Sarajevo University President Hasan Muratović set off a panic among students and professors a year ago when he mandated major curriculum changes to bring the school in alignment with reforms changing universities across Europe.

He acknowledged he was pushing for immediate and radical change, and he chided the university senate for resistance. Why, he asked, was Bosnia and Herzegovina still standing still when colleagues elsewhere were busy upgrading their schools and integrating into one European system?

‘I find that we were objectively not ready for that step’ claims Milenko Blesić, professor at Sarajevo Agricultural faculty. ‘The first reaction at the faculty was where is the law?’ he said.

Nevertheless, Blesić and a group of colleagues plunged into the Bologna Process, as the reforms are known. They worked throughout the summer and by the time fall classes began had written thousands of pages of new curriculum.

Educational experts say it is time for all BiH schools to do the same. However, two years after the country signed on to overhaul the higher education system, many ministers, deans and professors cannot even explain what Bologna is or what it is supposed to do.

Among 40 countries that had committed to higher educational improvement last year, BiH ranked dead last with Andorra and Serbia and Montenegro in making changes. Since then, five new countries have joined the Bologna movement.

What is the Bologna Process?

Europe is trying to harmonize dozens of university systems of varying quality and tradition across the continent. By doing so, educators hope to fire up European economies by turning out world-class graduates who will better compete against the graduates of universities in the United States and emerging Asian nations like China.

The Bologna Process changes schools in major ways. It requires accreditation – or formal ratings – that insure schools meet quality measures. It requires that all universities offer graduate as well as lower-level undergraduate courses. They must participate in a credit-transfer system that allows students to get credit for courses at their university no matter where in Europe they took them. In poorer countries like BiH bringing their schools up to one high European standard means modernizing facilities, teaching methods and the very way universities and departments are organized.

‘This is all about the creation of a single labor market where, for example, an engineer educated in Portugal could move to Sweden if there was a need for him’ explains Professor Lamija Tanović, a BiH representative on the Bologna Follow-up group, which keeps track of how well the country is applying reforms.

An examination by the Center for Investigative Reporting shows that Bosnia-Herzegovina is failing in its implementation of the Bologna agreement and its university system is failing its students and the country’s economy.

Needed first: a unified BiH system of education

Tanović said BiH falls far below the standards of most European higher education in large part because nothing has been done at the state level to unify and standardize university education.

The idea of integrating into a larger European system of education is laughable, she pointed out, when the higher education system within BiH itself is not integrated.

As Nedim Vrabac, an official with the education department of the Council of Europe, put it, ‘In a systematic sense there is no Bologna in BiH.’

Fuada Stanković, former president of the University of Novi Sad now working for the European University Association, said that university education suffers in both Serbia-Montenegro and in BiH because those countries lack state law on the topic. Without that basic start, she said, initiatives to improve schools have lagged. Since she spoke, Serbia has passed a law.

Especially after a decade of war in the mid 1990s followed by emigration of many scholars and researchers, BiH universities have stagnated.

Dragan Mikerević, a former premier of the Republika Srpska and a professor at the Banja Luka School of Economics, said science and technological research is at a standstill in the country.

‘In the 2003 budget I found 0 KM allocated for research’ he said. ‘We have no institutions willing to invest in science. How can we meet the Bologna (commitments)? We’re not organized. We have to reform the institutions.’

Among additional problems, drop out rates are high in BiH schools and few students graduate in the usual four years. Professors are so underpaid they are not motivated to try new teaching methods and they moonlight. Students are so uninvolved in governing the schools they attend they silently accept the giving and taking of bribes for grades.

Passing a state law on higher education

Seven of the 62 members of parliament are university professors as are many top ministers. But the government has bogged down since 2004 in trying to pass a unifying higher education law that could help fix much of this. The trick has been finding a bill agreeable to both entities and to all ethnic groups.

The failure so far has cost BiH a $1.5 million loan from the World Bank offered contingent on passage of a law in accordance with Bologna principles. Another offer from the bank for a $24 million loan with the same condition is in jeopardy.

Croat representatives defeated the first efforts at passing a law. They claimed it violated their right to use of Croatian language in their schools. The state Constitutional Court upheld that claim and the law was altered and sent back. This time RS representatives stopped passage, worried about taking away the entities’ right to regulate education.

A nationwide poll of 1,500 residents prepared in January for the OSCE Mission in BiH showed a deep divide between Bosniaks and Serbs on the question of whether a state-level Ministry of Education is needed to guarantee the same standards throughout the country. Ninety-four percent of Bosniaks supported such a centralized ministry but only 40 percent of Serbs felt the same.

The same poll, which did not differentiate between secondary and higher education, also showed division on the question of languages. Fifty-one percent of the Croat respondents said they find it acceptable that the language of instruction used in classrooms prevents children from going to classes together. Only 20 percent of Bosniaks and 26 percent of Serbs felt the same.

The Bologna efforts are one of the many reform attempts that have been hijacked by the continuing political disagreements between nationalist political parties say international and local experts.

‘HDZ’s propaganda did a very good job, so SDS and SDA had no need to do much’ Claude Kieffer, deputy director of the Education Department of the OSCE, said about the first defeat of the law.

He admits that the international community has neglected higher education, which should have been a major focus right after Dayton. Now instead, he said, a generation of students have gone through schools getting ‘totally twisted views on culture, ethnic communities and minorities, because the system, as it is now, supports prejudice against others.’

He said that the government seems incapable of creating a system, which respects the rights of all ethnic groups and that such a system cannot be imposed by others.

At stake is the political control of the people, Kieffer said.

‘If I were to be cynical, any clever politician, if he wants to stay in control would make sure what pupils are taught propagates party ideology. It basically makes it difficult for people to think for themselves’ Kieffer said. ‘It is potentially dangerous to teach people to think for themselves.’

A newly revamped version of the higher education bill has not yet been sent to Parliament.

In the absence of a single state ministry enforcing law about universities, the entities and cantons set up by the Dayton Accords that ended the war have stepped in. A total of 13 ministries have a say over what happens in universities.

Even within individual universities, faculties rather than a central administration hold money and decision-making power.

‘Universities in BiH are very much decentralized’ said Stanković, in contrast to the usual European model. Making change, improving budgeting and keeping track of student and professor data all become complex and difficult to manage when you have many people in charge. Changing this system, a remnant of the old Yugoslavia socialism, will be difficult.

‘You know, when somebody wields power, he or she is not going to relent’ Stanković said. ‘And departments are legal entities and if they have some money, if they get money from the government, they start behaving like bosses.’

The state-level Ministry of Civil Affairs has the vague assignment of coordinating entity-level educational activities and representing BiH in international educational matters. However, Esma Hadžagić, deputy minister, admits that control over universities nationwide is uneven and disorganized. One cantonal minister, she said, is under no obligation to co-ordinate with other cantons, entities or the state.

She said it is sometimes impossible even for the FBiH Ministry of Education to coordinate 10 cantonal ministries.

‘The FBIH minister has to write to them, to plead with them to answer his call and the response comes from only three of the ministers’ said Hadžagić. ‘Then again I have to co-ordinate everything at the state level of Ministry of Civil Affairs. That is nonsense.’

Vrabac, with the Council of Europe, said that while the structure of the educational system here impedes reforms, some changes could be made even without a new system or without a state law.

Tanović agrees that schools themselves could divide work into undergraduate and post graduate study.

The European University Association (EUA) in a report on progress on Bologna urged professors to stop waiting for politicians.

‘Universities have to start dealing with this issues immediately, on their own and together, without waiting for the passage of the respective laws’ the report reads.

It suggests that schools should – as the University of Sarajevo did hastily last summer – restructure existing courses and degrees and begin using credit-transfer.

European experts found that the voluminous curriculum of BiH classes compounded with outmoded oral examinations still required here result in years of prolonged study. It takes the typical BiH student eight years to graduate instead of four and frustration contributes to a high drop out rate.

Experts have recommended that universities replace oral exams with written tests and grade students objectively on work they do throughout a course.

Stanković said she and EUA colleagues, also concluded that universities here badly need better teaching that encourages students to discuss, interact and solve problems.

Right now students sit though long lectures passively taking notes or they don’t go to class at all. They pass solely on the basis of an oral test.

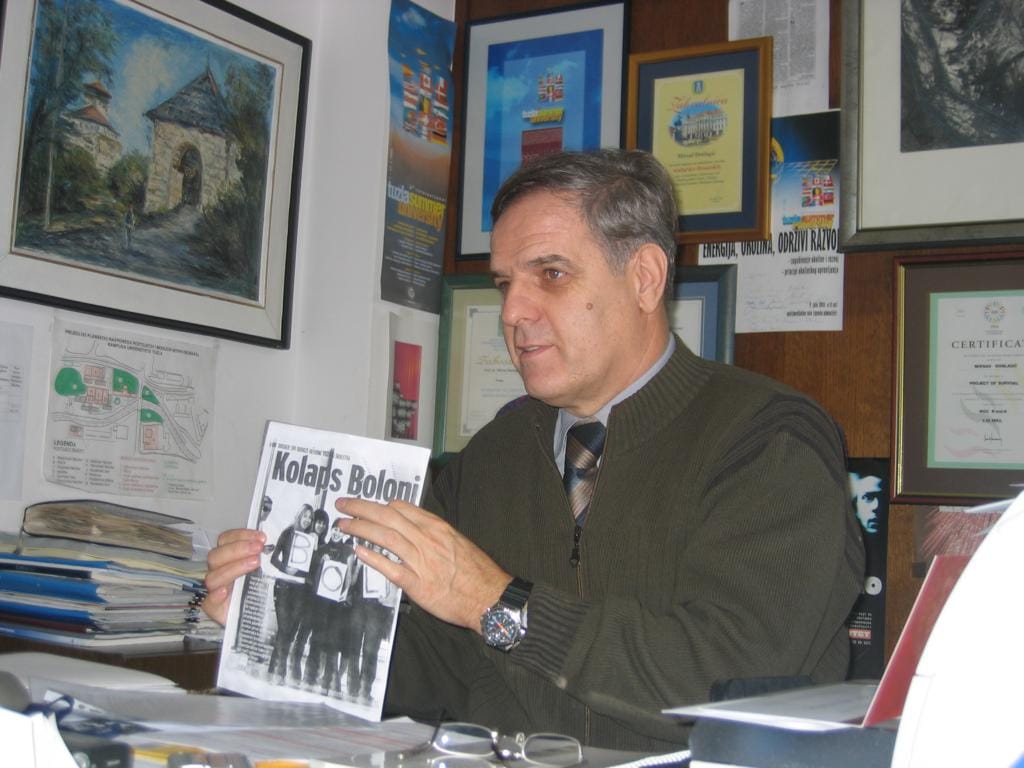

‘Bologna is turning a student into a working man’ says Džemo Tufekčić, interim president of the University of Tuzla. The reforms push hands-on laboratories, seminars and independent work done as homework.

The role of the professor also changes with Bologna, he said. He ‘steps down from his stand and takes a role of facilitator.’

Accreditation could be trouble for some schools

Just as BiH has been unable to agree on one law about universities, officials have been unable to reach consensus on a national accreditation agency. The Bologna Process requires a governing body that sets standards and holds institutions to them.

Such an agency could substantially change universities here if BiH were to have the same experience with accreditation as Croatia.

Marko Tadić, a professor at the School of Veterinary Medicine in Zagreb, said that faculty was reworked ‘from scratch’ in order to meet standards. Computers and new equipment were bought, desks were moved, and classes were changed.

Once BiH set up an accreditation system, universities would get three or four years to upgrade to new personnel and premise requirements.

That could be hard for some schools, especially small and poor ones.

‘Poor universities like this one in Bihać and East Sarajevo will get into problems’ Blesić predicted. ‘It will be impossible to get accreditation if the university doesn’t have 60 percent of its professors permanently employed.’

Tanović said requirements for scientific laboratories may also be difficult to meet.

‘I can’t imagine what would happen’ she said about future accreditation teams, ‘if they take a look into our faculties and if they see what we actually have.’

The state has also failed to establish an information center that would decide on the form and content of diplomas issued by accredited universities. The center would provide information about BiH schools outside the country and could validate diplomas issued in other countries.

Major employers in BiH explained in a recent focus group study by Prism Research conducted for CIN that they are reluctant to hire students who have studied abroad or at private university because of just this reason – they have no guarantees their degrees are any good.

Tanović said BiH students trying to get credit for courses taken outside BiH – or vice versa – are likely to find their plans blocked. That in turn discourages Bosnians trained abroad from finishing school at home or even coming back at all.

‘When I showed in Italy my BiH certificate they turned me down, but they did recognize the Slovenian one’ said Nusret Muharemović, a 25-year-old student in the Tuzla Department of Mechanical Engineering doing a masters course in Slovenia. ‘We are always looked upon by the West as less competent.’

He intends to return to BiH when he’s gotten his degree. But Tufekčić said he can name nine assistant professors who have gone abroad for doctoral programs not offered in BiH and never returned.

Tufekčić said he sees BiH as politically unwilling to pay for reforms that could reverse this.

‘Frankly, we’re a burden to this society, that is to the political society’ he said, ‘because they are always struggling to set aside money in the budget, instead of setting up a fund for research and development.’

Mirsad Đonlagić, vice-president for inter-university cooperation, said that the state has not allocated anything for turning the Bologna recommendations into reality. In contrast Croatia sets aside 17 million KM for change.

Božidar Matić president of BiH Academy of Arts and Sciences said that the country doesn’t perceive higher educational reform as an investment.

‘Every reform is investment’ said the president. ‘They call for a reform but nobody said who is supposed to be the financier and how the reform can be implemented and how much will it cost.’

Experts contend that most students and professors don’t understand clearly what Bologna is all about so their support for it is weak, not surprisingly.

Administrators and professors have received no training and the state has conducted no publicity or awareness campaign on what the reforms could mean for the country.

Even in schools that have made changes on their own, Tanović said, many professors feel unprepared. They don’t know how to grade student portfolios, for example, or how to conduct seminars in which students give presentations and talk instead of professors.

Amra Muslić, the 22-year-old president of the Association of Students in Zenica and a senior studying English language and literature, said that both students and professors have no idea how to go about this new process.

Some schools have embraced reforms

Officials at the University of West Mostar admit that they need more professors to upgrade teaching, but some other improvements have begun, according professor Slavo Kukić of the School of Economics.

‘We have already started a distance education classroom, video conference and three computerized classrooms. We already have all the technology needed for modern education’ he said.

The most impressive gains in reaching the goals of the Bologna Process have been at the University of Tuzla over the past five years under President Izudin Kapetanović, who has been praised by international education experts for his efforts.

Mirjana Radić, university vice-president for financial affairs, said departments have yielded power to a university-wide administration that deals with salaries and hiring. Courses have been reformatted so that students now take the same 30 credits a semester that students throughout Europe do. Five teams at the school monitor and do follow-up to keep track of the reforms. The school last year hired some 100 new young employees needed for the smaller, hands-on classes that the Bologna Process demands. Finally, a diploma supplement adopted by the school is meant to help students study at other universities in Europe without bureaucratic hitches.

This month, however, Kapetanović lost a court bid to serve another term in the presidency, throwing the future of the reforms he championed into uncertainty. Professor Edin Delić, head of the professors union at the school, is openly criticizing Kapetanović’s reform efforts saying he made many mistakes and went beyond integrating the university. He built a rigid politburo, Delić said.

Tufekčić said the next months and years will be critical as the school finds an acting director and replacement for Kapetanović. The new person, he said, ‘must plunge into the reforms with the same pace and continue implementing all aspects of the Bologna declaration.’

As Muratović’s announcement heralded, Sarajevo University, the largest and oldest in BiH, leaped into reform last year, with officials pushing through a cantonal level law in sync with the guidelines of reform.

‘It was initially a disconcerted effort’ admitted Blesić, ‘but we’ve managed to develop good curriculums and syllabuses.’

The changes can be seen in the classes this semester of Mirha Bičo Ćar, one of five assistant teachers in economics of enterprise.

There used to be 250 students in that class, she said. Now they are broken into small groups. Students now must participate in discussions, write papers and prepare presentations for which they are marked, not just take an exam. Ćar handed out a syllabus at the start of the semester outlining class activities for the entire semester.

It’s all a lot of work, she said, but students appreciate the difference.

President Muratović remains unapologetic about rushing into reform. ‘Incremental change would not have succeeded’ he said, ‘because those opposing reform would have prevailed. There are some in the academic community whom you cannot win over unless you bring in a radical change.’

There is a still a long way to go, Blesić cautioned. ‘Bologna is really about the change of thinking and mind-set on the part of professors and students.’