million tons of coal from Ugljevik-East I will not be sufficient to meet the needs of the power plant for the next 25 years. RITE mines 1.5 million tons of coal a year.

Workers also say Sardarov got much better mining terms than RITE did.

In a call to strike in July 2013, the union claimed that the terms granted to Sardarov were not realistic. They said that in fact, in mining Sardarov would have to remove nearly twice as much soil as was spelled out in his contract, and that there was no space provided for depositing the waste dirt.

After the division of the original Ugljevik-East site, the government had put out a public call for call for applications for the concession license, noting that the site’s production was going to fuel the new plant. The union says the government made it clear that CERS was to get additional points or a 10 percent bonus because it came up with a sole-source contract. RITE Ugljevik Management did not even submit a bid.

Predrag Aškrabić, the chairman of the RS Commission for Concessions, rejects the notion that RITE Ugljevik sought a concession license for Ugljevik-East site for years.

“They just presented their requests as a beginning of their interest. They haven’t submitted the paperwork at all, even though they were supposed to. Only (…) last year they submitted complete paperwork after the government had split the exploitation field in two parts,” said Aškrabić.

Zoran Mićanović, former director of RITE Ugljevik who leads the union, said that the RITE management would obey the wishes of the government as its majority owner, regardless if they’re good or bad for the company.

He said that no one in Ugljevik opposes the investments, but that the government is dealing with Sardarov covertly and without consulting experts. He said the Union will continue fighting until the government reverses course and RITE gets the whole site.

“I don’t think that we have closed this chapter yet. It’s going to be a tug-of-war,” said Mićanović.

Plans Without Study

Local authorities in Ugljevik don’t have much information about what the government plans to do with Sardarov, because a year after his letter was accepted, no feasibility study or environmental impact assessment has been done.

“This was all strange to me from the get-go so we said: ‘wait, let’s see what are the state and local community interests,’” said Vasilije Perić, the head of Ugljevik Municipality. In 2012, he commissioned Professor Aleksa Milojević and his Economic Institute from Bijeljina to do a feasibility study of the investment for the municipality.

Proffessor Dr. Aleksa Milojević has done a feasibility study of the Ugljevik investment and concluded that this was the beginning of the privatization of the energy sector. (Photo: CIN)

Proffessor Dr. Aleksa Milojević has done a feasibility study of the Ugljevik investment and concluded that this was the beginning of the privatization of the energy sector. (Photo: CIN)

Milojević’s study concluded that the RS Government was in fact privatizing coal and electrical power production which was going to significantly damage the industry because privatized natural resources were going to benefit only a narrow group of people, not society as a whole.

No developed country has turned over its coal and electricity production to the private sector because this would lead to higher electricity prices for its industry thus making it less competitive on the market, according to the study.

Mining expert Cvjetko Jovanović agrees. He retired two years ago as the head of RITE Ugljevik’s Development Department. He said that the government was snatching the coal away from citizens and giving it away for peanuts to foreign investors. He believes that this was facilitated by people in power.

Sardarov did his own feasibility study in 2013, two years after having sent the letter of intent. The study confirmed Professor Milojević’s findings that this was a lucrative deal.

Sardarov’s study predicts that the project will make money in all its years of operation and will pay off even if as much as 75 percent of the invested money comes from a loan. The planned lifespan of the facility is between 25 and 40 years, depending on maintenance. The cost of building of the new units was estimated at 1.06 billion KM.

The investor plans to pay back the investment within 10 or 11 years of the new units’ operation by earning around 81 million KM a year from the sale of electricity.

The government had claimed that the investment was going to create jobs for 1,000 workers in the course of construction and 700 permanent jobs in the new units. However, CERS has already signed a contract with a Chinese corporation, CPECC, which will build the units without hiring local labor. Sardarov’s study predicts that 303 workers will be hired in the new units.

The RS Commission for Concession refused to give CIN access to the concession contracts. According to records from the RS Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mining, the firms from the Comsar Group have wired so far around 7.5 million KM in one-time concession fees, and during the lifetime of the concession they are to pay 3.2 percent of its annual revenue in concession fees.

Using the figures from CERS study, this could be around 3.8 million KM a year, but the Ministry would not say what were precisely the foreign investor’s obligations based on the concession for the construction and the use of new units.

Aškrabić, the commission’s president, acknowledges that the politics have a role to play when it comes to awarding concessions.

“If you want someone to back you up, it’s normal that you want to attract his capital,” said Aškrabić.

RS Government Meets Sardarov via a Lawyer

From Sardarov’s letter of intent, it can be inferred that he had been in touch with the government previously and had information about the state of Ugljevik deposits. The Party of Independent Social-Democrats, led by RS President Milorad Dodik, holds the majority posts in the government.

The go-between between the government and Sardarov was Duško Perović, a lawyer from Belgrade. Perović told CIN that he brought Sardarov to BiH and that the citizens should erect a monument to Dodik and roll out the red carpet for Sardarov because of his investment.

Perović said that the critics of this project among the RITE Ugljevik’s employees and citizens were motivated by personal interests as they believe the coal belongs to them.

“They want to profit from it, to resell the coal,” said Perović.

Apart from being a government employee as head of the RS government’s representative office in Moscow, Perović is also employed by two of Sardarov’s firms incorporated in Banja Luka: he is the director of Comsar Energy Trading and the director, with limited authority, of its spin-off Comsar Energy Hydro.

Comsar Energy Trading is owned by a Cypress-based offshore company, Comsar Energy Group Ltd., owned by Sardarov. However, at the time of the letter of intent and the incorporation of CERS, 10 percent of the Cypress firm’s shares were owned by Elnasort Financial Inc., registered offshore in the British Virgin Islands.

According to records collected by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Perović was one of the owners of Elnasort Financial Inc. and one of the important go-betweens helping the real owner to set up an offshore firm.

Perović said that he did not think that he was in a conflict of interest because his position in the two Banja Luka firms and in Elnasort Financial Inc. were just formal and he had accepted them at the insistence of the investor, whom he had brought in and to whom he promised to help start up a business.