The Lasovan family on the Vrbas river near Laktaši is busy working their land. Piles of sand and gravel are being extracted and scattered among trees on the river banks. Some excavators and a truck are shut down until the next time.

Reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) have come across Radomir Simo Lasovan for the second time. He separates fine gravel from the coarse with a machine. He will sell the sand and fine gravel later for around 10 KM per cubic meter, while the useless coarse gravel will be carried away by the Vrbas.

Lasovan does this illegally like the majority of the gravel extractors located up and down river banks in the Republika Srpska (RS), one of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) two entities.

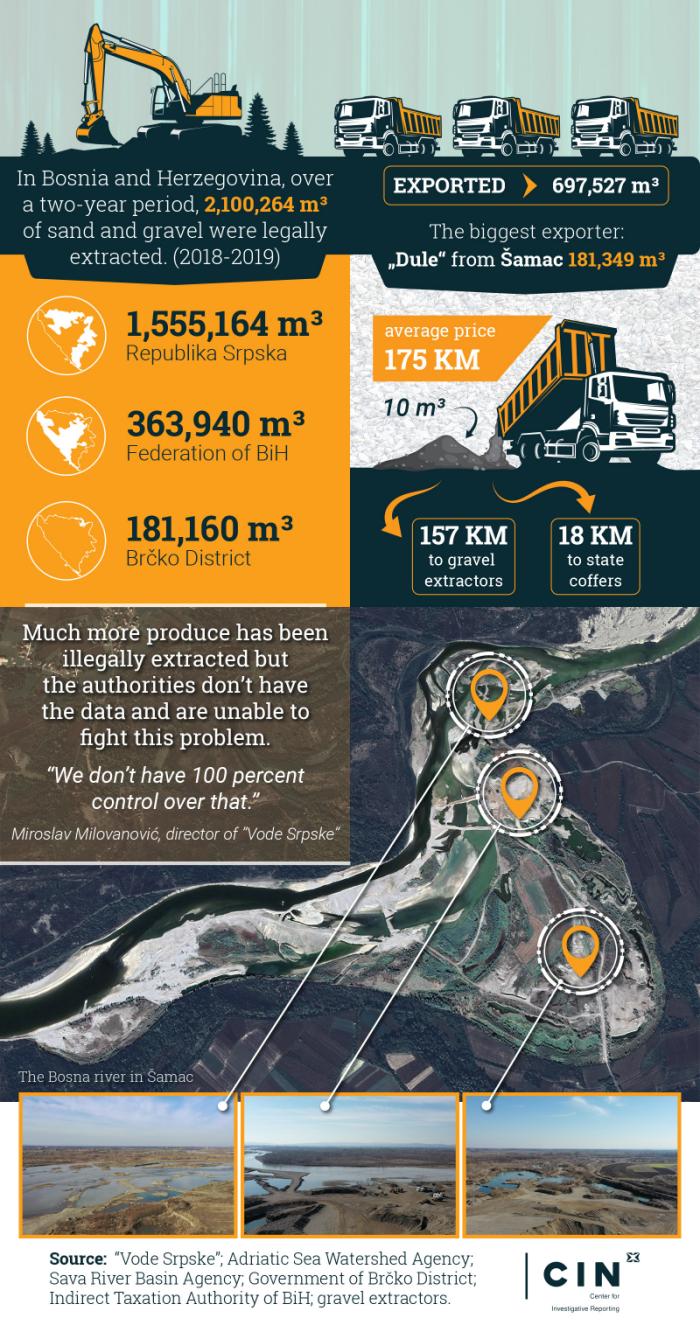

Over the past two years, the state-owned “Vode Srpske” corporation issued 57 permits to firms which reported extracting 1.55 million cubic meters of sand and gravel. This amount of material would be sufficient to build a state road from one end of the country to the other, from Velika Kladuša to Trebinje.

The authorities don’t have precise information on how much of this product was illegally extracted and sold. CIN reporters have travelled fifty kilometers of river banks in BiH and came upon hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of overturned soil, with extraction holes sometimes several meters deep. All of it has been illegally extracted.

This has been going on for years. Officials from the state-owned corporation “Vode Srpske” and inspectors say that they are unable to change things because they lack resources, while punishments are too lenient. Meanwhile, the common good has been appropriated in plain sight of the authorities; river beds are devastated; soil and underground waters are being polluted; banks are collapsing and human habitat risks flooding.

Like Open Wounds

Over several generations the Lasovan family have taken part in sand and gravel extraction. Radomir Simo says that he’s a small fry in this line of business. After inspectors had sanctioned him for illegal extraction, he obtained a permit from “Vode Srpske” in 2016, he said. It was the first and last time that “Lasovan Company” legally extracted gravel from the Vrbas.

Every year, “Vode Srpske” sets out the quotas and locations for extraction of river materials in order to clean riverbeds and safeguard from flooding. Usually, these are places where the river deposits its loads of heavy rocks, gravel, sand, mud and other river material. Companies which sign contracts with “Vode Srpske” must pay 7,000 KM for the paperwork and initial inspection.

In the previous two years, around 4.2 million tons of sand and gravel have been legally extracted in BiH. Around one-third of that amount was exported – 1.4 million tons. The biggest exporter is a Šamac-based “Dule“ which sold more than 362,000 tons, worth 1.8 million KM to neighboring countries.

The firm’s owner Dušan Petrović didn’t want to explain to CIN reporters where he got such an amount of gravel for export. “This is my business secret,” said Petrović.

In 2018, “Dule” did not have an extraction license. Last year, the firm declared that it extracted around 150,000 tons of sand and gravel from the Bosna river bed, which isn’t even half of what they exported.

As a precondition to being granted a permit, companies must rent or own the land and roads used for extraction and transport. This leads to gravel operations continuing to dig in the same places, even when their work permits expire, which leads to uncontrolled bank erosion.

After the extraction, the firms are obliged to pay taxes of at least 1.50 KM per cubic meter of material. In the past two years, they have paid less than 2.5 million KM to the RS authorities.

A dozen holes can be seen on Lasovan’s land, some several meters wide, from which gravel has been extracted and deposited in piles among nearby wood. From there, roads lead to places where Lasovan clears and selects the produce. When the water level is low, a narrow sediment protrudes from the river. One can walk over it to arrive at an extraction site on the opposite bank which is also owned by the Lasovans.

Still, Lasovan said that he doesn’t extract anymore and that all leftover material is from the time when he had a permit. However, he asked reporters not to mention his name until he gets a work permit. “If we don’t get it, we will have to shut it all down, close it and say goodbye to it,” said Lasovan. “Is that fair of me?”

The banks of the Vrbas in Laktaši resemble an open wound. Gravel roads protrude into the river where debris is deposited, while deep holes dug out for extraction of gravel are scattered everywhere. The extractors with whom CIN reporters talked said that “Integral inženjering” destroyed the river banks five years ago, when the company was extracting material for the Laktaši highway. Later others followed, and extraction has been continuous.

However, “Integral Inžinjering“ officials say that they had never done such a thing. “Who is mining legally and who is mining illegally, I’m not an inspector to judge that,” said Integral’s director Slobodan Stanković. “I know that my firm had strict orders to behave in line with the law.”

Regardless of the fact that some plots adjacent to the river are privately owned, no one can obtain an extraction permit to mine the river banks because this is illegal.

Slobodan Vučić, the owner of a Srbac-based “Vuk-komerc” said that this rule doesn’t apply to him. “This is my site, my meadow, my land. I have a right to do what I want!”

Last time the firm was issued a permit to extract gravel from the Vrbas was in 2017. Since there were no sediments found on the site for the past three years, “Vode Srpske” offered “Vuk-komerc” a permit to conduct extraction several hundred meters downstream, but Vučić refused it.

“In those 17,000 cubic meters there are 10,000 cubic meters of stump roots, branches and who knows what else – and now I would need to break my equipment to extract that and clean it and to pay them 1.5 KM per cubic meter on top of that,” Vučić told CIN. “For what? It doesn’t make sense! Well, that’s the point why people won’t clear and do extraction their way.” Instead, he does extraction on his plots of land and claims that there is more gravel in soil than in the Vrbas.

Random extraction and leaving pits in its wake filled with underground waters and debris may lead to pollution of waters that fill sources of drinking water. “This might degrade the quality of underground water for good, which is very dangerous,” said geologist Branko Ivanković.

The Cost of Business

CIN reporters have also visited twenty-odd kilometers of the Bosna river banks in Šamac and Doboj and have encountered hundreds of thousands of square meters of dug out river banks. Underground water filled up the empty pits and light reflecting from their surface created an illusion of a multitude of small beaming lakes. However, reality is far from idyllic.

“This is bad. On the one hand, agricultural land has been destroyed, while on the other hand this is bad for the environment,” said “Vode Srpske” directors Miroslav Milovanović. “There is nothing more to say about it.” He added he is aware of some way worse sites.

The director of the only public company in charge of water and water land stewardship in the RS acknowledges that he has no power over this at the moment. His employees may only “plead with” the private extractors to fix irregularities they come across during official inspections. But they are not authorized to issue sanctions.

Milovanović says that illegal extraction can only be prevented by the police or the Office of the Inspector of the Republika Srpska who are authorized to sanction extractors mining without an extraction permit. However, there are only six water inspectors in the RS, while sand and gravel extraction is just one of their fields of oversight. The RS Inspectorate Office spokesperson, Dušanka Makivić, said that they mostly inspect sites where extraction is legalized.

“It is much easier to work when you receive a piece of information about a site for which a water approval has been issued and they go conduct a targeted inspection,” said Makivić. “However, we unfortunately don’t have that luxury to cruise down the waterway randomly conducting checks.”

Even though the winter is not a season to extract gravel, CIN reporters came across five excavators illegally at work in just one day in a village on the Vrbas. Reporters found these locations by poring over Google Maps.

Inspectors may fine a firm operating without a license with 10,000 KM and the firm’s officers with up to 2,000 KM. Such lenient sanctions are damaging the inspectors’ authority.

In a 2015 report, government auditors also warned of uncontrolled mining of sand and gravel in the Republika Srpska. They came to the conclusion that extractors have already calculated fines issued by inspectors as “the cost of doing business” and that just one quarter of misdemeanor complaints resulted in court-ordered fines. The rest get a suspended sentence, a reprimand or are acquitted.

Inspectors say that the situation has not improved and inspectors face heckling, threats and risk of violence while working in the field, which affects their performance. “Naturally, in this situation inspectors find themselves frustrated, to say the least, because all of their efforts and work and struggle get them nowhere,” said Makivić. The spokeswoman added that a tougher judicial system is needed for sanctions to make sense.

“The reason behind any violation of law is the belief that you will not be adequately punished,” she said.

Extractors are selling a cubic meter of gravel for around 14 KM, and sand for around 21 KM. If they want to operate legally, they need to pay thousands of KM for paperwork, get licenses to access plots, and set aside a percentage of every cubic meter to be paid as a tax.. They know that illegal work pays more.

“He extracts 150,000 KM worth of gravel and then calls inspection so that he would pay a fine after they submit a complaint…Thus one may legalize 200,000 KM with a 20,000 KM fine,” said Slobodan Vučić, who extracts gravel in Srbac. “Why wouldn’t he do that? If I had so much work, I would’ve done the same. Why would I pay taxes when it’s cheaper to pay a fine?”

Checkmate to Public Interest

During the previous two years, the entity water inspectors issued 22 stop work orders against illegal extractors, yet they only filed criminal complaints against two of them. Slobodan Vučić and his firm “Vuk-komerc” extracted gravel from a protected river area. Another firm, “Darko-komerc”, and its owners, Ostoja and Darko Sekimić from Laktaši, are alleged to have extracted some 350,000 cubic meters of gravel, with an estimated profit of 5 million KM. They evaded paying some 500,000 KM in fees to the state.

The police have not yet released a statement concerning Vučić.

Darko Sekimić said that during 2017 and 2018 he tried to apply for an extraction license but was unable to obtain it because his firm damaged the Vrbas banks while extracting gravel in the past. Local residents complained about him to relevant authorities because of their fear of floods. This prevented signing of a contract, and while awaiting a new one, two years have passed.

Despite inspectors’ fines, Sekimić continued to extract: “We have to continue working in order to be able to pay our obligations toward our employees and banks so that something remains for our life, for our family, for our existence.”

Nowadays Sekimić has an extraction license, but he said that he digs out more gravel than what he’s legally permitted. “We get contracts and we are supposed to stick to those contracts and extract a certain amount,” said Sekimić. “Now, some people extract more, while others less. Frankly, one always extracts more and it then sits on inventory.”

“Darko-komerc” is one of the biggest companies in extraction and sale of sand and gravel in this part of the RS. They own nearly all of the land along the parts of the river from which gravel is extracted and thus no other firm can apply for extraction permits at their site. Thus, “Darko-komerc“ meets the main requirement for the permit, i.e. there are no property and title issues. Other extractors with this type of monopoly are doing the same.

“It is impossible to win it! Dodik himself cannot win it because I have put into this all of my efforts and work since 2001 to make an access road to the site,” said Vučić. “That’s only logical that access to produce is worth gold.”

Milovanović, director of “Vode Srpske“ said that his corporation did not notice these issues and did not address them, but he said that they will be more serious in the future when it comes to oversight of sand and gravel extraction.

“With such kind of people, you have to be sneaky, to appease them, to curb their appetites for abuse,” said Milovanović.