By not investing enough in its universities, Bosnia and Herzegovina has allowed them to degenerate into some of the worst in Europe.

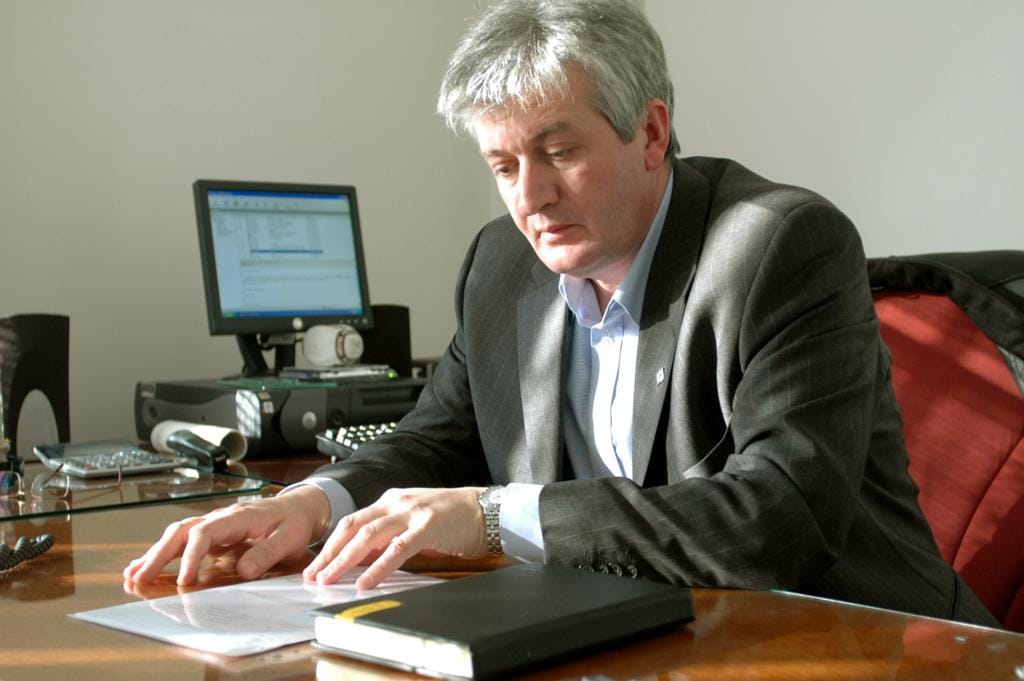

That is a hard and disappointing fact for Professor Božidar Matić of Sarajevo to face. At 70, he has spent half his life teaching university students, and he believes the country’s future hinges on its institutions of higher education.

‘Students are badly educated and they are headed for disaster’ Matić said. ‘And so are all of us.’

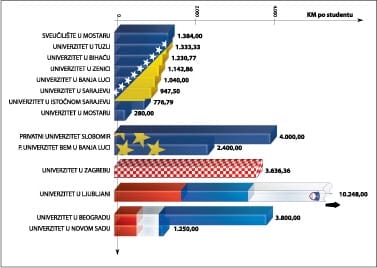

BiH spends 113.5 million KM, or about 1,100 KM per student, a year on its universities. That is not enough to buy equipment, publish research, fill libraries, participate in international exchanges or reform the higher education system.

Croatia, with only 20,000 more students than BiH’s 100,000 spends six times more on higher education. Slovenia has fewer students but spends 12 times more. Even the 150,000-student Serbia and Montenegro system, which is as troubled as BiH’s, spends twice as much.

BiH itself once spent more on its universities. Twenty years ago, Sarajevo University’s budget was twice as big as it is now.

Still, if more money were to fall from the sky tomorrow, problems would remain.

BiH supports a fragmented and bloated bureaucracy in which 13 state, entity and cantonal agencies have a say in higher education.

This system is badly managed and doesn’t account for itself to the public, according to a December report by the Center for Policy Studies entitled, ‘Connecting Education and the Needs of the Economy in Bosnia and Herzegovina.’

In the confusing soup of bosses, real power is held not by at any ministry or university but by individual faculties that compete wastefully against each other.

This leads ‘to costly duplication in teaching (with each faculty organizing its own courses in subjects outside its specialization), administration and services’ the report said.

‘There are illegal decisions made in faculties and the finances are not transparent at all’ said Claude Kieffer, the deputy director of the OSCE Mission to BiH’s Education Department.

‘I don’t know why they are not audited’ he said. ‘It’s all the faculties and all the ministries and all the universities. How do they use the funds given to them? You would need to audit the whole country and each and every structure.’

Faculties hold power and decide the rules

European education experts who have come into BiH in recent years to assess its universities have frequently complained about how hard it is to get information easily obtainable in other countries.

What is the drop-out rate from BiH universities? What percent of professors earn a degree at the same university where they then are hired to teach, a practice that keeps new ideas out of an institution? What do schools spend money on?

No one knows. No one is keeping track.

As one example, Hasib Gibanica, an official with Sarajevo Cantonal Ministry of Finances, said that there’s not much communication between his office and the schools it funds.

‘We get an end-of-the-year report, but we have no way to confirm that it is accurate’ he said. ‘We don’t have access to documentation.’

Money that the faculties collect on their own is particularly difficult to track. How much is collected and how exactly it is spent is unregulated.

What is known is that most faculties pad their public budgets by 20 to 70 percent through a variety of means that range from charging student fees and tuition, renting out extra space, and doing special research projects for paying customers.

The Sarajevo School of Electrical and Computer Engineering has earned a half million KM over the past eight years working on some 70 projects in collaboration with companies like Elektroprivreda and BH Telekom. Kemo Sokolija, dean of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering in Sarajevo, said that faculties have to show initiative when there is no government support.

Professor Miodrag Božić, his counterpart at the Banja Luka School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, said that they have earned around 300,000 KM in projects with Telekom Srpske as their main partner.

‘We wouldn’t have had an internet connection if we hadn’t made that money ourselves’ said Božić.

The School of Forestry in Sarajevo supplements its budget with about 25,000 KM a year earned by renting out vacant office space to Nezavisne novine. Dean Faruk Mekić said professors bring in more money with special projects such as helping companies manage their forest holdings. He’d like to allow part-time students into the school to earn more.

Faruk Čolakovica, dean of the Veterinary Faculty in Sarajevo, said the canton of Sarajevo covers about 70 percent of the school’s costs. To earn the rest professors run animal disease screens, environmental tests and diagnostic tests for companies, individuals and government agencies willing to pay.

Faculties that the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIN) in Sarajevo contacted followed no set guidelines on disbursement of departmental money. Faculty officials do whatever they want with it.

Only once, last year, have government officials conducted an audit to insure that money was being spent properly. An investigation into the Economy Faculty in Sarajevo found significant irregularities.

The school has an 8.5 million KM budget, only 30 percent of which comes from the government.

Faculty officials, auditors found, were handing out housing grants to three employees, paying professor’s bonuses for extra classes and allowing other professors to spend nearly 40 percent of their time outside the school. They found 205,000 KM misspent on housing allowances. In an interview with CIN, the officials said 50 employees actually got grants and that bonuses totaling nearly 255,000 KM were also distributed to an array of employees for Bajram and New Year’s.

Auditors also found that the school was earning nearly 217,000 KM charging students to take exams, a practice educational experts criticize because it encourages schools to fail students. Fewer than 3 percent of students graduate on time in BiH, a rate far below other European schools.

Faculty officials dismiss the auditors as amateurs. ‘I was not able to hold a normal discussion with the uneducated and malicious people they were’ about the fee distribution system said Veljko Trivun, vice dean for financial affairs. He said it was not their job to meddle in teaching.

Fighting over money

BiH clings to a system abandoned nearly everywhere else where faculties make all significant decisions individually and are not subject to control by a university.

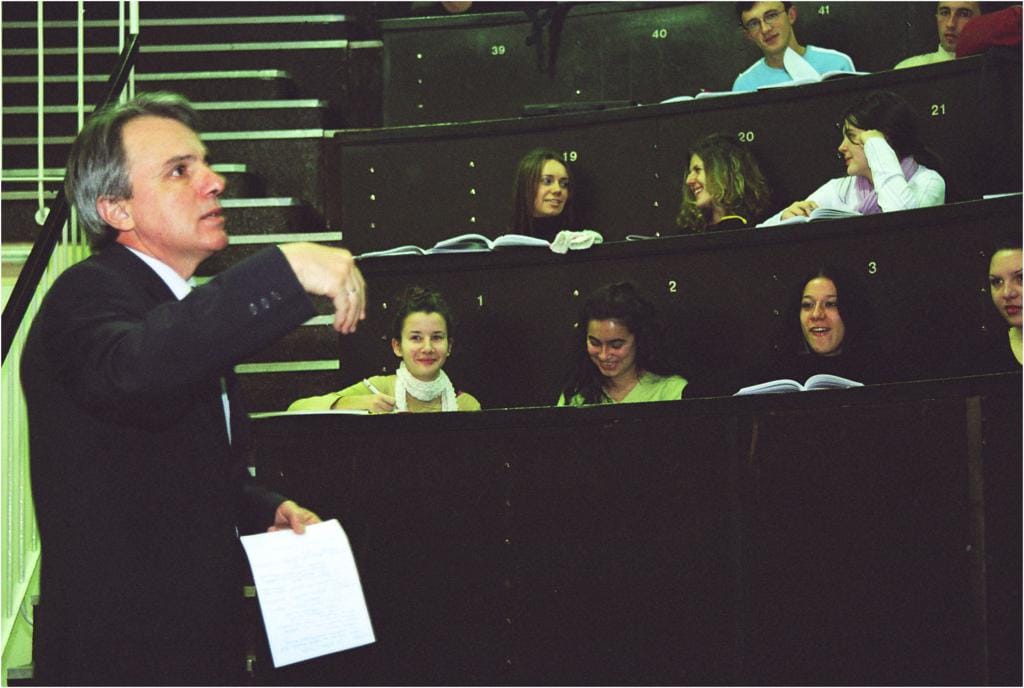

‘I can assure you’ said Professor Jusuf Žiga of the Sarajevo Medical School who served as provost for teaching four year ago, ‘the president of a university can do nothing to anyone at the faculty.’ There is no mechanism for sanctioning professors or employing new staff and faculties control how money is spent.

Faculty power took root under Yugoslavian socialism.

Tito’s regime wanted no threats to its totalitarian authority and universities around the world are focal points of discontent and protest. A strong university could have challenged the one-party ideology, so it was never set up, as Sokolija explains.

Faculties have been efficient in defeating attempts since Tito to bring them under control or organize them differently.

A law passed in 2000 required that faculties deposit money they collect from fees and their entrepreneurial efforts in the state treasury. They are supposed to then submit requests and explanations for money they want to withdraw.

But only three of the eight public universities are complying and the others have not been penalized for breaking the law.

‘They were supposed to transfer to treasury management, but they did not. Thus, they violated the law’ says Mirsada Janjoš, an auditor for the Audit Office of Federation. Janjoš said the universities don’t want to lose control of the money.

Sarajevo University, the country’s largest university which the BiH treasury estimates makes more 30 million KM per year in side deals, has mounted the biggest resistance, pointing to problems schools such as Bihać and Zenica have had trying to collect their own funds back from the state to use for needed repairs and purchases.

Tuzla University works by the treasury rules and according to Mirjana Radić, vice president for financial affairs, has had very good cooperation with the ministry of finances.

Faculty distrust of government involvement in school financing runs deep, in part, because budgets to various institutions are so illogical.

Professor Jusuf Žiga, former vice president for academic practices at the University of Sarajevo, said, ‘One cannot make head or tail’ of how authorities make budgets. They use no standards of size, quality or actual costs when handing out money.

For example, technical and science departments generally are much more expensive to run than humanity departments because of the chemicals and lab equipment they need.

Yet in 2005, the humanities department was budgeted for about 4 million KM – double the amount for the veterinary school and the dental school.

Matić said that political favoritism can explain how some money is handed out at the University of Sarajevo.

The Sarajevo School of Mechanical Engineering received a half million KM more that the School of Electrical Engineering, for example, he said. A former minister of education holds tenure in mechanical engineering.

Emir Turkušić, minister of education in the Canton of Sarajevo, scoffed at that claim as “nonsense. People promoting such views are ‘selling a bill of goods.’

He said his faculty got more money probably because it has more professors and adjunct staff.

Rosters from the two faculties listed on their websites show the opposite. Some 132 employees are listed in the Electrical Engineering Department and 92 in Mechanical Engineering.

Turkušić also suggested that one reason the School of Pharmacy gets 1 million KM compared to 4 million KM for the School of Humanities was that humanities covers a third of the university. But he also said: ‘Faculties are not kindergarten children to get paid the same amount’ he said.

Dean Sokolija in Electrical Engineering grinned when asked about the discrepancy.

‘You know’ he said, ‘politics is like a stove. If you’re too close to it, you’ll get burned. But you shouldn’t be too far away either, or you’ll never get warm.’

Budgets are not proportional to size either. Sarajevo University with 54,000 students has a budget of 38 million. Mostar University of Džemal Bijedić has 10,000 students, but its budget is 10 times not five times smaller.

‘It makes no sense’ said university financial manager Osman Pajić, ‘It’s too little.’

Supporting a bloated administration

It’s hard to justify 13 agencies to oversee higher education in a country of just 3.5 million.

Esma Hadžagić, education assistant to the Minister of Civil Affairs in BiH, called it ‘ridiculous.’

BiH spends 766 million KM on schools from pre-kindergarten through university level and some 4 percent of that – about 29 million KM – goes to support the agencies involved with regulating education. A CIN review showed that 30 to 50 percent of all staffers employed by the public universities are engaged in purely administrative duties.

Trimming administration would increase the amount of money that could go into educational reform. Savings could also come from consolidating universities and faculties.

OSCE’s Kieffer asks whether BiH needs eight universities. In Sarajevo and Mostar two universities catering to different ethnic majorities compete against each other.

‘There can be a lot of savings’ said Kieffer, who believes that BiH must invest in its educational system rather than rely on international handouts.

Emir Adžović, education project manager for the Council of Europe, said the University of Tuzla, where reform efforts have progressed ahead of other schools, has six administrative staffers. In Sarajevo, in contrast, every faculty has its own administrative and bookkeeping staff.

‘Say, there’s five persons at every department times 26 departments. That tallies to 120 people doing a job which in Tuzla is in the hands of six people’ he said. ‘Something has gone wrong here.’

What gets left out of budgets?

To make ends meet, universities have cut deeply into their purchasing budgets, research and investing in educational reform.

Čurković said just 5 percent of Zenica’s 4 million KM budget goes into updating equipment and that is not nearly enough for a school with 4,500 students.

Vojislav Šuka, secretary of the University of Eastern Sarajevo, which has 11,200 students and a budget of 8.7 million, said, ‘We can only dream of science.’

No money has been set aside as well to implement a wide-ranging reform known as the Bologna Process. The intent of this process, which BiH committed to in 2003, is to improve and integrate universities throughout Europe.

Sarajevo Cantonal Ministry of Education has not allocated a dime for the implementation of Bologna Process at the oldest and the biggest national university.

Turkušić said that everybody is talking about Bologna Process, but few know what it is all about.

‘Take an old Corvair and put a Mercedes sign on it and start telling people that it was a Mercedes – well, that’s the state of Bologna round here’ said Turkušić.

Milenko Blesić, a professor at the Sarajevo Faculty of Agriculture, estimates that teaching costs will go up 30 percent a year with the modernization that Bologna demands.

That money would go for more hands-on training, which means buying more equipment and materials, better libraries, and teachers who assign and grade writing exercises, which takes more time than straight lecturing.

Croatia allocated about 18 million KM in 2005 to go toward Bologna improvements.

Cutting costs and raising new revenue

University officials say that budgeting and inefficient use of funds must improve.

One method might be to revive a national higher education fund similar to one that existed before Yugoslavia broke apart. The idea is different from paying money into the state treasury along with every other institution in the country.

Arifa Čurković, secretary of the University of Zenica, says: ‘That fund was in place before the war and we just need to copy the idea.’ Money collected by faculties would be put into the fund and disbursed according to rules set and observed by all. Funds would not be useable for anything but education.

Budgets, set by one unified agencies rather than cantons and entities, would be transparent and fair across faculties.

Setting up such a fund is likely to be politically difficult, though easier than consolidating universities.

Another way to save money would be to centralize purchasing. Rather than have each faculty negotiate for the one or two computers they need, a central office could buy dozens at a time, thereby getting a cheaper price.

The century-old Belgrade School of Medicine is pioneering in this region a well-loved method of raising money used by American and other universities. A year ago the school began gathering data on former students and is now building an alumni association.

Nataša Ognjatović, the association coordinator, said former students who have ended up in universities around the world are interested in paying back their old school out of nostalgia and gratitude.

So far, the association has set up student exchanges and collaboration on scientific projects, but fund-raising to bring in money for the school is a possibility for the future. Former students in Canada have donated books, journals and equipment for DNA analysis.

Students are an obvious source of additional money for schools. While unpopular, reforms have been instituted elsewhere that insure students pay a larger share for the education they receive.

For example, full time humanities students at Sarajevo University pay 100 KM tuition, while part time students on average pay a year’s tuition worth of 900 KM.

Their peers at the University of Zagreb pay 1,400 KM a year for tuition.

According to Journalism Professor Besim Spahić of Sarajevo University, higher education used to be the exclusive right of the elite. Access to education carries a price tag.

‘Knowledge has its price and if they (students) want it, they will have to pay for it’ said Spahić.