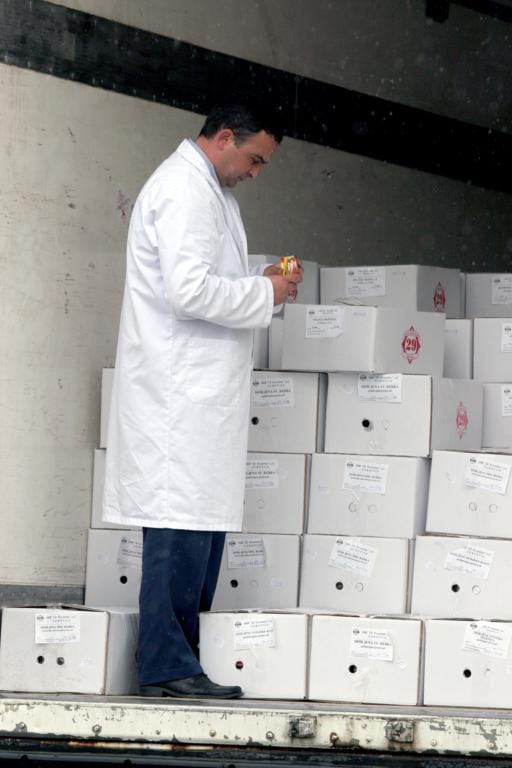

Veterinary inspector Ahmet Hadžiabdić from Bihać must rely on little more than his own nose and what he calls ‘children’s toys’ a magnifying glass and a meat thermometer he got at a workshop, to do his job.

Yet he, on the Izačić crossing near Croatia and 20 colleagues working the borders around Bosnia and Herzegovina, are responsible for insuring that some 70,000 metric tons of meat and animal products coming into the counry every year are safe, free of sick animals or contaminated shipments.

Poor equipment is one problem that hampers the inspection system intended to protect BiH’s food supply. Inadequate sampling, disorganized record-keeping, conflicting laws, smuggling, no way to dispose of confiscated goods, and a lack of consumer protection are others.

What this all means is that nobody can guarantee that the food Bosnians put into their mouths is safe.

Food safety and food importing have been overlooked in the press because of more dramatic problems like refugees and ethnic conflict, warn experts in the field, but it is vital to the country’s well-being.

William Graham, director of Partners for Development Foundation (PDF) a non-governmental organization working with the State Veterinary Office (SVO) to strengthen border offices, said: ‘This program is essential for the development of trade, consumer health and for European Union assession.’

Animal diseases, bacteria in foods, and chemical contamination are all risks to people, according to the World Health Organization’s Food Safety Division.

Wide open borders

When Hadžiabdić opens the door of a refrigerator truck or a tractor trailer, he relies on the color of the meat inside and how it smells to tell him whether he should order the shipment returned to the country it came from.

He checks the expiration date on several items from the back of the trailer. He cannot make it to the front of the trailer because it is loaded in a way that leaves no space to crawl in. And he doesn’t have enough time anyway. He can only hope the merchandise he can’t get to is safe to consume.

BiH stretches its inspectors and scanty resources too thin, some experts say.

The State Border Service says there are 89 border crossings, six of which are designated for transport of livestock and animal products into and out of Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro. Another four crossings are designated for non-meat food products. Before SVO took over the border offices in 2004, the two entities operated 16 crossings, so there has been an improvement.

But Slovenia, in contrast, reduced 25 crossings to just six when it got into the EU.

Len Woods, a senior expert working in BiH on an EU project to implement technical regulations required for accession, lists inspection problems as a key barrier to assuring food safety in the country. Other problems are a lack of food testing stations at the border, political interference, as is always common in BiH, and a lack of money dedicated to solving the problems, he said.BiH inspectors work in rooms that are about the size of the kitchens in the offices of their counterparts along EU country borders. Magnifying glasses and an occassional refrigerator aside, veterinary inspectors around BiH have litte else, including phone lines. Some have obsolete computers but they are never linked to a central office. The inspectors handle documents manually and file them in cardboard boxes – a cumbersome system that makes it nearly impossible to track entrance and exit cargos.’If we could go on the Internet and talk with our peers, exchange pieces of information…if they could announce the shipments to me, that would be very good’ said Hadžiabdić.

Len Woods, a senior expert working in BiH on an EU project to implement technical regulations required for accession, lists inspection problems as a key barrier to assuring food safety in the country. Other problems are a lack of food testing stations at the border, political interference, as is always common in BiH, and a lack of money dedicated to solving the problems, he said.BiH inspectors work in rooms that are about the size of the kitchens in the offices of their counterparts along EU country borders. Magnifying glasses and an occassional refrigerator aside, veterinary inspectors around BiH have litte else, including phone lines. Some have obsolete computers but they are never linked to a central office. The inspectors handle documents manually and file them in cardboard boxes – a cumbersome system that makes it nearly impossible to track entrance and exit cargos.’If we could go on the Internet and talk with our peers, exchange pieces of information…if they could announce the shipments to me, that would be very good’ said Hadžiabdić.

Inspectors at EU entrances, on the other hand, are all tied into a European-wide animal tracking system called TRACES, which is designed to control animal diseases. They know at every moment which animals are entering the EU and where they are destined to end up. Slovenian veterinary inspector Simeon Žilevski at the border crossing at Obrežje said non-EU countries, including Turkey, also use TRACES.’When we enter data into TRACES that we have accepted a shipment, we put in the shop of destination and the region where the shop is located. That information will be picked up by a regional veterinary office’ said Žilevski. The Slovenians learned the system from the Italians.Flawed inspection proceduresAccording to BiH law, food shipments coming over the border must be checked by as many as four different kinds of inspectors.And because the law does not precisely define job responsibilities, veterinary inspectors, as an example, may also end up inspecting confections, drugs and food items containing milk powder. They look at goods on the way out of the country as well as those coming in, which their EU counterparts don’t bother with.The Croatian veterinary inspectors look only at meat, dairy, and other animal products including honey, which makes for faster border procedures.Republika Srpska veterinary inspector Čedo Borić, who used to work at border crossings, believes multi-checks are a waste. ‘That becomes unnecessary bureaucracy’ he said.Despite the layers of inspecting, BiH officials rely on importers to put the health of consumers ahead of financial considerations.’We have to trust the accompanying documents’ said Hadžiabdić.Inspectors admit that trucks can carry in food that isn’t listed in paperwork or that doesn’t belong in a shipment.

Asked about shipments coming from major companies such as Lura or Podravka, Hadižiabdić said that he can inspect those type of importers with ‘closed eyes.’Bogoljub Antonić, the head of the Department for Hygiene and Health Ecology at the RS Public Health Institute, said that according to his data, border inspectors are sending samples from every tenth tractor trailer crossing the border, and that is not enough.It was this inspection system that in February and March allowed four separate shipments of 560,000 cans of Eva sardines marked with bogus expiration dates to enter BiH from Croatia at the border crossing at Gorica, then through the customs office at Grude.Market inspectors discovered the cans during a random check last March of a Podravka warehouse in Sarajevo. Criminal and civil charges are being considered and state officials have assured that no one who may have eaten the fish will be harmed. Still, the errors made at the border still seem glaring.

‘I don’t know if it was negligence or carelessness’ said Zdravko Milicevic, chief market inspector in the RS. ‘I don’t know what it was. But such merchandise shouldn’t have come to BiH.’“Omissions do occur,“ SVO Director Jozo Bagaric said. ‘The fact of the matter is that the (Eva) shipment seems to have come in undetected and was not inspected sufficiently.’Miodrag Lacić, director of Adria, whose Eva fish is distributed by Podravka, said the fish was intended for Croatia, not BiH.The firm, he said, had permission from Croatia only to put new stickers on old cans and to sell the fish on the market. That should have been caught by BiH inspectors. They also should have noticed that the stickers were blank and did not contain information the Croatia officials required on them.Ivica Blažeković, a driver working for Croatian dairy producer Vindija, said inspectors in BiH are good because they don’t delay drivers for a long time and don’t inspect as much as the Slovenians, who often unload a whole shipment and put it in a freezer until they receive the results of analysis.Looking and sniffingAt the end of 2005, SVO completed a manual on border crossing procedures with guidelines as to what equipment should be used and how veterinary inspectors should do their job. However, inspectors didn’t get more resources to help them with those jobs.For example, the manual specifies that all inspectors should have computers, telephones, fax machines, document storage areas and archives, space to unload shipments, a testing room for sampling, and refrigerators. They should also have a saw, knives, can openers, food sample containers, seals, labels, thermometers, scales, a microwave, and other equipment for melting large frozen pieces of meat.If BiH is to enter the EU, it will have to match food control standards for EU border crossings. At the moment, BiH is far from that. During visits to some BiH border crossings, reporters for the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) watched inspectors use the scant equipment they had on hand. Mostly they looked and sniffed.

Rade Dragijević at the Rača crossing said that he sends food samples to Bijeljina for analysis. There could be no testing at the border even if he was trained for it. ‘You would need freezers able to cool down to 4 degrees and deep freeze chambers’ said Dragijević.Hadžiabdić at the Izačić crossing said he doesn’t take samples because there’s no way to transport them to a lab. That didn’t stop him from taking a package of Argeta pate tins after finishing the inspection of a truck.’So that I didn’t climb up for nothing’ he said. ‘Maybe I’ll send it to analysis, and maybe I’m just hungry, so I’ll eat it.’Former Chief RS veterinary inspector Zoran Đerić, now deputy director of the BiH Food Safety Agency, said he finds it strange that inspectors don’t have equipment since inspection does brings in revenue.Inspector Žaklina Radman at the Kamenski border crossing said that inspection of a shipment under 10 tons costs 20 KM, with every additional ton costing 3 KM. Fresh meat inspections under 10 tons cost 30 KM, with additional ton costing 5 KM.State auditors complained about SVO accounting that makes it difficult to trace how much money comes into the state treasury from the agency. The Ministry of Finance said 965,000 KM came in during 2005 from border inpections.

Graham said that his organization donated some computers in late 2005 and is ready to supply more equipment to build modern inspection stations that will meet European standards. But, he said, he has asked first to see a master plan and a strategy for insuring that inspection stations are coordinating with other agencies.Bagaric of the SVO said ‘We don’t want anybody ordering us how to spend money.’ He said he’d only received 8,300 KM worth of equipment from PFD.CIN reporters saw no computers in use during repeated visits to some border crossings.Žilevski at the Obrežje border crossing in Slovenia said the EU requires border crossings to be fully equipped with state-of-the-art computers and laboratories. The EU and the host country share the costs. Woods has suggested that in the short term, BiH could contract with other countries to do lab sampling.Back at the Kamenski crossing, Radman said that two years ago she pleaded with the SVO to get a decent chair. She is still waiting for it.