Even though he did not have to show up for work, a former deputy minister of defense of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Mirko Okolić, received nearly 5,000 KM every month for two years. He was entitled to this as an officeholder.

He’s not alone.

Presidents, prime ministers, ministers, their deputies and advisors, members of parliament and senior managers of some state bodies are entitled to receive a salary for up to a year after their term comes to an end. They can do this because of laws they themselves wrote and adopted at the state, entity and cantonal levels of governance.

They can receive salaries until they find another job or retire. Officeholders receive severance pay even if they are dismissed so long as they have spent one day in office. There is also no limit as to how many times can a person use this discretion.

State and Federation of BiH (FBiH) officeholders are entitled to severance pay for up to a year. All officeholders in Republika Srpska (RS), West Herzegovina Canton (ZHK) and advisors in the FBiH are entitled to six months of pay.

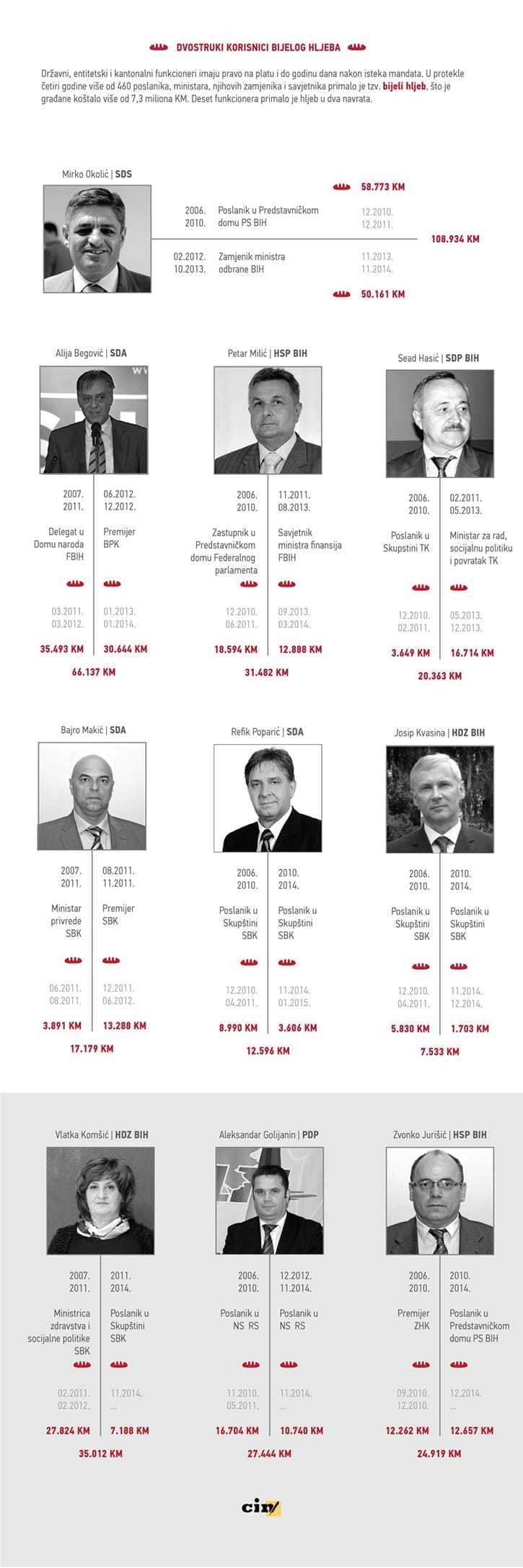

Records obtained by the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) show that 460 officeholders received at least 7.3 million KM in severance pay in four years, while 10 used their discretion twice.

Apart from Okolić, one more officeholder used the privilege for two full years. Taxpayers have spent 175,000 KM just on the two of them.

Two Work Years – Four Annual Pays

A member of Serb Democratic Party (SDS) Okolić failed a re-election bid to Parliament in 2010. Around 10,000 persons voted for him, about third less than at the previous elections.

A month after he learned that he was not going to be a state MP, Okolić started collecting a salary without having to go to work.

According to the Law on Salaries and Allowances in BiH Institutions, Okolić was entitled to receive a monthly remuneration equal to his last salary of 4,833 KM until he found a new job or retired.

“Nothing was done in contravention to the law and this was not a single case. Everyone has done the same,“ Okolić told CIN.

According to the asset declaration Okolić filled in on the eve of the election, he had around 145,000 KM in his bank accounts, an apartment and a car estimated to be worth 210,000 KM total. He also reported a loan of around 11,000 KM.

“Look here, if there’s a legal option and if you expect to receive something which was agreed upon, than it simply happens like that,” said Okolić.

He received severance pay until December 2011, and in the beginning of February 2012 became a deputy minister of defense.

He was dismissed from that office in October 2013, and a month later he asked for a free salary again. Until November 2014, he received 4,180 KM every month.

“Simply, (I) went with the flow. The law say so, so there was nothing controversial about it,” said Okolić.

He did not have to wait for the new job. In mid-December he received a new post – acting director of the newly established Department for Civil Defense in Doboj.

His reimbursed unemployment has cost citizens around 109,000 KM.

The project manager at the Centers for Civil Initiatives (CCI) Adis Arapović said that political parties invented severance to secure jobs for party leaders who lost a term. He considers this one of the worst examples in which politicians decide for themselves how much they need to be reimbursed.

Severance Pay for Doctors in Politics

Just like Okolić, another record holder in time spent receiving severance pay is a former prime minister of Bosnia Podrinje Canton (BPK) Alija Begović.

Begović was previously a cantonal health minister and then the canton’s governor. After this he was an MP at the BPK Assembly and a legislator with the FBiH Parliament House of Peoples.

At the 2010 elections, he won 183 votes – nearly ten times less than at the previous elections – and did not make it into the Cantonal Parliament. He opted for severance pay worth 2,957 KM a month which was his salary at the FBiH Parliament. He also says that he simply used a legally sanctioned privilege.

“I think that the law should have been tailored so that a person can return to his job no matter when he left for politics. If this was the case, I would not have had any problems, nor would I need severance pay,” says Begović.

Begović entered politics 18 years ago after he left the office of Goražde hospital’s director.

According to the Labor Law in FBiH, appointed and elected officials can put their previous job on hold for four years at the most – for the length of a term. Re-election means they lose the right to return automatically to their old job.

Begović got severance pay for three months until March 2012 when he found a new job. The Party of Democratic Action (SDA) appointed him the cantonal prime minister, but he managed the canton for only five and half months when he was dismissed.

Loss of this job did not mean loss of his salary. He asked for severance pay again and continued to receive a salary of 2,553 KM.

Meanwhile, Begović complained to the Constitutional Court of FBiH of an illegal dismissal. “The court deliberated three to four months and I naturally believed that I was going to be returned to prime minister’s post because this was done completely illegally,” Begović told CIN.

The Court declared itself incompetent to deal with his complaint, however, and Begović started looking for a job in his profession. In March 2014, he became a director of Ustikolina public health clinic.

His Kiseljak peer, Vlatka Komšić, former legislator at the Central Bosnia Canton, has spent nearly half of the past four years getting paid for no work.

This politician from the Croatian Democratic Union of BiH (HDZ BiH) is the only one who received severance pay even before 2010. In eight and half years, she used the privilege three times netting 52,000 KM to date.

The blessing of 2,250 KM a month in pay after a term in the state parliament she enjoyed for the first time at the end of 2006.

After that, she spent four years as the SBK’s minister of health and social policy and after she ended the term she used severance pay to the max by receiving 2,320 KM for the whole 2011.

But, this was not the only earning she received from the budget during this period. Meanwhile, she won a legislative term at SBK’s Parliament. She gave up the full salary and professional status in order to continue receiving severance pay and the parliament’s monthly attendance fee. Thus she earned 2,900 KM a month.

“I did not have to take severance pay… I could have gone pro from the get-go, so it would not matter – if I used it or if I were a professional (MP),” Komšić told CIN.

But, it did matter. If she had become a professional MP and gave up severance pay, she would have earned nearly 500 KM less a month, equal to an average pay of a worker in industry, construction, trade and hospitality in SBK.

Last November, she ended her term in Parliament, and as a former legislator, started receiving a severance reimbursement for the third time. Unless, Komšić finds a new job, she may continue to receive 1,797 KM a month until November.

“I’ve acted within the letter of the law which allowed me to get severance pay for a year. I don’t think that this is the worst solution,” she told CIN.

Komšić said that she lives with her mother who has a minimum pension and that her child volunteers so she’s got to have some income.

Arapović from CCI said that all politicians took this reimbursement because the law passed by the governing political parties allows them to do so.

“But, lo and behold, the parties change, but the politics do not. So, whoever got a chance to grab the severance pay took it. Several people refused or took it and gave it to charity, but 95 percent of people took it without a peep, without asking themselves if this was normal, ethical, acceptable and rational in this time of the budget’s crash,” said Arapović.

SBK Officeholders Record Holders in Double Reimbursements

Three more officeholders besides Komšić who used the privilege twice come from this Canton – former cantonal legislators Refik Poparić (SDA) and Josip Kvasina (HDZ BiH) and a former prime minister Bajro Makić (SDA). They used severance pay for shorter time – between four and seven months total – because they were faster in getting new jobs. Their mean monthly salary was between 1,450 KM and 2,250 KM.

Both Kvasina and Poparić followed in the footsteps of their parliament colleague Komšić and received severance pay along with legislators’ allowances and attendance fees so their monthly income between December 2010 and April 2011 was 2,230 KM and 3,012 KM respectively.

Former cantonal minister from Tuzla Sead Hasić (Social Democratic Party BiH) used severance for a total of 11 months – three months as a legislator at Tuzla Canton Parliament in the beginning of 2011, and later for eight months during 2013, as the Tuzla canton minister for labor, social politics and return. During this period he received more than 20,000 KM from the budget.

Petar Milić from the Croatian Party of Rights also benefited twice in the past four years from a salary without no work attached to it. He had a taste of severance for the first time as FBiH legislator during the first part of 2011 when he received 18,594 KM. In September 2013, he used it again after his stint as an advisor to the FBiH finance minister Anto Krajina came to an end. The FBiH taxpayers shouldered another 31,481 KM.

Currently, his party colleague and the party president Zvonko Jurišić receives the severance. As a former state legislator, Jurišić has been taking 3,164 KM a month since last November. Before this, he received the reimbursement as a prime minister of ZHK in 2010 when he received 12,262 KM during three months.

Aleksandar Golijanin, former legislator of Party of Democratic Progress in the Republika Srpska National Assembly, is the only officeholder in the other BiH entity who received severance pay twice and both times as a legislator. First, at the end of his term in 2010, he used the whole six months and received 16,704 KM. He did the same at the end of last year when he started receiving 2,685 KM of reimbursement that will expire in May.

Post-term severance pay has existed for years as one of officeholders’ perks. There was not much talk about it until February 2014, when demonstrators took to the streets. A rally cry to abolish severance pay was one of the main citizens’ requests. Three cantons have abolished severance pay: Sarajevo, Tuzla and Una-Sana and the state has begun the process of abolishing it.

Arapović of CCI said that something like this was not possible before the protests because there was neither political interest nor citizens’ pressure.

“Only after last year’s FBiH protests in February and after these elections closed, we have witnessed that a fast change can take place in a short period of time to the extent that can lead to the full abolition of severance pay,” said Arapović.