Amela Adžamija and Kemal Delalić live in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) and regularly pay for health insurance. Yet, neither they nor their underage children enjoy the same rights to health care.

Insurance that Adžamija pays in the Sarajevo Canton should cover all health care costs for her 3-year old child. Delalić from Cazin in Una-Sana Canton has to pay an additional 20 KM a year so that his 4-month old baby gets the same treatment as children in Sarajevo.

Jurisdiction over health care in FBiH is split among the entities and cantons. Each of the 10 cantons adopted regulations on how much citizens had to pay beyond medical insurance, which is why the patients have different costs for medical treatment.

Five years ago, the FBiH authorities adopted a resolution that aimed at evening costs across the board. However, the cantons never subscribed to the resolution on the pretext that there was not enough money for medical care.

The cantons collect more than a billion KM for health care every year.

Financing Health Care

More than 80 percent of FBiH citizens have medical insurance. More than 1.2 million people have medical insurance covered by their employers, labor agencies, pension and welfare funds or themselves.

They are proxies for medical insurance of another 800,000 family members.

The money goes to one entity and 10 cantonal funds that finance 117 health care institutions that employ around 27,000 people. Around 40 percent of the money is spent on their salaries. Somewhat less is spent on drugs and medical supplies, while the rest of the money goes for maintenance and administrative costs at health facilities.

Apart from health care insurance, citizens are required to pay for part of the costs for certain services either through a co-payment or an annual premium.

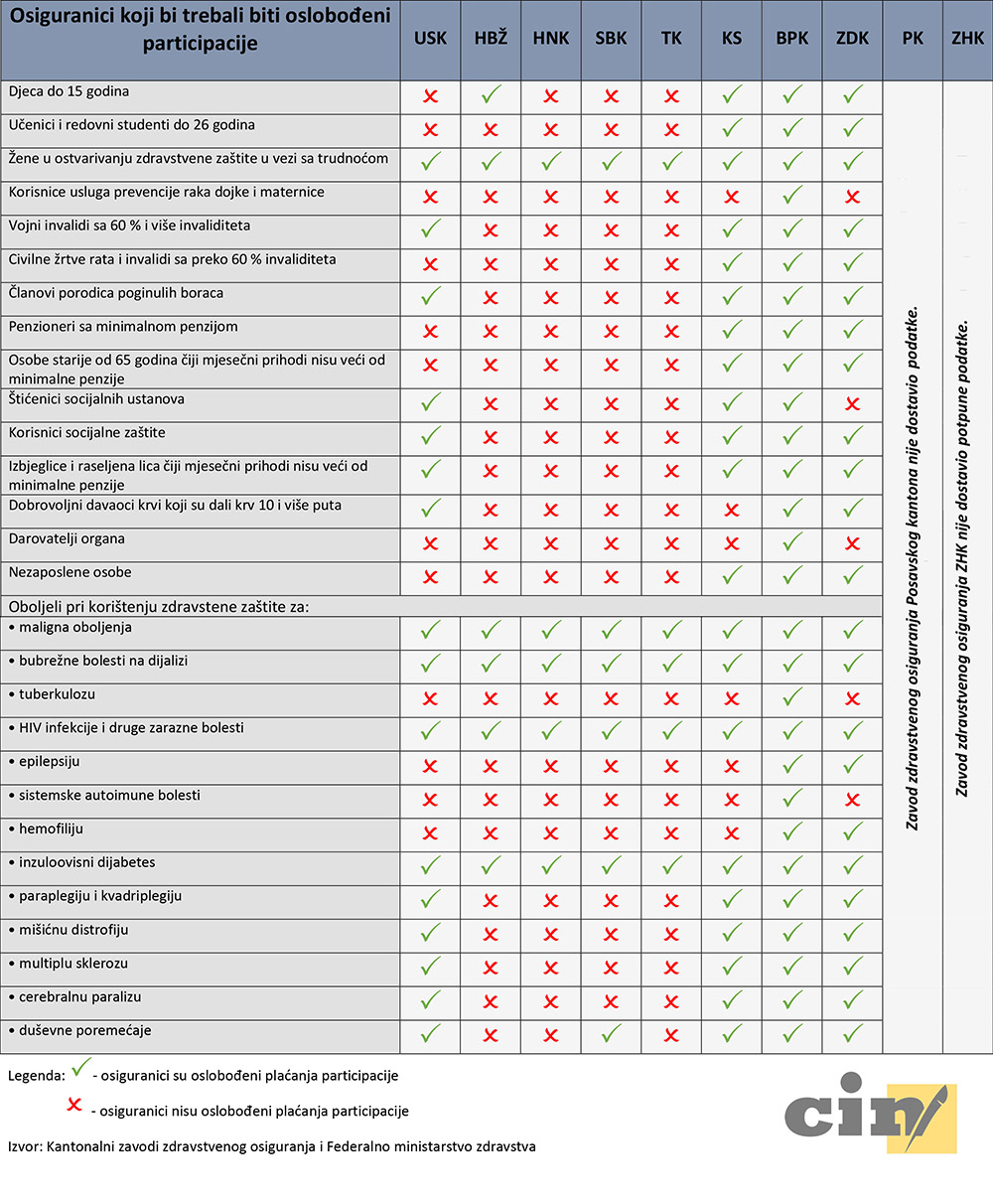

The insured in Bosnia-Podrinje Canton are in the most favorable position as none has to pay any additional costs. The similar situation is in Zenica-Doboj and Sarajevo cantons where the bulk of insured are exempt from extra costs, including pensioners on a minimum pension, the unemployed, civilian victims of war and the disabled.

On the other side of the spectrum, these categories in Una-Sana, Tuzla, West Herzegovina, Herzegovina-Neretva, Central Bosnia and Livno cantons, must pay for additional check-ups. They do this either at every visit or by buying an annual premium that costs between 20 and 30 KM. The Posavina Canton has not shared its records on co-payments with the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN).

Sarajevo Canton has the biggest number of workers who pay for medical care with a salary deduction, and it has the richest health fund with more than 330 million KM going into it a year. Sarajevo resident Adžamija said that she never had to pay for any medical service for her son.

“I think that the parents across BiH proper should have equal rights to health protection of their children,” said Adžamija.

Delalić from Cazin bought a 20 KM premium for his newborn daughter this August.

“I feel deprived because we should be equal at the state level or at least at the Federation level,” Delalić told CIN.

Mirsada Bajramović, a lawyer with a non-governmental organization ICVA (Initiative and Civil Action) has analyzed health legislation in FBiH. She said that the discrepancy among the cantons creates discrimination.

“We have 10 different price lists, 10 different ways of collecting funds and 10 different situations for the insured co-payment-wise,” she said.

In order to erase differences, The FBiH Parliament passed an ordinance on the maximum co-payment that medically insured persons had to pay in 2009. It called for exemption from co—payments for 15 categories of the insured and patients suffering from life-threatening disease Cantons had to make their regulations compatible with this ordinance within 60 days. None has to date. The situation is the worst in six cantons where the premium is paid because the least amount of categories is spared from these costs.

Officials from Una-Sana Canton continued to work in line with their 2005 resolution. Assistant to the Cantonal Minister of Health Aida Blažević said the canton didn’t have enough money to conform to the FBiH Ordinance. The cantonal health fund has at its disposal on average 85 million KM a year. This money is also used to finance two hospitals and eight public health clinics that cater to nearly 300,000 residents.

Still, of all the cantons that charge the premium, the Una-Sana Canton exempted the biggest number of categories from the costs – eight, as well as patients suffering from life-threatening diseases. At the same time, only pregnant women and the gravely sick are exempt from co-payment in Herzegovina-Neretva Canton which has more or less the same amount of money but a smaller population to care for. The cost of premium in Herzegovina-Neretva Canton is 20 KM.

The president of the Canton’s pensioners Alija Tanović says that pensioners don’t have money for premiums.

“I think they went overboard with the price and the pensioners who are welfare cases should be exempt from co-payment. There’s money for sure. Money is spent, disappeared into thin air,” said Tanović.

Herzegovina-Neretva Cantonal Health Fund has around 80 million KM a year at its disposal. According to the Audit Office for the Institutions of FBiH, an average salary at the fund was 1,620 KM in 2011, double the average entity salary in this year. Its employees have received 1,147 KM in vacation allowance plus 1,081 KM as a reward for the Fund’s positive balance at the end of the year, which the auditors considered to be unjustified.

The canton’s officials from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare failed to answer CIN’S question about why they did not harmonize their regulations with the FBiH Ordinance.

Divided Jurisdictions

Officials in the FBiH Ministry of Health are aware of uneven regulations, but say that they cannot do much more than warn cantons to obey the law. The FBiH Inspectorate cannot do anything either.

“The ministry has repeatedly warned cantonal ministries of health about failure to implement the FBiH Ordinance on co-payment, asking them to take measure in this field, but without concrete results,” said Zlatan Peršić, a public-relations advisor at the Ministry.

According to the FBiH Constitution, jurisdiction over health is divided between the entity and the cantons – the entity is tasked with passing laws and the cantons ought to enforce them. However, according to lawyer Bajramović, the regulations have no teeth and those responsible are let off the hook.

Central-Bosnia Minister of Health and Welfare Nikola Grubešić says that they would need more than 20 million KM to implement the Ordinance and that the FBiH sometimes adopts regulations which are impossible.

“You know what that means? The first year we might lock the doors of all public health institutions,” said Grubešić.

Health care in the canton has around 80 million KM a year and with this money it finances five hospitals and 12 public health clinics. Because of the lack of money, some people in the canton have to pay a co-payment for certain specialist services despite having paid the annual premium.

Such is the case of Jajce General Hospital with an annual budget of 2.3 million KM. According to records obtained by CIN, 2.2 million was spent on salaries. Director Dragan Matijević told CIN that the patients are charged for check-ups in seven specialist areas because the Cantonal Health Fund does not cover these costs. According to its job classification, the General Hospital ought to have 74 employees. However, in the past several years, the hospital extended its resources to certain specialist services and today it employs 83 persons. Matijević said that the hospital staff undertook a consultation exercise and decided the specialists were needed.

The Fund and the Ministry officials say that they finance as many employees as the hospital ought to have and that the director should find a way to secure funds for all additional staff.

Patients shoulder the difference by paying three times for the same service: through mandatory health insurance, annual premium and individual co-payments.

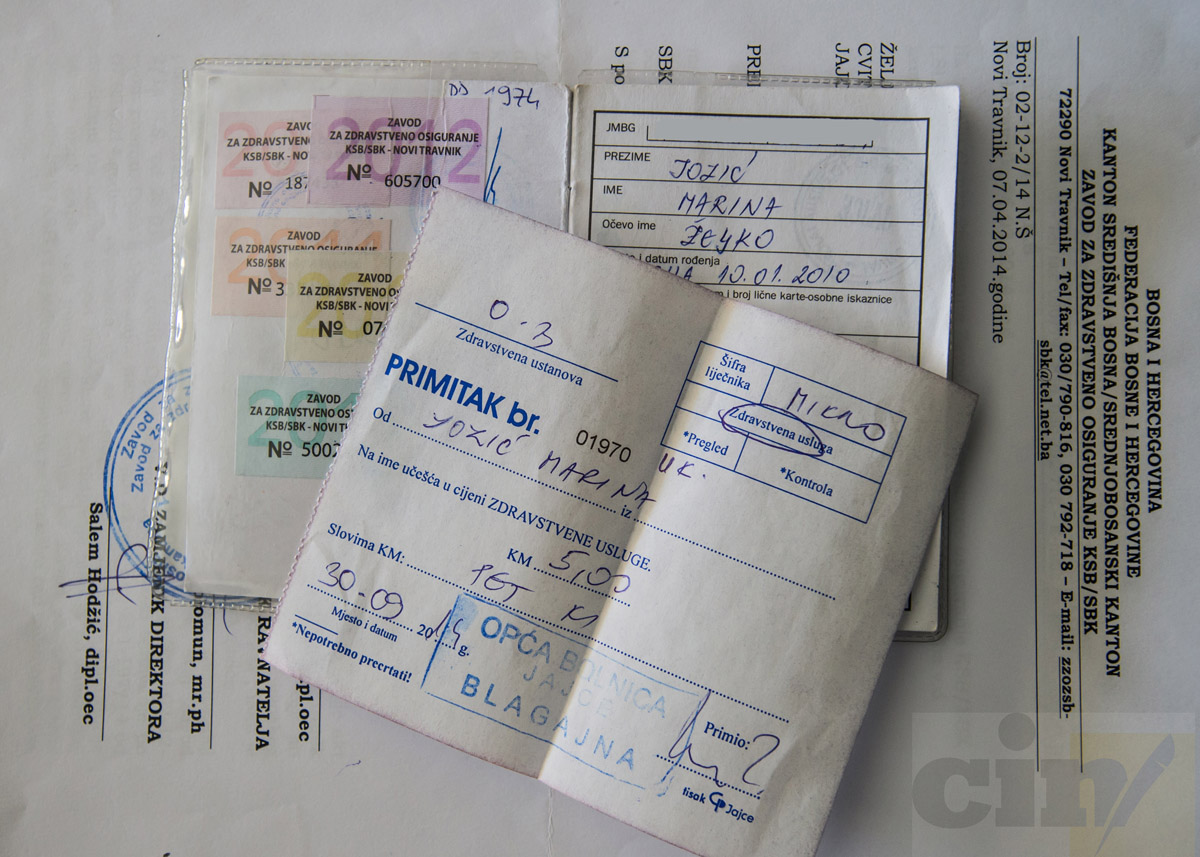

Željko Jozić from Jajce is one of them. In the beginning of the year, he paid 120 KM for an annual insurance premium for his wife, himself and two daughters. When he took his 4-year old daughter to a microbiological lab last year, he was asked to pay five KM before he could collect the lab’s analysis. This happened several more times.

“They are probably trying to make up their salary difference, but I have nothing to do with it. My salary is also late,” said Jozić. He complained to Central Bosnia Health Fund and got some of the co-payment money back.