Doboj inmate Goran Suvara, serving a six-month sentence for racketeering, paid prison management a bribe of about 3,000 KM and got a temporary unsupervised release.

He was not the only prisoner who did this. Reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) found that at least 11 inmates at Doboj, Zenica and Mostar penitentiaries bribed prison personnel for furloughs between 2005 and 2014.

Prison managers are allowed to give inmates furloughs for good behavior in order to make the prison time easier on them. The CIN investigation has shown that some prison employees saw the system as an opportunity to make easy money, and inmates took advantage of it to commit a new crime or to run away.

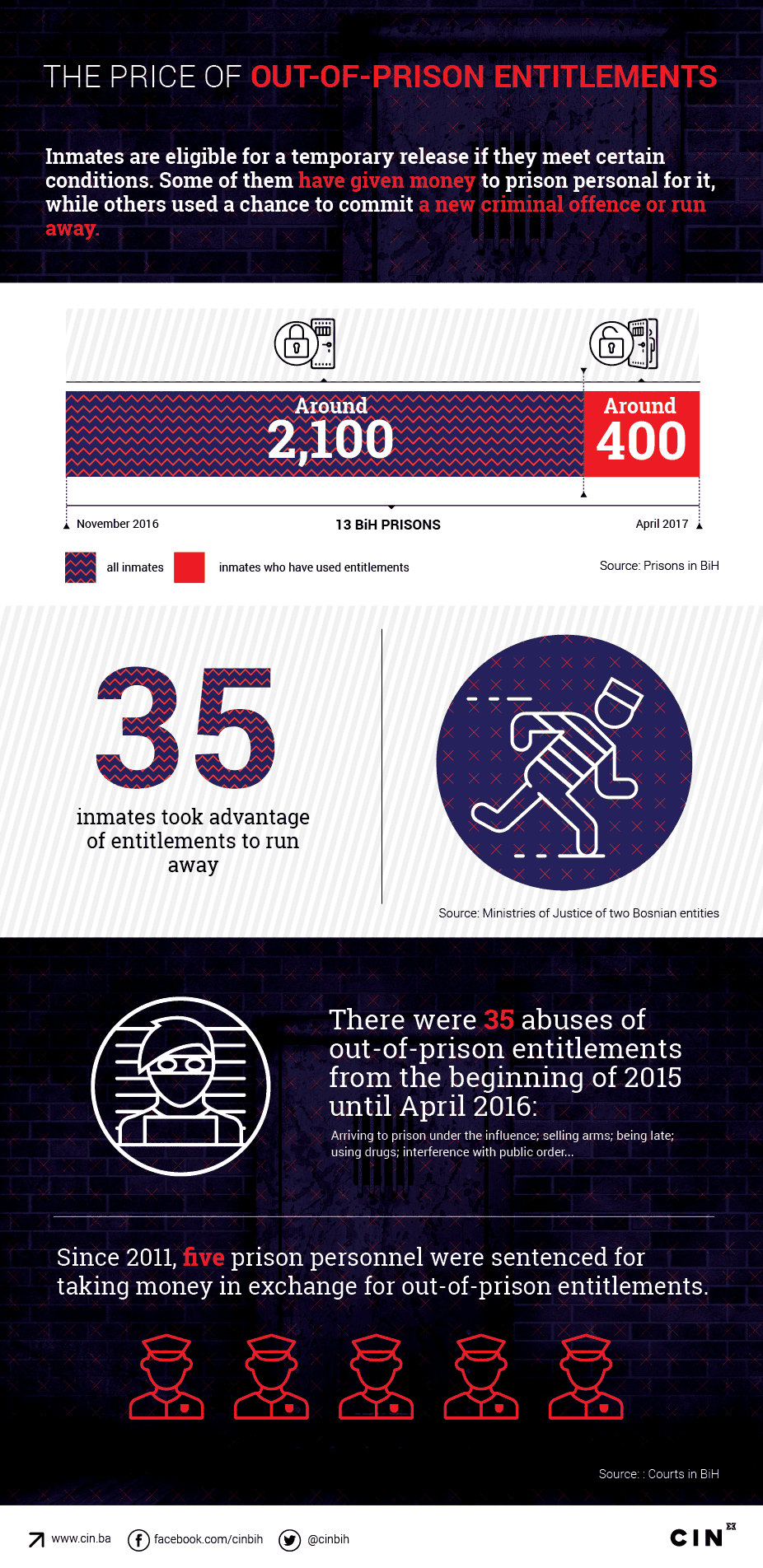

Currently, 35 inmates are at large after going out on a furlough.

The Price of Freedom

Suvara arrived at the Doboj penitentiary in the beginning of August 2008. By then the arrest warrant against him had been closed. While being held in Doboj, Suvara was tried before the Basic Court in Bijeljina on charges of using false ID documents. He had been earlier sentenced for the same crime.

A new and ongoing trial was no obstacle, even though it should have been, for the prison personal to let him stay out of prison over weekends. He was allowed to his first furlough just after a month in prison.

Suvara bought the entitlement. He donated a computer to the prison, and gave around 3,000 KM to a counsellor Mirko Blažanović. He testified about this during the trial of Blažanović and prison warden Milorad Novaković, charged with collecting bribes to provide benefits to inmates or hire prison personnel.

In July 2015, Blažanović and Novaković pleaded guilty and received four- and six-month prison sentences respectively. A court proceeding is underway to convert their sentences into fines to be paid. Novaković said he did not want to speak about the case before the court issued a final ruling.

During the trial, Suvara said that he had established close ties with Blažanović which meant that he “could do anything” – go home when he wanted, intervene on other inmates’ behalf and use a telephone and internet in Blažanović’s office.

Inmate Neven Zec told the police that Suvara spoke to the management on his behalf in 2008. In exchange for benefits, he gave Suvara 400 KM. He was allowed on furloughs even though he was ineligible because of prison rule violations. Zec was a reoffender who served a three-year sentence in Doboj for a robbery.

Doboj County Prosecutor Goran Rubil told CIN that those under disciplinary sanction are not supposed to receive benefits: “As a prosecutor, I’m positive that they have not met the requirements and that they had been granted them only because these officials received money in exchange for benefits. “

It surfaced during the trial, said Rubil, that the prison management awarded furloughs not only to good inmates but also to some who did not deserve them so as not to “rock the boat”.

The current warden of Doboj penitentiary Branko Miletić did not want to comment on the work of his former colleagues. He said that benefits were approved only to the inmates that have deserved them after being vetted by his colleagues, the police and social services.

“Everything is public and transparent,” says Miletić. However, he did not allow CIN reporters to talk to inmates, explaining that the inmates didn’t want to be interviewed. The reporters encountered similar responses from managers of prisons in Istočno Sarajevo, Bijeljina and Foča.

Between November last year and this April, around 2,100 inmates served time in 13 prisons across BiH. CIN reporters talked with 37 prisoners out of 400 who used the benefits. Most said they had seen no irregularities regarding the approval of the release, while others did not want to comment.

“They’ve tightened it up,” said Adi Alić, who’s serving seven years on robbery charges in the Zenica prison.

Free Weekend for Vine and Cheese

Records CIN obtained show that the situation was different between 2010 and 2014 when counselor Sejad Sivac and deputy director for re-socialization and treatment Mugdin Musić worked in the Zenica prison. They took money from at least four inmates including Salkan Džakulić. Even though Džakulić had met the requirements for the entitlement, they would not let him on a furlough before he paid them. For a while he did. Finally, he decided to report them to detectives of the State Investigation and Protection Agency (SIPA). He got in touch with the detectives while on a furlough.

“Sivac told me that weekends out must be paid and that it’s not so easy to get a weekend,” Džakulić told SIPA detectives. During the investigation, Džakulić said that Sivac called him the banker to hint that he was full of cash obtained by passing on counterfeits. He served 7.5 years because of that.

In the beginning of 2014, the detectives set up a trap – they marked the banknotes which turned up in the hands of Sivac, Musić and his cousin Zulfikar Musić, who took cash from Džakulić.

At the trial, they pleaded guilty and received prison sentences – Sivac, nine months; Mugdin Musić, six months. and Zulfikar Musić, five months. Unlike Sivac, the Musić cousins converted the prison sentence into a fine. Mugdin paid 1,713 KM for his freedom, and Zulfikar 1,281 KM.

Mugdin told CIN that he agreed to a plea bargain because he did not believe that he would be acquitted.

“If I were to reach a plea bargain of up to six months, I could pay for it and I would not need to go to prison. This was on my mind all the time”.

The current warden’s assistant for re-socialization and treatment in the Zenica penitentiary, Samir Delić, said that it took time for the case to reveal itself because Džakulić had met all the entitlement requirements. “They took advantage of the man, as people say – by a mile,” said Delić.

Similar things happened in the Mostar prison between 2005 and 2008 when Ivan Kraljević was the head of the Department for Re-socialization of Prisoners. He took money and gifts such as art paintings, spare car parts, a cell phone, cheese and vine from at least five prisoners. Inmates reported him and in 2011 he was sentenced to three years and three months which he served in Orašje and Zenica prisons.

During the trial it was uncovered that Kraljević gave inmate Anto Šesta his passport from out the prison vault for €100 so that the prisoner could go to Germany during his vacation furlough. In his request for the benefit, Šesto wrote that he needed the passport to continue his studies in Split, Croatia: “Mr. Kraljević ordered me to write like this … so that it could not have been seen that I was to go to Germany,” Šesto testified at the trial.

Kraljević told CIN that he was tried because he clashed with the prison’s warden Romeo Zelenika. He said that Zelenika had pressured inmates to testify against him: “He could not work while I was there and he had me moved. I was set up and sentenced drastically,” said Kraljević.

Zelenika denied that. “I had no clashes. This is his version.”

Vacation at Sea Instead of Going Behind the Bars

According to the BiH prison records, 35 inmates are at large because they did not returned from furloughs. One of them was Dominik Ilijašević Como, who served a 15-year sentence in the Mostar penitentiary on charges of war crimes and a murder. Because he worked at the prison’s library, he was entitled to a month’s vacation furlough. He was temporarily released Aug. 23, 2013 but he never came back.

“Before this he used, I don’t know exactly, nine or 10 times out-of-the-prison benefits in Kiseljak without any problems. He always returned correctly,” said his counselor Zoran Rajič. He suspects that Como used the benefits to obtain a Croatian passport with which he crossed the border. An arrest warrant was issued and the BiH judiciary agreed with Croatian counterparts to take over the case.

Last September, the Supreme Court of Croatia recognized the BiH court case and called on Como to report to prison. He complied on May 17, 2017, and is serving the remaining 6.5 years of his term in the Zagreb prison of Remetinec, County Court Judge, Hrvoje Visković in Zadar told CIN.

To run away from prison is not a criminal but a disciplinary offense, and the sanctions are meted out by the prison management. Those range from solitary confinement to losing entitlements up to a year, but the law does not foresee the complete loss of entitlements.

Murder While on Furlough

Apart from fleeing, the inmates took advantage of the benefits in other ways as well: they were late to return to prison; they arrived drunk or high, or they committed a crime while out, according to the data CIN reporters collected from BiH prisons.

Miroslav Marić, assistant to the warden for treatment affairs at the Bijeljina penitentiary, said that there are no guarantees that furloughs might not be abused. “Hypothetically (speaking), one can every time commit a theft and return here without being found out,” said Marić.

It took nearly 10 years to find that Đorđe Ždrale killed Ljubiša Savić Mauzer in 2000 while he was on a furlough from the East Sarajevo penitentiary, according to the court records. The motive for the murder has never been revealed.

Savić’s wife Bojana says that she would prohibit the hardest criminals from enjoying furloughs. She said that if someone asked her whether Ždrale should receive a furlough entitlement in the future, she would answer:

“I’d probably say that I believe in the system and the experts who would make an assessment, but one could get a hint that my answer would be negative,” said Savić.

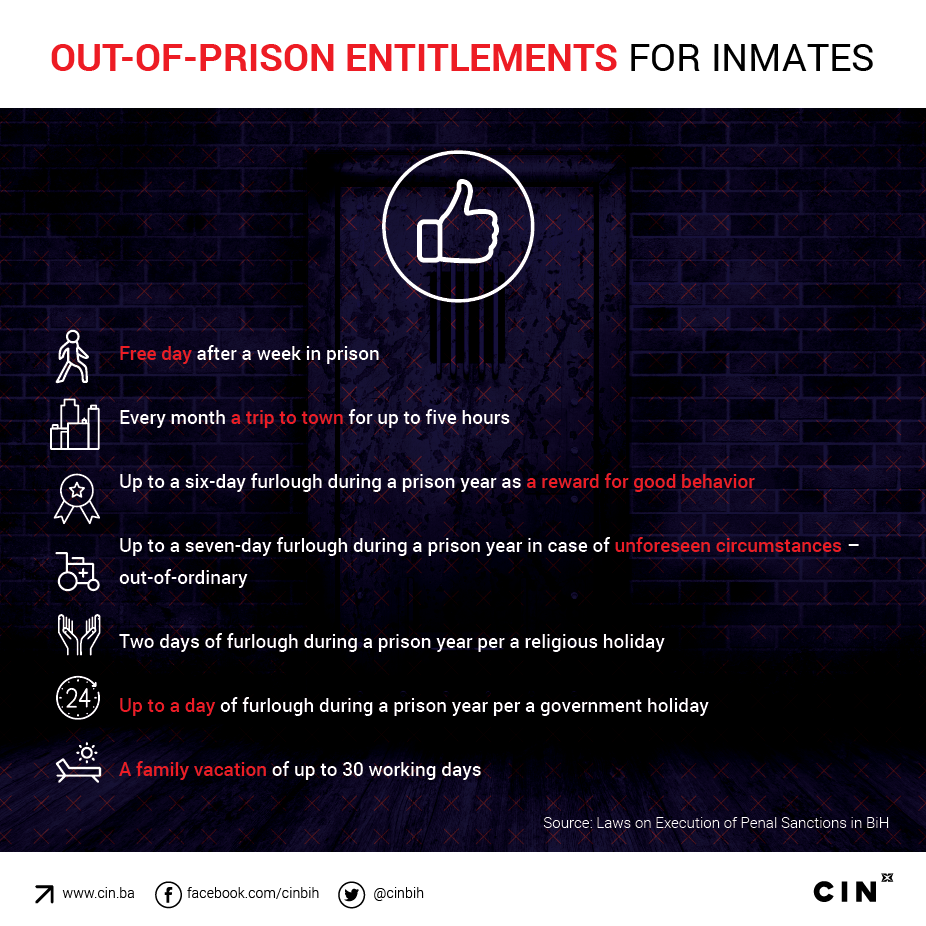

Inmates can use out-of-the-prison benefits once they have served part of their sentences. The law defines how much depending on the length of a sentence.

In 2010, the Court of BiH sentenced Ždrale to 10 years in prison for murder. The state law stipulates that in these cases, the inmates must serve three-fifths of their sentences to become eligible for a temporary release. Other circumstances depend on the assessment of the prison staff that decides if an inmate is going to receive some benefits, of what type, when and until when.

Most of the inmates with whom CIN reporters talked said that a furlough means a lot for their re-socialization, keeping the family ties and easier passing of time behind the bars.