Slobodan “Mike” Pavlović, the founder of what is now the largest private university in Bosnia-Herzegovina near his home village of Popovi on the Serbian border, is not a professor or a scholar and he has no children.

As a Bosnian Serb immigrant, Pavlović figured out how to make a fortune in Chicago”s wide-open real estate market and then just as the 1990s war was igniting, he came back with a big, bold idea. A flamboyant and controversial businessman who models himself after Microsoft”s Bill Gates and ardently supports Serb unity, he set out to build a whole city.

He has become an educator because Slobomir P University is a key component of his grandiose idea to turn a bleak area near Popovi into Slobomir, a city combining his first name and his wife”s, Miroslava, and connecting BiH with Serbia.

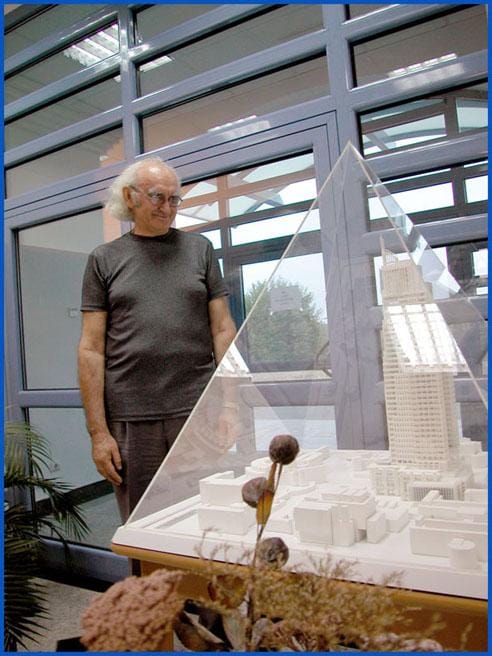

But while the 800-student university will graduate its first class in 2007, the city has not gotten off the ground. Pavlović, who at 68 boasts the build of a man who rises before 6 a.m. for a daily workout, says only God knows if he’ll live to see the bustling Slobomir depicted on his website. That city thrives with 30,000 residents, a sports center, apartments and a skyscraper.

For now, Pavlović revels in the risk and in the adulation his efforts have brought him as a patriot and philanthropist.

He holds a medal of St. Sava from the Serb Orthodox church; The Serb Voluntary Guard gave him a medal too. He emblazons his name and image on his constructions, He readily poses in his long white hair and expensive suits for photographers, the very picture of a do-it-my-way if eccentric executive.

“I believe in myself and my success,” he sums up at the end of the autobiography, “How I Made It,” he wrote in 1999. He says he”s working on volume two.

Pavlović has come a long way from federal custody in Chicago in the mid 1980s.

Dreams of success and Tarzan

Pavlović likes to begin the story of his rise further back than that, though. He starts in Popovi where he shepherded sheep and cattle as a boy. He says he thought then about how someday, he would build a bridge across the wild Drina. He saw it as the same rickety-slat bridge Tarzan built in his movie jungle. He jokes that he succeeded beyond his imagining.

The fourth of seven children, he didn”t have an idyllic boyhood, by his telling. His father was imprisoned in Bijeljina because of anti-Communist leanings. He says his father urged him to leave Yugoslavia, and in the mid-1960s after a stint in the Yugoslav Army, he left for the United States. He writes that he had $40 in his pocket and no English.

But flying over the states, seeing the cars, the buildings, the commerce, he recalls, he said he knew he’d landed in the right place. Here he could succeed.

And he did. In a Chicago factory he found work and another emigrant from Yugoslavia, who said no at first, then relented and married him. He took electrical engineering classes and started a degree in business management, he says, but then discovered the magic of real estate.

It multiplied money, he found.

He wrote in his book and explains to reporters that he took $2,000 of savings, borrowed $10,000 more from his brother, in-laws and others and with that as a down payment borrowed enough from a bank to buy a $60,000 building with six apartments. He fixed it up and six months later sold it for more than twice as much.

The trick he said, was selling it to himself. His firm Hillcrest Real Estate began with this deal. As the owner of a building worth $130,000, he had collateral enough for bankers to loan him enough to pay off his old debts and buy a building with 38 apartments.

Pavlović says he bought multiple buildings, replaced the windows and roofs and raised the rent tenants were charged so that the value of the buildings jumped. And he kept them rather than sell them away.

Pavlović had discovered the pattern of his business career, he says. Borrowing to invest and swapping property up for better are lessons he wants to teach young people in BiH through his university and the banks he now owns. Familiarity with credit and the rapid turn-over of money are the way to higher living standards, he advises in his book.

But nearly two decades of good luck in America for Pavlović came to an end in the 1980s.

Strong as a rock against evil people

Pavlović devotes just a paragraph of his 62-page autobiography to the five years during which, he writes, he “discovered the true depth of human hatred and meanness,” while “defending myself from evil people and unjust charges.”

Asked about that paragraph, he told journalists for the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN), “That was 20 some years ago. I don’t want to talk about it.” He prefers, he said, to look to the future.

Asked about yellowing newspaper clips written of the criminal accusations against him, Pavlović told CIN, “I have never done anything against my conscience. They wanted to destroy me. Everything came out. I was not guilty.”

Asked about court documents, including transcripts of his own testimony, that CIN obtained from archives in Illinois, Pavlović said he would say a “couple of sentences” about how he was victimized by a lawyer and by fellow Serbian emigrants jealous of his success.

He said rivals set him up. In 1982, a task force of federal agents came to him posing as people interested in buying expensive real estate and paying in cash. He said his lawyer arranged to accept millions in cash and deposit it in bank accounts, each containing less than $10,000. Law enforcement officials, he said, called that money laundering.

Asked about a transcript that shows Pavlović testified in a U.S. District Court in 1986 about taking $1.3 million from men he believed were drug dealers for deposit in a Swiss bank account, he said: “You see, my lawyer says, ‘Mike you cannot fight, better to accept.’” I say OK then.”

Pavlović said he was put on probation, didn’t go to jail and never got into trouble again. “I never want to do under the table something,” he said.

Federal charges

John Loftness, chief spokesman for the U.S. Bureau of Prisons’ central region in Kansas City, Mo., said Pavlović was sentenced to six months imprisonment but got two months off for good behavior. He did part of that sentence in the Metropolitan Center in Chicago, the rest in a half-way house in Indianapolis where he was released March 22, 1988.

Loftness said bureau records show that Pavlović pleaded guilty to “giving false testimony to a court or grand jury.” Court records show that this plea and sentence were part of a arrangement Pavlović reached with prosecutors after he was caught up in an undercover federal investigation.

The real estate tycoon and four other men, according to records, was also charged with arson in the deliberate burning of a dilapidated, heavily insured apartment building in Chicago in the winter of 1981. The five told different and conflicting stories in various court proceedings about which of them did what exactly.

The arson was a fumbled affair, as the building owner tried to get his tenants out of the way, the arsonist failed in his first two attempts to torch it, then got caught by several tenants while pouring out gasoline, court records show. Officials decided that Pavlović, who sold the building originally to one of his co-defendants, had arranged the insurance on it and he gave $9,000 to help a co-defendants trying to run away after the arson.

Pavlović agreed to change the testimony he”d given about the arson and to implicate the others. On the witness stand in March 1986, he was questioned about this. “Did you lie?” he was asked.

“I didn’t lie,” Pavlović said. “I didn’t tell truth.”

“Tell me how not telling the truth is not a lie,” he was asked.

“I cannot answer that,” Pavlović said, according to the transcripts.

Court records show that Pavlović and his lawyer were caught in a 1982 “sting operation” in which federal agents posed as drug dealers. Pavlović, according to an indictment, agreed to move $1.3 million in narcotics profit in amounts small enough to escape U.S. government detection into a secret Swiss bank account. The records say he charged a 5 percent fee.

“Yes,” Pavlović said on the witness stand in the 1986 U.S. District Court proceeding, according to the transcript, “we took the money to transfer to Switzerland. That”s true.”

Pavlović and his lawyer also were indicted for working on another laundering deal in 1983 to 1984 with federal agents posing as criminals, records show. This scheme, involved “the use of a diplomat from Yugoslavia to ”match” deposits in U.S. banks with deposits in Yugoslavia.” Agents gave him and others more than $2.2 million, the indictment says. This money was broken into amounts of less than $10,000, deposited through an Indiana bank into a Skopje bank, then wired to a Swiss account, minus a fee.

Pavlović has not been charged with any crimes since this time. Patricia Kelly, a University of Washington business professor who agreed to do work at Slobomir University before she learned of his background, said the school owner told her that he”d gotten mixed up with some bad people and he”d learned a lesson from the experience.

Shortly after leaving federal custody and just before the 1990s Balkan War broke out, Pavlović returned to his hometown. He says the timing had nothing to do with wanting to get away from Chicago. He holds two passports and he has moved back and forth between both his countries, doing business on both sides of the Atlantic since then.

Dragan Mikerević, a former RS prime minister and a professor at the Banja Luka School of Economics, said he has no interest in Pavlović”s background. What matters, he said, is that Pavlović has invested it in the Republika Srpska.

“I don’t care about how Pavlović has made his money,” Mikerević said. “If there is something suspicious, the likes of SIPA and Interpol can investigate it. That’s their job.”

A businessman of stature in the RS

One of Pavlović’s earliest business ventures in the RS was that bridge over the Drina he first thought of as a boy.

Politicians urged him to think about investing in a factory, but Pavlović’s Bridge, a quarter-mile long span was a symbolic investment.

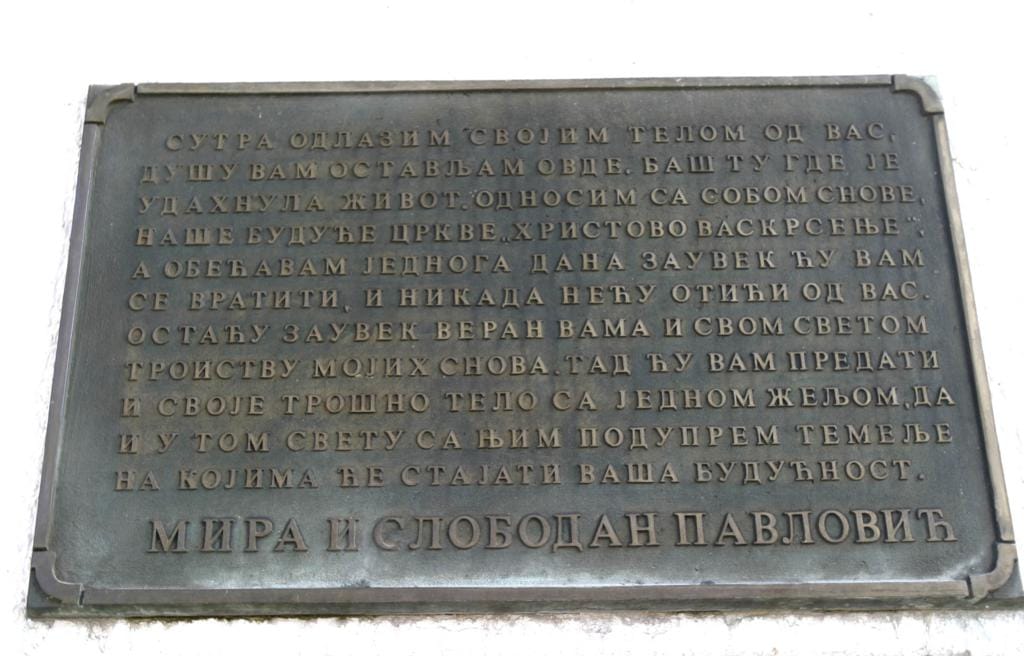

Other symbolic investments were his construction in Popovi of a monument to Serbian protector and hero, Ivo, the Duke of Semberijal. Pavlović also paid for construction of Christ’s Resurrection Orthodox church in Popovi next door to the duplex he shares in the village with the church pastor.

In 1992, at the dawn of war among Serbs, Croats and Muslims in the Balkans, Serbian Prime Minister Dr Radovan Božović spoke at a celebration marking construction of Pavlović’s Bridge.

“I would like to call for unity and harmony for all residents of Serbia, and the entire Serbian nation, for unity on key national interests and goals and differences in political views and political understanding…With his project, Mr. Pavlović proved that the nation on both banks of the River Drina can never be separated or forgotten.”

Pavlović is vocal about his Serb pride but defensive too in this divided country. He says some news accounts in the Muslim-dominated federation entity of BiH have wrongly portrayed him as Serb nationalist.

“I am not a member of the Communist party. I am not a Chetnik,” he said. He doesn’t contribute to any political parties and only donates to what he believes are good programs.

Pavlović has built a synagogue in Doboj and his university accepts students of all ethnicity, even, he points out, a Chinese student.

During the war years, Pavlović paid to bring over two American lawyers to work with RS officials on drafting a declaration of independence and constitution modeled on the U.S. He said he presented to Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić who praised it and apologized to him when his parliament did not approve it.

Pavlović said he does not favor a divided BiH now. As for Karadzic, he still sees him as a man, a doctor by profession, who was pushed into a war he didn”t want. He”d like to see him turn himself into the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague for the sake of progress in the Balkans.

“I was never involved in politics. I was only involved for business,” Pavlović said. If BiH can find jobs for its people – and he said he employs nearly 1,500 — there would be no wars, no problems.

Through his Drina River Bridge Corporation in Belgrade, Pavlović transferred more than $4 million from his Chicago bank accounts to pay for construction that was completed in 1995.He said he sold a building to cover the cost, higher than he expected because he could not borrow money in the RS. He has collected a 1.5 KM toll from every driver over it since. Revenues cover the costs of the bridge, he says.

Privatization of BiH businesses after the war has provided Pavlović with plenty of new opportunities to help his homeland and to expand his business range.

He set up Pavlović International Bank, which then bought up three RS banks, again, not without controversy.

In 2001 Pavlović bought the Semberska Bank in Bijeljina for 1.5 milllion KM in collaboration with partners, including Saul Azar, a partner with him in Chicago real estate. The next year, he acquired and incorporated into his bank the Privredna Bank from Doboj and Privredna Bank from Brčko for 1.2 million KM.

The RS entity prosecutor’s office began an investigation into the circumstances of the Doboj bank purchase, which then Prime Minister Mladen Ivanić approved and still defends, but ended it with no findings. Ivanić told CIN that the sale of the bank was in accord with privatization law.

Pavlović International was the focus of RS Ministry of Interior officials last summer when four masked robbers with automatic rifles held up two bank employees on a highway in Bukova Glava and made off with nearly 2 million KM in various currencies, including U.S. $20 bills. None of it has been recovered nor any suspects arrested, according to the ministry. Pavlović said police officials have instructed him not to discuss the matter.

Pavlović also bought into two food companies: Žitopromet, a Bijeljina processor, and Romanija Sprint in 2004. Records show he paid 1.6 million KM in cash for Žitopromet and the rest in vouchers. In addition, Pavlović is co-owner of a Brčko printing company that recently won a tender to print the annual report of the Central Bank, according to Slobodan Krstić, director of the MOSST Print Company in Popovi.

Pavlović said he”s done buying companies because there are none of any value left in the RS. He wishes officials in his old country would listen to what he”s learned in the U.S. about running companies.

But banking, food companies and printing are small matters in comparison to his dream project – his own city by the river.

Civic vision

Even before the war ended Pavlović began buying up farm land near his family land in Popovo.

The cooperative government of the RS under then Prime Minster Gojko Kličković made the job of land acquisition significantly easier by declaring right of eminent domain over 10 hectares of property upon which he declared he would build an entire new city from scratch.

The government’s action forced even unwilling landowners to sell with Pavlović covering the costs. The process did not go completely smoothly. Eighteen farmers dissatisfied with his offer sued. They say he wanted to give them 2,000 to 3,000 per acre; he said he never paid that little. Six plaintiffs settled out of court, including Željko Trifunović, who got 15,000 KM from Pavlović for 2.2 acres.

“It is true that I have reached a settlement but I feel being cheated,” said Trifunović.

“He’s all the time passing himself as a big-time patron…actually, it’s only money he cares about,” said Trifunović, noting those bridge tolls he pays.

Miodrag Stojanović, the Bijeljina lawyer who represented the farmers, said his clients were not paid until after repeated court motions to freeze Pavlović’s business accounts.

“They kept telling us that they didn’t have money in the bank. They had been putting us off indefinitely,” said Stojanović.

Milomir Rakić said he spent eight years trying to get 150,000 KM for his land. Records show that Pavlović paid off land costs with cash, with shares in his Drina River company and with jobs.

Pavlović told CIN that everyone has been paid and all is taken care of.

Still Slobomir is far from a city. The views out the big windows of the university show a vista of flat, plowed up dirt.

Washington University business professor Vandra Huber was housed in a room at the school when she taught there for a semester last winter. She said she nearly went stir-crazy in the empty city where there are no people and nothing to do. She played with a dog that is the school mascot, she said, and surfed the internet.

The glittering tower that is the planned centerpiece of the place rises only on a website and in a model of the future city kept in the university. Aside from a gateway announcing the entrance to a free trade zone area, the only buildings completed are the University and Pavlović International Bank across a shared parking lot. There are no apartments, stores or restaurants much less the thermal spa and Disneyland Pavlović has talked about in interviews and on his web site.

Still, Pavlović takes government dignitaries, business prospects and journalists, on proud tours around his site. He poses with them at what he calls his “China Wall” a thick concrete dyke holding up a bank of earth. Pavlović says that he raised the sea-level of Slobomir and future tenants will not have to ever worry about flooding here.

Another place to pose is near the life-sized Asian elephant and its baby. Pavlović says he found the statue unused and for sale in Chicago and so brought it to the grounds of his university as a symbol. Elephants are strong and wise, he says on one tour. And, he adds, they are slow too.

The slow growth of Slobomir disappoints him, he said. War and security issues have made investors reluctant to take a chance as he has on the RS, he said, and he doesn”t know how long that will last.

Pavlović touts the advantages above and beyond tax breaks that companies can get in the free trade zone of the city. They can bring in loans acquired abroad for operating inside the zone and companies operating in or managing the zone have the right to deposit foreign currency with the bank inside the zone. But Pavlović International Bank remains the only bank and the only business in the area.

Factories and warehouses have not materialized, despite an offer of land free except for the cost of the infrastructure Pavlović has put in.

The RS government and the BiH Council of Ministers approved the zone, hoping to promote investment in a poor area. The international community opposed it on the grounds that there are too many duty-free zones in the country already. The European Union which BiH hopes to enter one day also discourages such zones as counterproductive to its goals.

Maybe scholarships would have been better

Pavlović has also had trouble finding a long-term international partner for Slobomir University.

He and school officials say they have an agreement with the University of Washington to exchange professors and students. Professors at the American school told CIN, however, that there is no agreement. Told of their comments, Pavlović said it was all a misunderstanding he would clear up.

Slobomir officials have on their website a copy of an agreement signed with Washington University last September.

The American academics say that the agreement was never concluded and they have now backed out of it.

They said the school did sign an agreement to explore the possibility of student and teacher exchanges with Slobomir, but never got a signed copy of the paper back from Slobomir.

The terms of the deal had been difficult to reach agreement on.

As a public university in the US, Washington must guarantee access to all students without regard to religion, race or ethnicity. Slobomir officials, the professors said, removed that clause from the agreement and also wanted a say in just which of their students would be allowed to participate in exchanges.

Troubled by problems at the school that professors Huber and Kelly reported and without a signed document, Washington officials backed out of any arrangement with Slobomir.

The first American university Pavlović approached about setting up an international relationship, National Louis University in Chicago, also refused. Pavlović said an arrangement didn’t work out because of a financial issue.

Professor Ellen McMahon who worked on a feasibility study for Slobomir said officials of her school felt uneasy that Slobomir would be run to make a profit and that it would be all Serbian students.

Kelly and Huber said that the Slobomir faculty was overwhelmingly Serbian and male and that these professors were favored over others. They also criticized professors as old-fashioned and part-timers. Promises to students that they could expect modern teaching and curriculum were not being kept, they said.

Huber said she saw Pavlović as a well-intentioned if eccentric businessman who might have better achieved his aim of helping young people in the RS by funding scholarships for study abroad. But,Pavlović said, he wants to entice young people to stay at home to study.

He said he would work out the problems with Washington. They may be the result, he said, of conflict between Kelly and the president of his university. And he added that he hoped to bring in professors from the University of Illinois to Slobomir next year too.