In the pre-dawn hours of Tuesday, police teams wearing fatigues quietly surrounded the Dobrinja apartment of a Montenegrin-born man long suspected of being a drug kingpin in Sarajevo. Outside in the cold morning light, a new black Porsche Cayenne sport utility vehicle that he had been driving sat on the snow-covered sidewalk in front of the building. But the morning calm was soon broken as police raided the apartment. The raid was so sudden, the occupants had no time to react, police said.

Thus started the process of dismantling one of the region’s bigger drug networks believed to be shipping heroin from Afghanistan into Europe and warehousing drugs in Sarajevo.

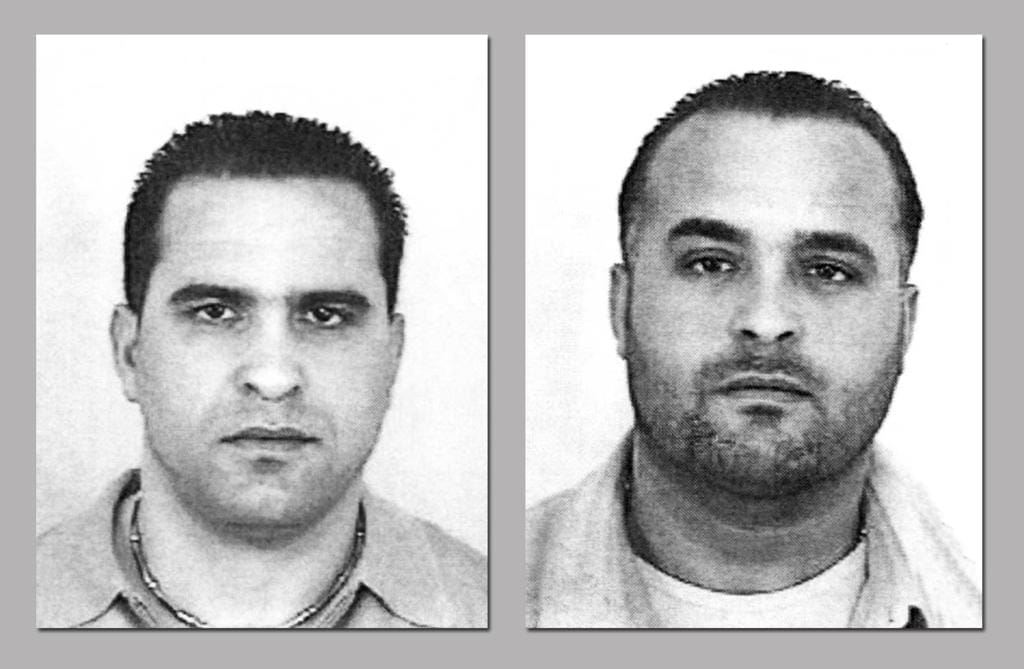

As police were arresting Ljutvija Dacić, 39, in Dobrinja, coordinated raids in the city also arrested his brother Hamdija Dacić, 35, and Acik Can, 38, a Turkish citizen. Three others were arrested and released.

The Dacić brothers have a long history of investigations and arrests related to drugs dating back to the late 1990s. Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) police finally cracked the alleged drug trafficking network based on information gathered from foreign law enforcement agencies in Montenegro, Germany, Slovenia, Spain and Italy, prosecutors said.

‘This case is of vital importance’ said Boris Grubešić, a spokesperson for the BiH Prosecutor’s Office.

Hamdija Dacić was arrested in November 1999 at the Gorica border crossing point with 12.75 kilograms of heroin. Sentenced to eight years, he broke out of the Italian prison after one year on New Year’s Eve with four others. Sarajevo police arrested him in early September 2002, but he was released because Italy could not extradite him; a warrant is still out for his arrest by Interpol in Italy. He was also convicted of forgery in 2003.

Ljutvija Dacić, who changed his name to Haris Zornić—the last name is his wife Latifa’s maiden name―became the co-owner of the firm Majorka in 2001, which owns the Hotel Ekslusiv in Rajlovac. According to a real estate appraisal, the hotel is worth 5.9 million KM. Dacić’s business partner in the hotel is Acik Can, who lists himself in his work permit as a director. Prosecutors are looking at whether the hotel was purchased with drug money.

Ljutvija Dacić was convicted of illegal weapons possession in 2005.

The Dacić brothers also own Piccolo, a cafe in the Grbavica neighborhood of Sarajevo.

In 2002, police from Sarajevo, Croatia and Slovenia investigated a drug network which they suspected was run by Can and the Dacić brothers. They believe the three worked with Esad Ličina from Rožaje in Montenegro, who was arrested in May 2000 with 38 kilos of heroin, Mirsad Rizvić, who was arrested in July 2001 in Graz, Austria, with 28 kilos of heroin and Nermin Akeljić, who was caught with 63 kilos of heroin at a Slovenian border crossing. Prosecutors confirmed the three arrests are part of the case.

Not much is known about Can. He was born in Germany but holds a Turkish passport. He is in Bosnia on a permanent residence status and owns a house in Ilidža. According to State Investigation and Protection Agency (SIPA) records, he is believed to be involved in the transport of heroin from Turkey to Spain and cocaine from Spain to the Balkans.

The Dacić brothers are from Rožaj, a small town near the Kosovo border. The town is also home to Safet ‘Sajo’ Kalić. Kalić is a wealthy local businessman who owns restaurants, hotels and a trucking company and has been accused of drug trafficking by Serbian police.

According to reports, police believe a restaurant in Vogošća was used to repack the drugs for further onward transport to Western Europe. They also believe the Dacić brothers were involved in the transport of several kilos of various drugs found by Croatian policemen and customs officers in January of 2006 in a BiH bus coming from Germany.

Sarajevo has long been a transit point for Afghan heroin and a warehousing center for drugs according to a 2007 US State Department Report.

In the chaos and disorder of the post war years, members of Albanian, Montenegrin and Sandžak clans all picked Sarajevo as a place to warehouse and repackage drugs for shipments on to Western Europe.

From talks with more than a dozen law enforcement officials, reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) found there is strong agreement about who the leaders of these clans are and how they are operating. In the past, police say it has been difficult to gather the evidence needed to arrest them and there has been little political will to support high-profile arrests.

Nermin Legumdžija, head of the narcotics division of the Federation of BiH police, said drug clans stock between 100 to 200 kilos of heroin and marijuana at all times in and around Sarajevo. Heroin comes largely from Afghanistan through Istanbul and is sent along several routes, including ones through Peć in Kosovo, Novi Pazar in Serbia and Rožaje in Montenegro.

Former chief of police in Novi Pazar Suad Bulić has said that drug clans from his city send between 20 and 30 kilos of heroin to Sarajevo each week. Bulić said there are five organized drug gangs in Novi Pazar, and all have Sarajevo connections.

BiH citizens are often used as mules for the drug trade, a practice reflected in data from Interpol that CIN obtained. For example, criminal organizations from BiH tried to smuggle a ton of heroin and an equal amount of marijuana into 20 European countries in the past seven years. In addition, Western European police forces seized 300 kilos of cocaine and 140 thousand Ecstasy pills from BiH citizens in their countries. BiH citizens have been arrested as far away as Brazil, Argentine and Bolivia.

Commonly accepted estimates are that police only intercept between 5 and 20 percent of all drugs shipped, which would mean Bosnia probably is the transshipment point for 20 to 40 tons of heroin alone.

Data from Interpol indicate that at least 280 BiH citizens were involved in the transport and sales of drugs in Western Europe. Ten are under investigation for arranging drug transport. Those arrested, though, have been mostly low-level operatives. Those at the top of the ladder are evasive, and while they may be known to law enforcement, they have managed to stay out of the public eye. Until now.