At the end of 2020, the Bosnian public was shaken by the brutal murder of Jasmina Klico in the Sarajevo’s Municipality of Vogošća. She was shot multiple times and killed by her co-worker, Elvir Hajdarević.

Earlier that year, before the tragic incident, the Sarajevo Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office received multiple police reports about Hajdarević, who had threatened to kill Klico and posed a danger to her safety. The case was assigned to Prosecutor Aida Topalović.

However, the prosecutor did not open an investigation and closed the case. She informed the victim of this decision, but since Klico was murdered in the meantime, the notice of non-investigation was received by her daughter.

In May 2021, the Sarajevo Cantonal Court sentenced Hajdarević to 11 years in prison for the murder of Jasmina Klico. The trial relied on evidence that the police had previously submitted to Prosecutor Topalović.

Due to negligence and lack of diligence in handling the case, the Disciplinary Commission of the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council (HJPC) initiated disciplinary proceedings against Prosecutor Topalović in early 2024. That same year, she was penalized with a 30% salary reduction for six months.

During the proceedings, Topalović argued that her actions were a professional mistake, not a disciplinary offense. She stated that she was handling over 400 cases, was constrained by workload quotas, and had to prioritize cases she considered straightforward and well-documented— this case being one of them. She explained that her decision was based on the case file, which, in her view, lacked sufficient evidence of a criminal offense.

In her defence during the disciplinary proceedings, she stated that the Prosecutor’s Office handles 700–800 cases of endangering safety each year, most of which are closed with an order not to conduct an investigation. She also pointed out that one of her colleagues had made the same decision a few years earlier in a similar case involving Hajdarević, ruling that there was no evidence of a criminal offense.

In its reasoning for the decision against Prosecutor Topalović, the Disciplinary Commission emphasized that judicial officials must prioritize protecting victims, placing human life above procedural norms or past practices. It concluded that Topalović had acted hastily in deciding not to open an investigation and that her actions had undermined the integrity of the Prosecutor’s Office.

The Disciplinary Commission found that Hajdarević was encouraged by the prosecutor’s inaction, which allowed him to continue harassing and threatening the victim—ultimately shooting and killing her with four bullets.

Prosecutor Topalović refused to speak with a journalist from the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIN) about the case. Through the spokesperson of the Sarajevo Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office, she tried to have her disciplinary proceedings omitted from the article, saying it was distressing for her.

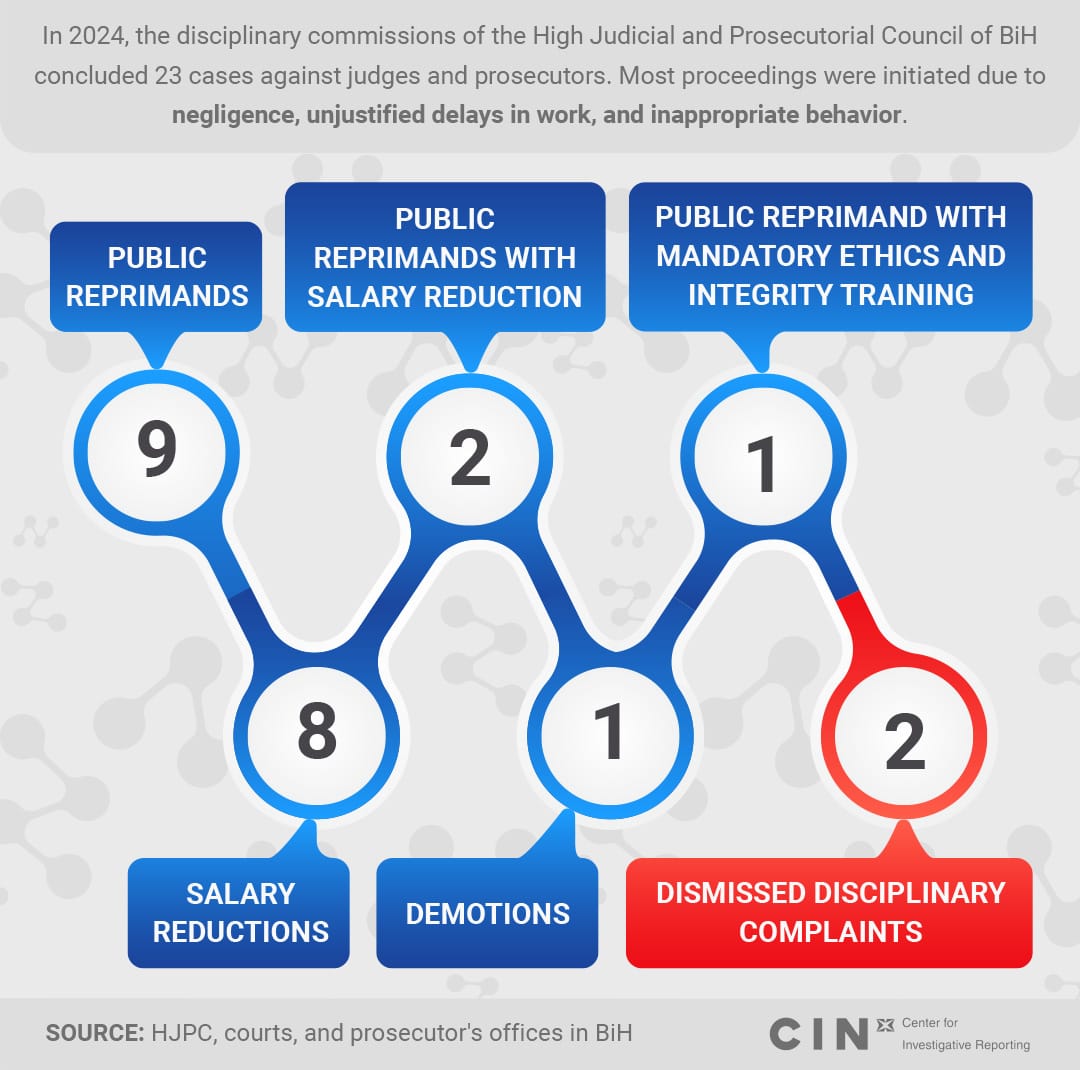

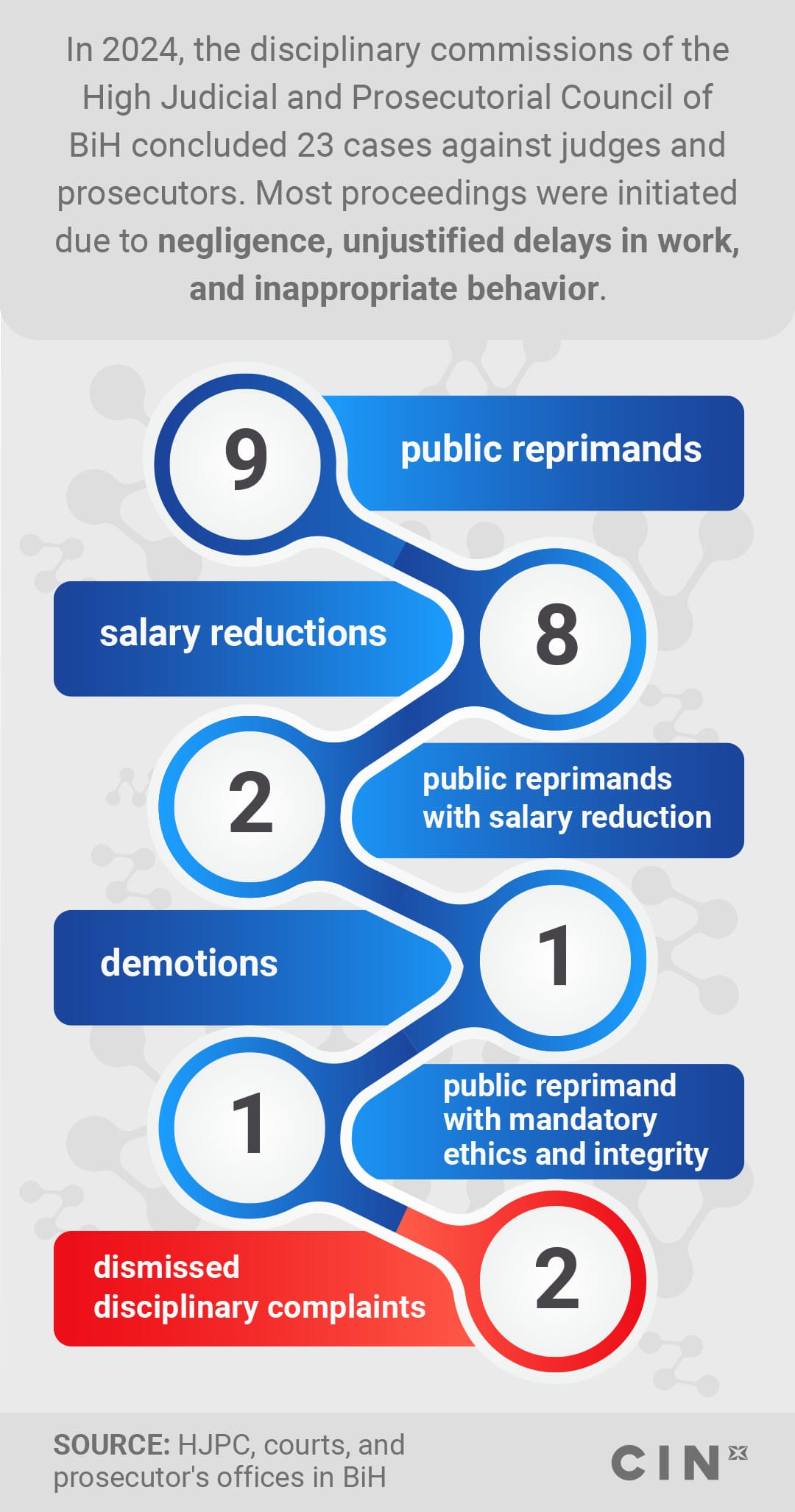

Topalović is one of 23 prosecutors and judges who faced disciplinary action in 2024. Most cases involved negligence, unjustified delays, or inappropriate conduct.

Nine received public reprimands, while eight had their salaries reduced by 5% to 50% for periods ranging from three to twelve months. Two were penalized with both a public reprimand and a salary reduction, while one prosecutor was required to attend ethics training in addition to receiving a public reprimand. A deputy chief prosecutor was demoted to a prosecutor, and disciplinary charges against two judges were dismissed.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s criminal codes do not classify femicide as a distinct offense or a specific form of violence against women. Instead, such crimes are prosecuted under legal provisions for murder and hate crimes based on gender identity.

In response to a series of gender-based violence and femicide cases over the past two years, the House of Representatives of the Federation Parliament passed the Domestic and Gender-Based Violence Act in early February 2025. The Act aims to strengthen protections against domestic violence and prevent violence against women.

The proposed Act introduces urgent protection measures enforced by law enforcement, establishes victims’ rights, and safeguards children affected by violence. It also ensures that prison sentences for violating protection measures cannot be replaced with fines.

The Act grants greater authority to law enforcement, allowing them to temporarily detain perpetrators of violence. It also introduces the possibility of electronic surveillance for individuals subject to restraining orders, enabling the police to track compliance and intervene promptly if a violation occurs. For the Act to take effect, it must also be approved by the House of Peoples of the Federation Parliament.

Disciplinary Reoffenders

One-third of the judges and prosecutors sanctioned last year were re-offenders in disciplinary violations. Among them is Adis Berbić, a prosecutor at the Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office of Zenica-Doboj Canton, who faced disciplinary proceedings for the third time.

In his most recent case, Berbić was disciplined for failing to take any action in 82 cases or for acting only after prolonged periods of inactivity—lasting one, two, or even three years. One of these cases involved child abuse in Visoko, where, despite being notified by the police, he failed to visit the crime scene, a duty he was obligated to fulfill.

As a result, some cases were closed without an investigation, while most were reassigned to his colleagues.

Berbić admitted his guilt, claiming he had been ill. The disciplinary counsel sought his dismissal, arguing that previous sanctions—two salary reductions of 10% for four and five months, respectively—had failed to produce any effect. Despite these penalties, Berbić continued to neglect his cases, forcing other prosecutors to take over his workload.

The Disciplinary Commission denied the prosecutor’s request, explaining that dismissal is the harshest penalty, reserved for cases where a judge or prosecutor is deemed unfit for their role—which they did not believe applied to Berbić. Instead, he was penalized with a 50% salary reduction for one year and a public reprimand. The Commission concluded that these combined sanctions would be sufficient to deter future misconduct. Journalists were unable to reach Berbić for comment, as he was on sick leave.

Last year, two disciplinary complaints against judges for delays and negligence were dismissed.

One of the judges, Lejla Numanović of the Municipal Court in Gradačac, drew significant public attention in the summer of 2023 when she rejected a police request for a restraining order against Nermin Sulejmanović, which would have barred him from approaching, harassing, or stalking his common-law wife, Nizama Hećimović.

After receiving the court decision, Sulejmanović killed his wife and then himself.

Judge Numanović was not held accountable for rejecting the police request, as judges cannot be disciplined for their legal opinions or decisions made in the course of their official duties. Instead, the disciplinary complaint against her alleged that she had made an error when drafting the ruling. She had copied a previously issued decision, mistakenly including information unrelated to the case at hand.

The disciplinary complaint against Judge Numanović was dismissed. The HJPC commission ruled that copying legal provisions is standard practice and not an error. While the judge did make a technical mistake, the commission determined that it did not create a legal issue, as she corrected it before the ruling was officially issued.

Judge Numanović declined to comment on the proceedings.

According to the HJPC’s Rules of Procedure, disciplinary proceedings serve as a barrier to the promotion of judges and prosecutors. Depending on the severity of the sanction, those who have been disciplined are prohibited from applying for vacant positions. This restriction can last from one to eight years following a final ruling or for the duration of a temporary suspension from office.

Decisions in disciplinary proceedings are published on the HJPC website but they are anonymized, which makes them difficult for the public to interpret. CIN monitors these proceedings and compiles publicly available data in its database “Disciplinary Sanctions against Judges and Prosecutors“.

This database contains records of 308 disciplinary decisions issued between 2010 and the end of 2024, involving judges, prosecutors, and expert associates who were either sanctioned or cleared of responsibility for violating the HJPC Act and ethical codes. It includes their names, the institutions where they worked at the time, descriptions of the offenses, and the final rulings.

By the end of this investigation, journalists had identified 272 judges, prosecutors, and expert associates. Since comprehensive records of disciplinary sanctions are not publicly available elsewhere, this database remains a unique resource.