The East Sarajevo public health clinic was upgraded by Marvel, a local firm owned by Savo Lalović, who is also a councilor on the ticket of the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) for the municipality that provided the bulk of financing for the project.

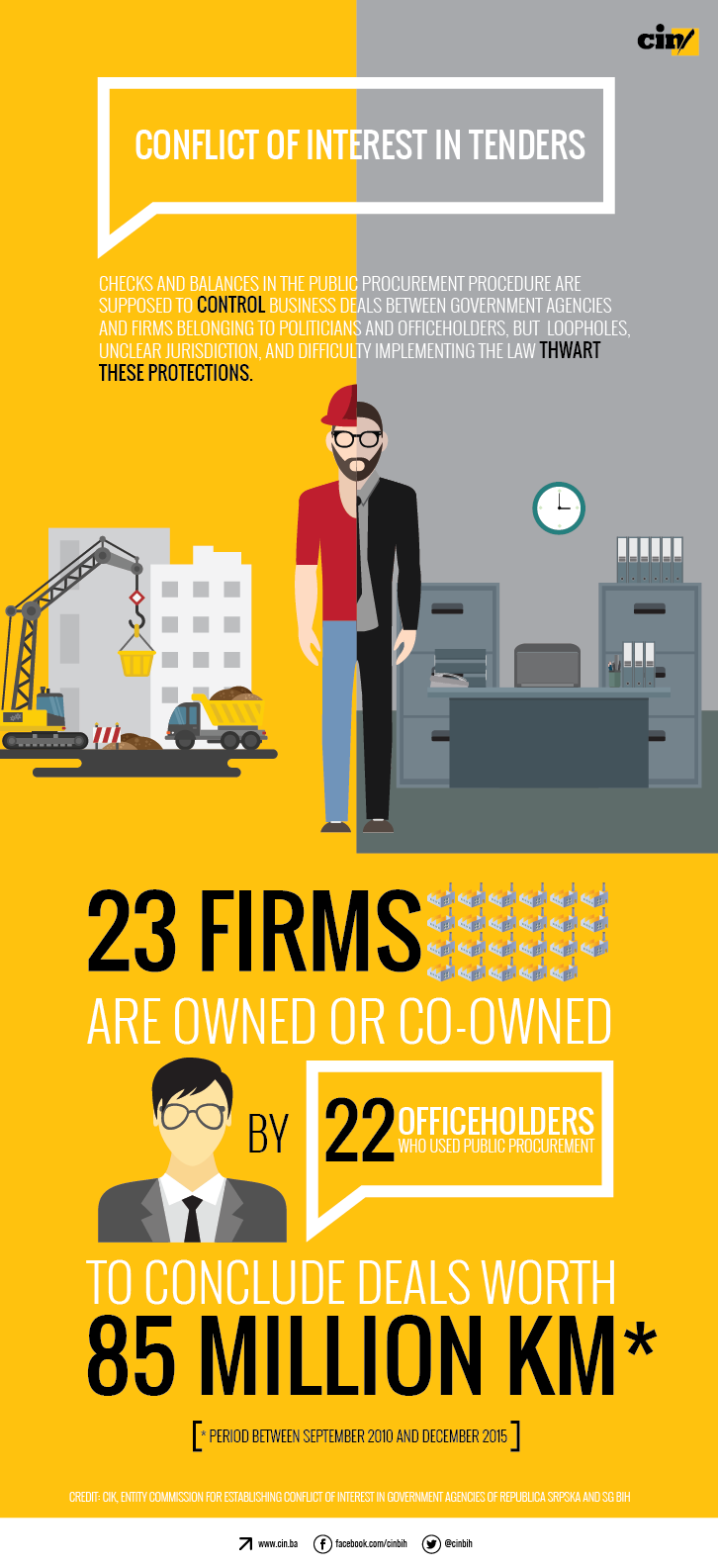

An investigation by the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) shows that he is one of 22 current or former officeholders in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) with firms vying for public contracts in goods, services and works. Firms they fully or partially own have signed at least 85 million KM worth of contracts over a five-year period.

These type of business deals should have been scrutinized under conflict of interest legislation, but it does not because of loopholes, unclear jurisdiction, and difficulty implementing the law.

Republika Srpska (RS) officeholders involved in conflicts of interest and exposed come out unscathed. Most officeholders at other levels of governance – the state, Federation of BiH entity, and Brčko District — have not been probed at all during the past 2.5 years.

Transfer of Authority from Father to Daughter

Lalović’s firm Marvel has concluded 5.4 million KM worth of public works contracts over a five-year period, according to the government newspaper. This included the clinic overhaul that cost nearly 456,000 KM.

Most of the investment for the construction came from the municipality in which Lalović was a counselor. At the end of 2014 and the beginning of 2015, he signed contracts with the head of the municipality, Ljubiša Ćosić, a party colleague of his.

Ćosić told CIN that the fact Lalović’s firm offered the lowest price for the work was paramount. Still, he admitted that he sometimes tipped his party colleagues about planned tenders and their value.

“I tell my party colleagues – it’s no big deal: ‘Look, the municipality will put out a call for applications. The value of the project is 150,000 KM. We have 130 in the budget and we will cap it at 130 because the budget limits us.’ And I told him ‘Well, if you have interest, give it a try.’ And he applied.”

The lowest price is usually the deciding factor, he said, but it might happen that his party peer does not offer the lowest price.

This way of doing business contradicts the Law on Preventing Conflict of Interest in RS Institutions which prohibits officeholders, for a period of a term plus three months after, to manage companies that bid for public procurement work worth at least 30,000 KM.

Lalović concluded contracts worth 13 times more than that and reporter Kosta Petrušić complained to the RS Commission on Conflict of Interest.

In mid-2015, the commission opened an investigation that lasted three months – by which time Lalović transferred his ownership and officer powers to his daughter. The Commission said that Lalović had in this way precluded a conflict of interest and the law was satisfied.

Petrušić said that he appealed the decision, but lost. “I realized that I was chasing wind. Those stupid explanations hurt my common sense.”

Lalović told CIN the ownership transfer was not just a formality. “If tomorrow I hurt my daughter, she can say – you don’t have a say anymore.”

There is no Conflict when Private Interest is Concerned

The Commission has issued similar decisions about the lack of any conflict after investigating business dealings of firms owned or co-owned by at least four legislators and town councilors.

Some legislators are safe as long as they don’t manage their firms: Prijedor-based Bisprom, owned by Miladin Stanić from the Serb Democratic Party; Oktan Promet in Bijeljina owned by Vojina Mitrovića from SNSD; Zvornik-based Obuća owned by Vladimir Mijatović from the Socialist Party; and RDS PROM from Mostar, co-owned by Ramiz Šemić from the Party for Democratic Action (SDA).

The RDS PROM’s contract was more than half that total. A co-owner Šemić told CIN that he’s a legislator with the East Mostar Municipal Council, while his wife founded the company. He said that his office and political affiliation were not relevant to the company’s success.

“I wish I had connections so that I did not have to work and get up every morning at 3 a.m”, he said.

Commission’s president Obrenka Slijepčević said the law does not prohibit officeholders from being founders, owners or co-owners of private companies. What is controversial is if officeholders vote to give a contract to a firm they are connected to.

Since public procurement contracts are usually inspected by the government agency’s commission which puts out a specific tender — not by legislators or councilors — it is not hard for officeholders to bring a written statement that shows how they did not vote to give a contract to their firm.

Over the past six years, the Commission has found at least five officeholders involved in conflicts. Most solved the problem similarly to Lalović, or appealed in court and thus bought time to stay in office until the end of their terms.

A non-governmental organization Transparency International BiH is advocating changes in the law that could lead to sanctions and voiding of contracts blemished by conflict of interest. The organization’s Ivana Korajlić says that such legal provisions exist in other countries.

Blockade of the System

For officeholders at work in state, Federation and Brčko District institutions, stricter laws had been put in place and overseen by the Central Election Commission until November 2013. According to these laws, the value of contracts between private companies and institutions financed from the budget could not go over 5,000 KM and companies owned by officeholders were banned from participating.

Between 2008 and the end of 2013, the election commission sanctioned at least 52 officeholders, charging several thousands KM fines and/or banning them for running for office for a term because of illicit business deals.

After this the law on the conflict of interest in the BiH government agencies was amended, and CIK lost its regulatory oversight over all levels of governance.

These changes led to the setting up of the Commission for Establishing of Conflict of Interest with nine members: six state MPs and three managers of the State Agency for the Prevention of Corruption and Coordination of the Fight against Corruption. The group has yet to issue a decision on the conflict of interest due to internal disagreements.

A former commission president Halid Genjac said that two votes from each of the three constitutive peoples are needed to launch a probe into conflict of interest or to issue a decision. “If two do not raise hands, an obvious conflict of interest will not be the conflict and there would be no proceedings.”

The amendment that ended CIK involvement did not change the law itself, said the head of the Office of the Commission Danka Polovina-Mandić. There just is no body to enforce it any longer.

Officeholders from Brčko District are in a similar situation. Following the amendments, the oversight powers were bestowed on Brčko District Election Commission in the beginning of last year. However, commission’s member Milan Tomić said that they had not looked at any case of conflict of interest, because those powers were not given to them by the Election Law according to which they operate. “As if someone had intentionally created a law that cannot be implemented, i.e. has no benefit or investigation of those who potentially are in the conflict of interest,” said Tomić.

He said that there has to be consensus among all seven members of the Election Commission in order to launch a probe in Brčko.

This could be a problem in case they receive a complaint to look into a possible conflict of interest for the chairman of the District’s Assembly, Đorđa Kojić. He’s an SNSD member and Tomić’s party peer. In that event, Tomić could be exempted from voting.

Over a five-year period, Kojić’s firms Brčko Gas and Brčko-Gas Insurance have concluded contracts worth nearly 4 million KM. His firms are supplying and servicing cars, fuel and insurance. At least three contracts have been concluded with agencies headed by Kojić’s party peers.

An anonymous complaint was filed with the RS Commission for Establishing Conflict of Interest when Kojić was an RS MP. The commission decided there was no conflict of interest because Kojić filed a statement saying that he only owned his companies, and was not an employee or an officer. He also put in writing that “Whenever the National Assembly has insurance laws on its agenda, I duly register for it, but leave the assembly premises before the show of hands. This means that I have never voted.”

Beside such loopholes, current laws do not consider the managers of public companies, while former officeholders are only partially covered. Korajlić thinks this should be changed, “because when you leave an institution and the office, you still have contacts and you still have inside information that you can later use for a private firm.”