Hasija Šaldić from Gradačac has cared for her sick husband Raif for the past 23 years. Every visit to a doctor is tedious for them. There are days when they have to travel 80-odd kilometers to Tuzla just to grab lab results at the University Clinical Center. Then they return home and wait for their turn to visit the family physician.

“It takes so much time and space. Go here, go over there — you have to give every physician a different referral. And you have to take everything to each of them, and then go back. And if something is missing that I have to pick up again, I have to return another day,” describes Šaldić what visits to a doctor are like.

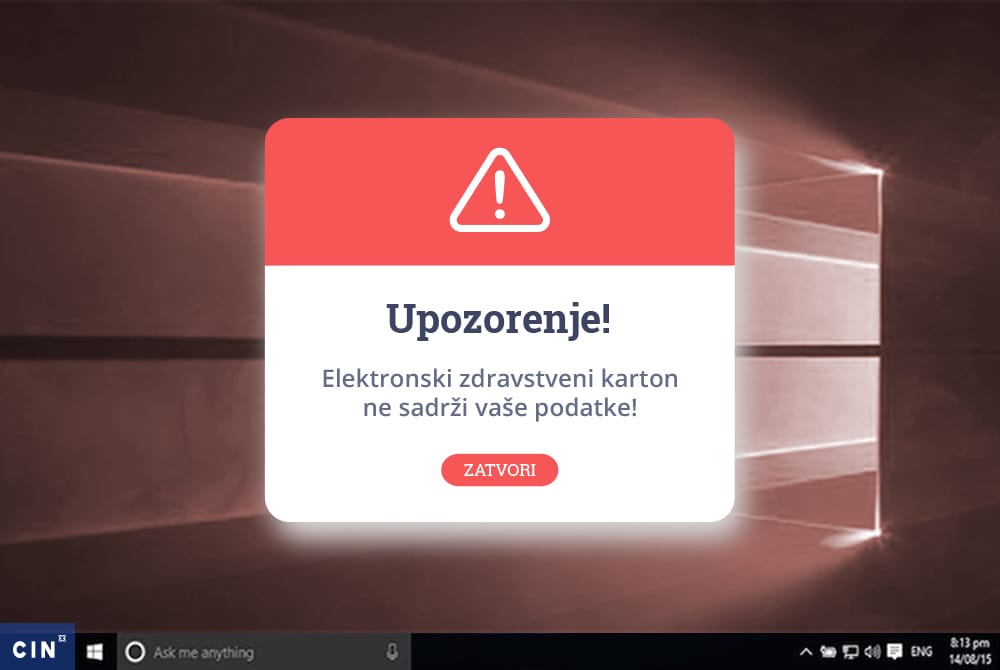

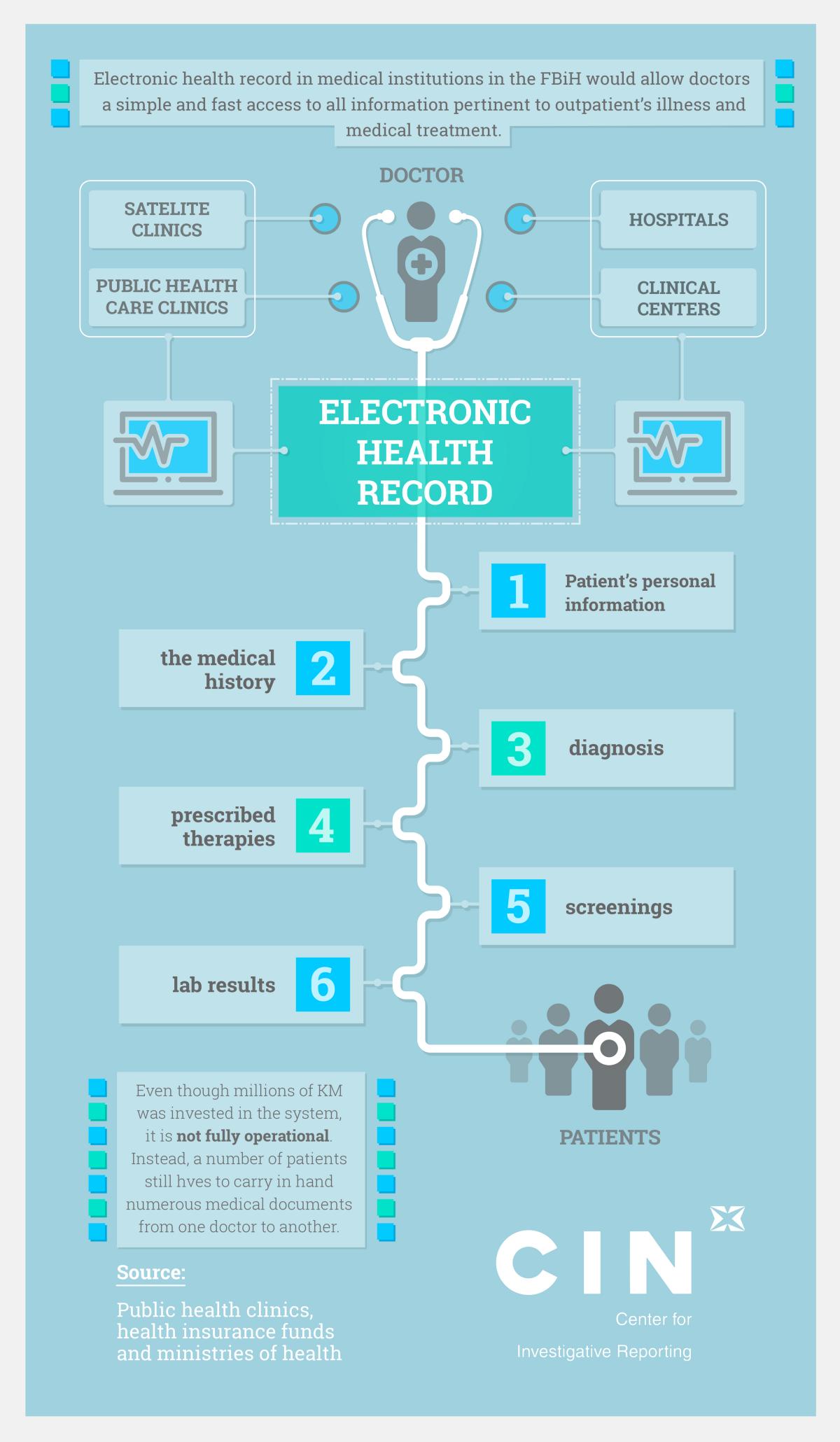

It would make the Šaldićs and other patients’ lives easier if doctors in Gradačac public health clinic used electronic health records. Patients wouldn’t have to carry lab results to and from different health care providers, as records about illnesses, check-ups and medications would have been available on computers — one click away from doctors working for different health care providers. However, doctors in Gradačac don’t do it, even though it’s there. And they are not alone.

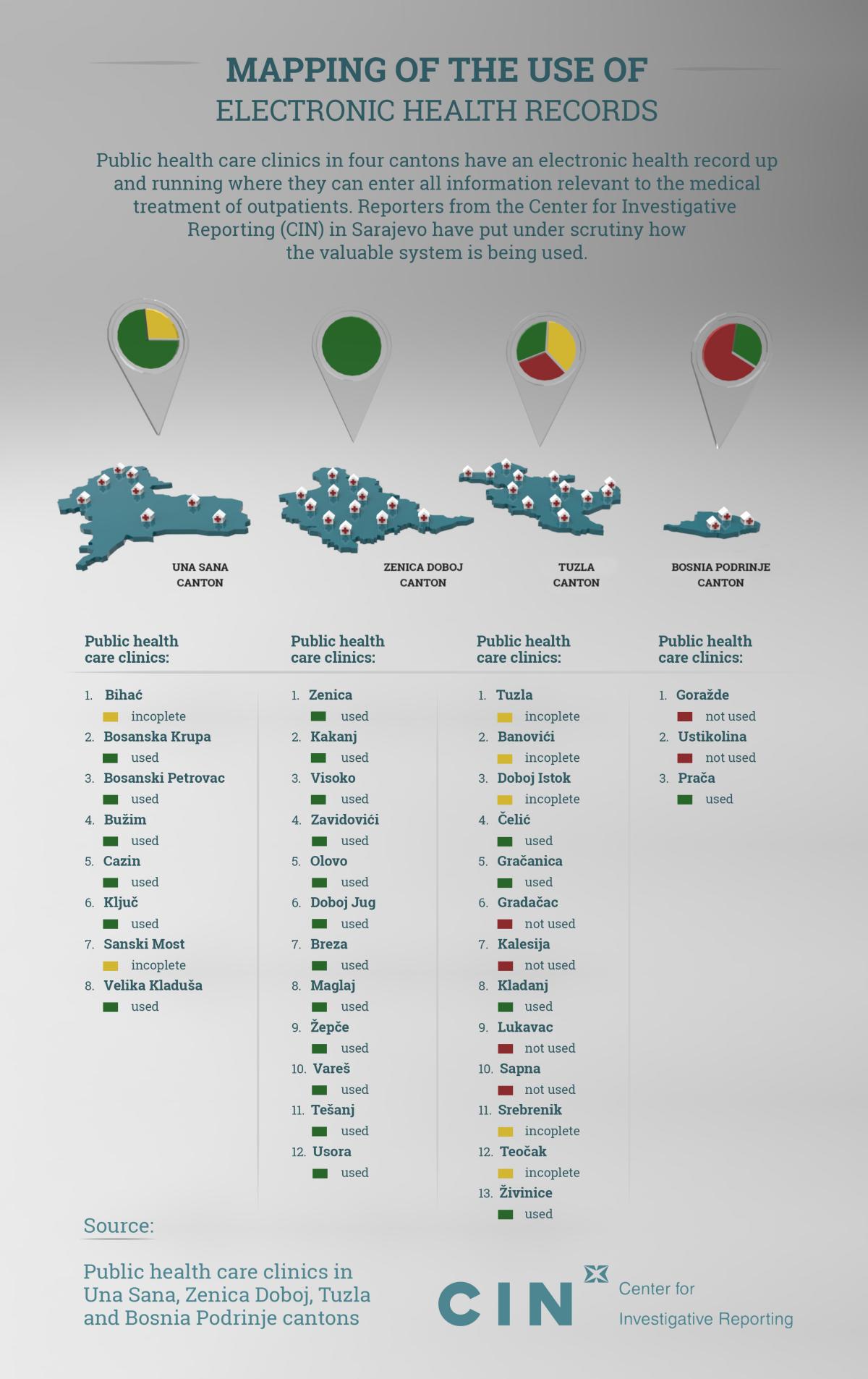

Between 2011 and 2017, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBIH) spent around 20 million KM on the project to improve health care. More than half of the money was spent on digitalization of health care providers. This money paid for computers and other IT equipment for public health clinics. Health care providers in four cantons also got software to get connected and store patients’ medical records in a single place. Today, the system is fully utilized only by the public health care clinics in Zenica Doboj Canton (ZDK).

Regardless whether the system is being used or not, it has to be maintained and that cost is born by the health care providers.

The Center for Investigative Reporting (CIN) in Sarajevo found out that clinics have no choice but to conclude maintenance contracts with the firms from which the FBiH Ministry of Health bought software. One of them, a Sarajevo firm „MedIT“ – secured contracts for software maintenance in three out of four Cantons right from the start.

Director of the ZDK Health Insurance Fund, Mirzeta Subašić, calls this a monopoly. On the other hand, MedIT’s co-owner Samir Dedović says that other software firms also do maintenance of their systems and that such a practice is typical in other countries.

Digitalization on Paper

In 2011, the FBiH Ministry of Health started implementing the project titled Strengthening Health Care. It was financed with loans from the World Bank and the Council of Europe Development Bank. The FBiH government also supported it with some budget money. By the end of 2016, around 20 million KM was spent on digitalization. Taxpayers will be paying for those loans by 2031.

The project’s goal was to provide outpatient’s clinics and public health care clinics in the FBiH with medical equipment and furniture; to give employees additional training, and make patients’ life easier through a simplified protocol for accessing health services by using electronic health record. The FBiH Ministry of Health purchased computers and other equipment and put out a tender for procurement of servers and software in 2014.

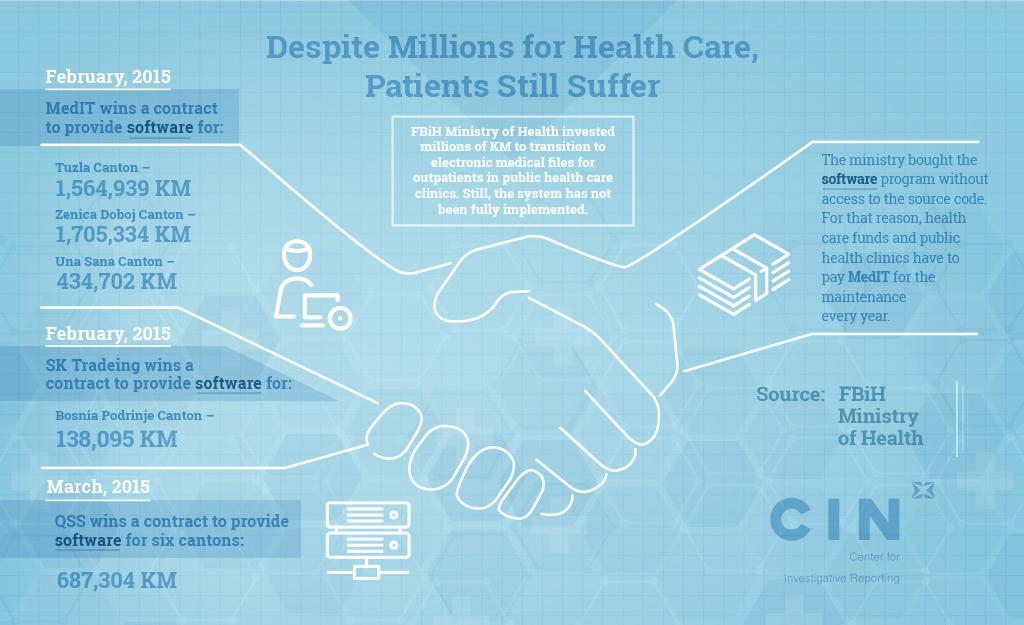

QSS won a contract to provide servers for six cantons in the amount of less than 690,000 KM. Two firms received contracts to provide software – SK Trading for 138,000 KM in Bosnia Podrinje Canton (BPK) and MedIT in Tuzla, Zenica Doboj and Una Sana cantons — for more than 3 million KM. Then the Ministry turned over servers and software to the cantonal health insurance funds.

Sarajevo Canton and Herzegovina-Neretva Canton already had these computer programs so they were excluded. Four cantons did not receive software in the end. Posavina Canton was expecting to get software by means of donation, so the FBiH Ministry of Health decided not to spend the loans on it. West Herzegovina and Canton 10 already used some applications and were not interested in the FBiH sponsored project. Central Bosnia Canton did not receive government’s approval in time and the procurement could not go ahead.

In September 2015, then acting director of BPK’s health insurance fund, Emir Pršeš, came across computer equipment in the corridors. He refused to sign minutes on the takeover of equipment because he didn’t receive a contract for software, he said.

“I didn’t know what this was all about,” Pršeš told CIN reporters. “I mean, I wanted to have a meeting to clear this up, to see the paperwork, to have someone explain to me what this was all about.”

Then the FBiH Ministry of Health staffers asked him to sign documents so that they could wrap it up.

“It was a tense situation, because I saw that those at the FBiH level have put a pressure via government on us to close the deal as soon as possible because they had a deadline by which they were supposed to get this over with.“

Assistant Minister for Project Implementation at the FBiH Ministry of Health, Vildana Doder, does not agree.

The head of Tuzla Health Insurance Fund, Mirsad Hodžić, said that he also found himself under pressure to sign a contract for software and servers worth 1.7 million KM: “We weren’t really included in this – either during the procurement, or during the selection of firms or anything else that has to do with this information system for outpatients clinics,” said Hodžić. “It was all decided for us by the powers-to-be.“

The investment into the health information system worth millions of KM has not yet born fruit, because the problems started as soon as software and equipment were handed down to health insurance funds.

BPK officials told CIN reporters that the electronic health record operated in the canton for six months during 2015. Edin Čengić, director of Isak Samokovlija public health care clinic, said that the system was very good because the doctors could easily get patient records including information about check-ups, lab reports and dispensed medications.

However, some equipment was missing and that was the end of it. Doder denies that. Pršeš said that they did not have enough money to buy more equipment and thus BPK went back to the old system – where doctors filled out with pen information about patient’s health treatment into paper medical files, and patients had to carry lab results and referrals from one institution to another.

“If I send a referral from here, I need it to arrive in Goražde, do you get that? So when a patient arrives there, it should be waiting for him already in computer,” said a doctor from the Public health care clinic in Prača, Enka Burić. “But, it’s not there.”

Meanwhile, SK Trading, the firm that installed software, was closed. A former co-owner Kerim Kapetanović founded a new firm and in 2018. He fixed the software, bought the missing hardware and informed the government and directors of medical institutions about it. However, the managers of two public health care clinics in BPK had no idea that electronic health record has been operational in their institutions for nearly a year. Čengić said that he learned about it from CIN reporters as no one else informed him before. After reporters found that the system in BPK is operational after all, Kapetanović called CIN’s newsroom to say that his employees started using it.

Two years after the software was installed, health insurance funds’ officials informed the Cantonal Ministry that SK Trading did not meet all of its contractual obligations for which it was paid 138,000 KM. For example, the firm pledged that it would train the Fund’s employees to use the application, store data and integrate the new system with the old system.

“We haven’t taken it over; no one tasked us with duties nor provided with an administrator; we cannot log in because we don’t have the application here at the Fund,” Mersudin Krajišnik, an IT officer at BPK’s health insurance fund told CIN.

The FBiH health officials say that no one has complained about electronic health record, but they have also never checked if doctors were using it.

“If in the future the strategic plan and this ministry’s priorities line up, than we will conduct this type of analysis,“ said Doder.

Keeping Records Twice or Caring for Less Patients

Digitalization in Tuzla Canton was a bit more successful, but here as well, no one made it easier for all the patients to use electronic health record. CIN reporters learned that doctors at four public health care clinics were still filling out medical files in paper.

Among them is the Gradačac public health clinic. That’s why Šaldić still has to carry her husband’s lab results and referrals to Tuzla University Clinical Center. She did not know that her clinic used electronic health record.

“That’s a sin and a shame that we have to go around toiling, while that exists and is not being put to use,” said Šaldić.

Gradačac clinic paid MedIT 17,627 KM for system maintenance over two years, even though it did not use it.

“We have an obligation to the Fund,” said director Alma Šakić. She explained that only three out of 19 doctors used electronic health records for a brief period of time. But they stopped using it too.

Even though CIN requested information for the whole year, MedIT provided the records for November only. It was the proof that three doctors in Gradačac have used the system.

In other health care clinics which aren’t using the system, officials say that they don’t have enough computers or time to enter information. Director of Sapna public health care clinic, Edin Jahić, said that a physician would receive around 50 patients a day and would not be able to enter data either into paper medical files or into the electronic ones.

“We have two options: either to continue the way it’s been going on or, the other option is to limit the number of patients to 25 a day,“ said Jahić. The law stipulates that medical files should exist both in paper and in digital form.

A public health clinic in Srebrenik has issues too. The officials there say that they never received a sufficient number of computers which is why they cannot fully utilize the system.

“There’s one computer per four nurses at the family medicine; they cannot physically enter (information) in. That’s why this digitalization is superficial,” said director Ibrahim Zukić. He added that they were saddled with the system that they neither procured nor negotiated. “It’s absurd,” he said.

Tuzla Canton health insurance fund officials are aware of these issues and they agree with their colleagues. “What they’ve installed for us here, I really don’t see much benefit from all that,” said director Mirsad Hodžić.

Assistant minister Doder told CIN reporters that, at the project’s outset, the FBiH Ministry of Health first conducted a survey of needed equipment among public health clinics. Later, some institutions had additional requirements that the Ministry could not fulfill.

“The least that public health clinics’ managements could have done to help with the process of Information Technology development was to buy a few more computers,” said Doder.

Public Procurement without Competition

Even though the Ministry had donated the system, it is not completely free of charge because the medical providers have to pay for maintenance. That’s why every year they have to find contractors that would fix glitches, store data and work on logging issues.

Since the Ministry of Health did not buy the source code that the application uses, public health care clinics and outpatients clinics can only give maintenance contracts to firms that had provided software for the system, because only those firms have full access to it. Thus, other IT firms do not even have a possibility to win a contract.

People CIN interviewed for the story say that source code is expensive and that it’s not usually sold along with this type of software. Software companies do not have an interest in selling it. “Huge money is invested into producing code that one shall register as trademark,” said MedIT’s co-owner Dedović. “That’s how you do business in the market”.

ZDK only started using the system of electronic health record this year. Its officials say that they had put out a tender for software maintenance twice. Both times MedIT won the contract. For the past two years, the canton concluded contracts for maintenance of all cantonal systems in the amount of 418,200 KM.

“When we put out bids, no one else can apply with a lower bid for the maintenance of the system,” said Fund’s director Subašić and called this a monopoly.

Tuzla Canton’s Fund has the same problem. Together with public health care clinics it is supposed to contract MedIT and pay more than 140,000 KM a year for maintenance of the system. However, some health care providers don’t use the system and refuse to pay for its maintenance.

“We don’t have a choice, they are exclusive for us,” said Banovići public health clinic’s director Munevera Bećarević. MedIT’s co.owner Dedović said that the price of maintenance is the same for all institutions and that health insurance funds have picked up the tab to finance the system’s maintenance.