In September 2012, a public utility in charge of natural gas in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) turned off the taps to the Birač alumina factory because of several millions KM in unpaid bills. FBiH Prime Minister Nermin Nikšić promptly called then BH Gas director Adnan Kreso.

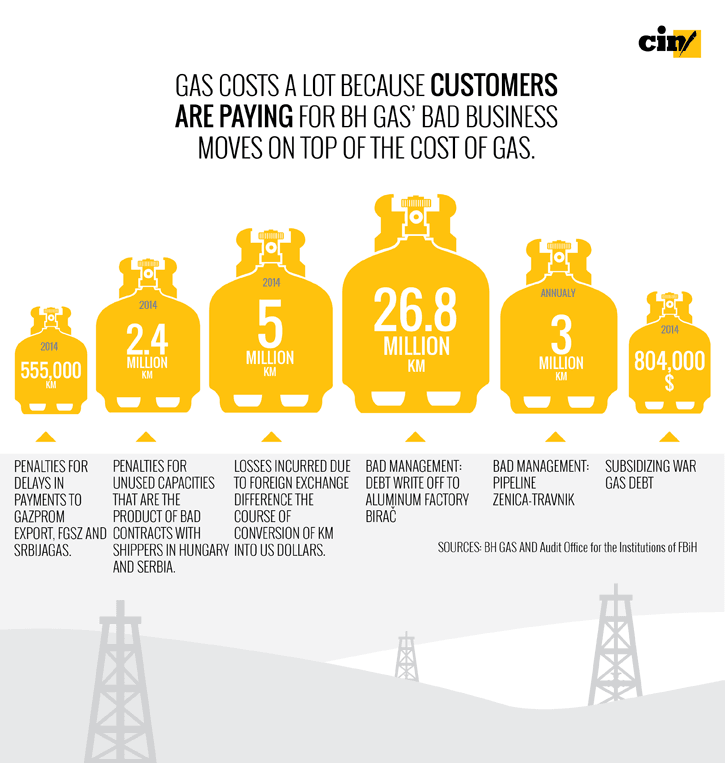

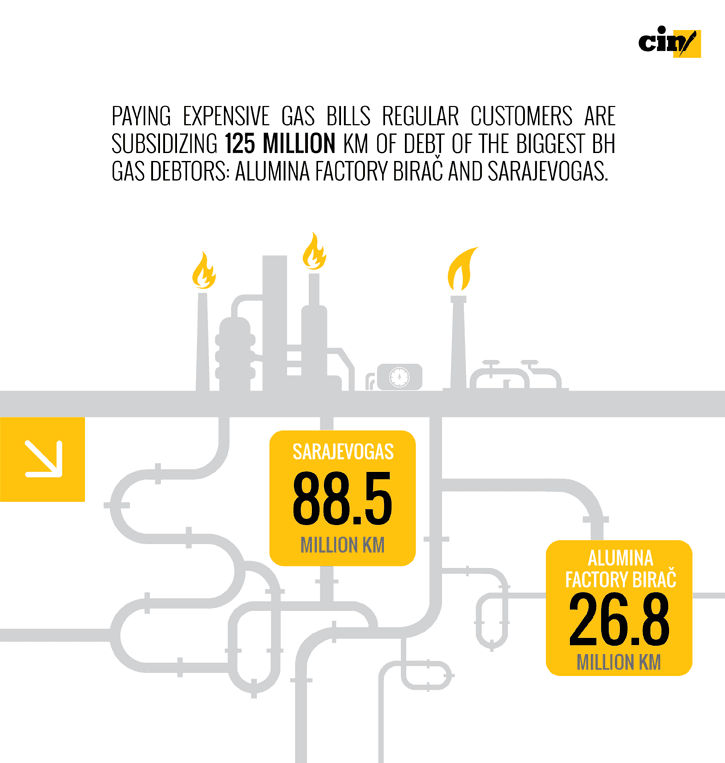

“If the prime minister calls me and tells me ‘Kreso, open them’, I have to. He is the corporation’s owner, not me,” recalls the former director who continued to provide natural gas to Birač because of those verbal orders from above. Soon after, Birač went into bankruptcy leaving 26.8 million KM of gas debt. The question remains if BH Gas will ever be able to collect the debt.

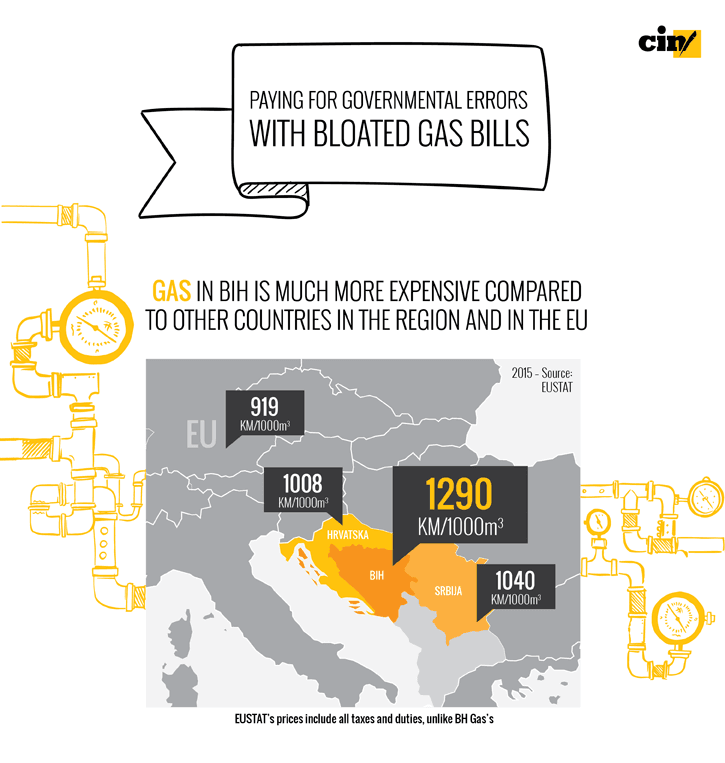

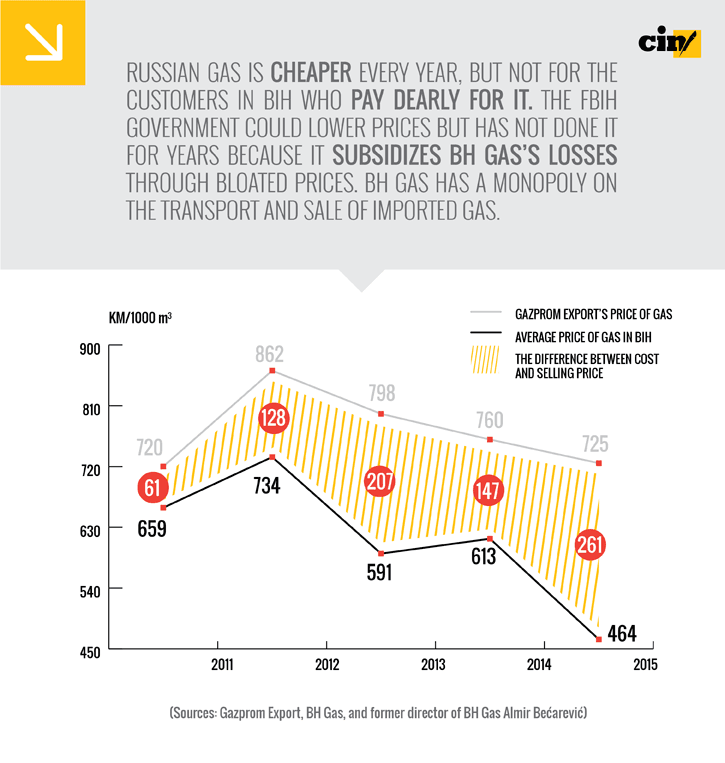

The Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) has interviewed experts who say the company’s clients pay exorbitant prices and, in effect, subsidize the corporation’s losses. Over the past six years, local firms have paid up to 37 percent more than their counterparts in Serbia, Croatia and the EU for natural gas.

Even though the FBiH government could lower the price because it has a say on the price, it chose instead to offset BH Gas losses through higher gas prices. The customers pay for unpaid bills; harmful contracts on the transport of natural gas; bad investments and fees paid to go-betweens as well as for gas bills never paid during the 1992-1995 war.

In December 2015, the price of 1,000 cubic meters of gas was 311 KM at stock exchanges in Vienna and Budapest. That amount of gas is sufficient to heat a 65-square-meter apartment for a year.

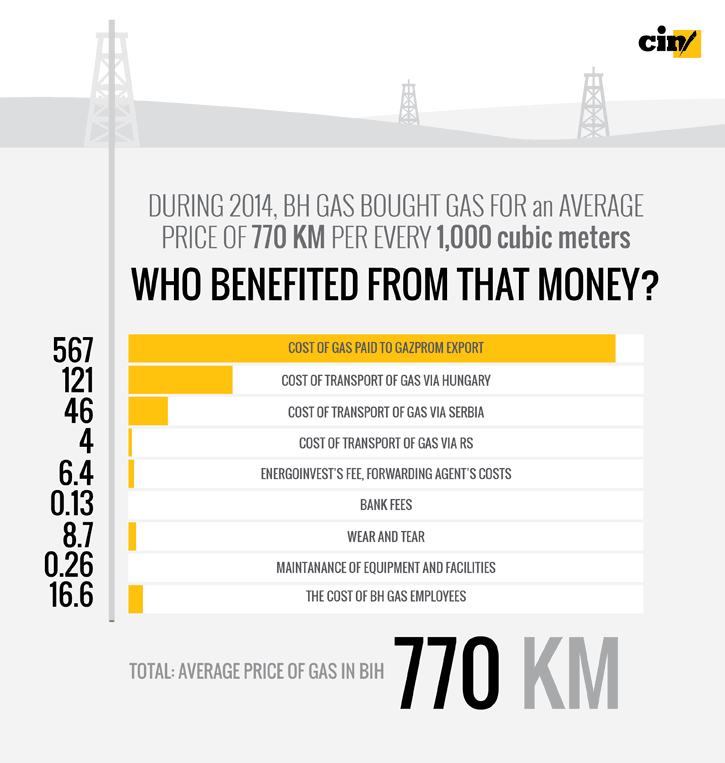

State-owned Energoinvest has a monopoly on the import of natural gas. It does not buy it on the stock exchange but directly from the Russian Gazprom Export which charged 318 KM at the beginning of the year. When BH Gas takes the gas over and adds its expenses to the bill, the price paid by the local firm doubles. Technical director of EPS Laštro from Kiseljak, Ivica Šitum, said that BH Gas recently offered the price of $390 (689 KM) for 1,000 cubic meters of gas.

Businessmen are looking for ways to cut energy spending due to high prices, so EPS Laštro occasionally buys bottled gas and saves 20 percent.

Paying Others Debts

The three biggest users of natural gas in BiH are: Sarajevogas, the Birač plant and Zenica-based Steel Mill- ArcelorMittal. From the founding of BH Gas until the end of 2014, these three companies used more than 93 percent of the imported gas. The biggest user – and its biggest debtor — is Sarajevogas, which supplies citizens with heating gas.

According to BH Gas records, the debt of Sarajevogas amounted to 88.5 million KM last February. Of this 17.2 million is interest. Nihada Glamoč, the director of Sarajevogas, does not agree with interest rates as calculated by BH Gas. She said that the debt of their biggest client – Cantonal Public Utility Company Toplane (Heating Utility) reached 100 million KM.

Director of BH Gas Mirza Sendijarević told CIN how the debt increased prices for customers. BH Gas buys gas in dollars, but sells to Sarajevogas for convertible marks and payments are several months late. As dollar has grown stronger, BH Gas has had to shoulder the exchange rate difference too, adding an additional 5.7 million KM of expenses just in the past 10 months.

“In the end, regardless of the fact that the price of gas has been declining, we cannot reduce the price significantly for customers,” said Sendijarević.

The contract between BH Gas and Sarajevogas was concluded in 2000 for an unlimited time and it provided no guidelines about dealing with default on bills. Audit Office for the Institutions of FBiH recommended negotiating a new contract with Sarajevogas which would define the terms of transfer of authority, and how to measure and calculate gas expenditure.

Sendijarević said that he had tried in vain to make a new contract with Sarajevogas. “We have sent them contracts on several occasions and they returned them without explanation.” The director of Sarajevogas said that she could not accept a 30-day deferred payment asked by BH Gas, and that this was the only point of contention for her.

Apart from the debts of Birač and Sarajevogas, the price of gas in FBiH has also increased the debt of $105 million for gas used but not paid for during the war. For this reason, all customers in FBiH had $5 per 1,000 cubic meters added to their bills since the beginning of 2009. This adds up to around 7.4 million KM.

Bad Planning Leads to Expensive Transport

An Ordinance on the Organization and Regulation of Natural Gas Industry Sector from 2007 is the only document that regulates the natural gas market in FBiH. It gave BH Gas a monopoly on the sale of gas and the control of the 192-kilometer gas pipeline. The remaining 64 kilometers of the pipeline are in the territory of the Republika Srpska (RS) and shared by two entity firms.

In the ordinance the FBiH government gave its other corporation Energoinvest the monopoly on gas import. Energoinvest charges BH Gas a 1 percent fee and it cashed in more than 1 million KM in 2014. This fee also increases the gas price for customers.

Gas is transported via a pipeline from Hungary via Serbia to Zvornik where it connects with a pipeline under the control of the RS companies: Pale-based Gas Promet and Istočno Sarajevo-based Sarajevo-Gas. Since 2014, these companies have taken in 651,000 KM.

The managements of BH Gas and Energoinvest agreed with the Hungarian corporation FGSZ and the Serbian company Srbijagas in 1998 that they would pay for 600 million cubic meters of gas a year until 2019.

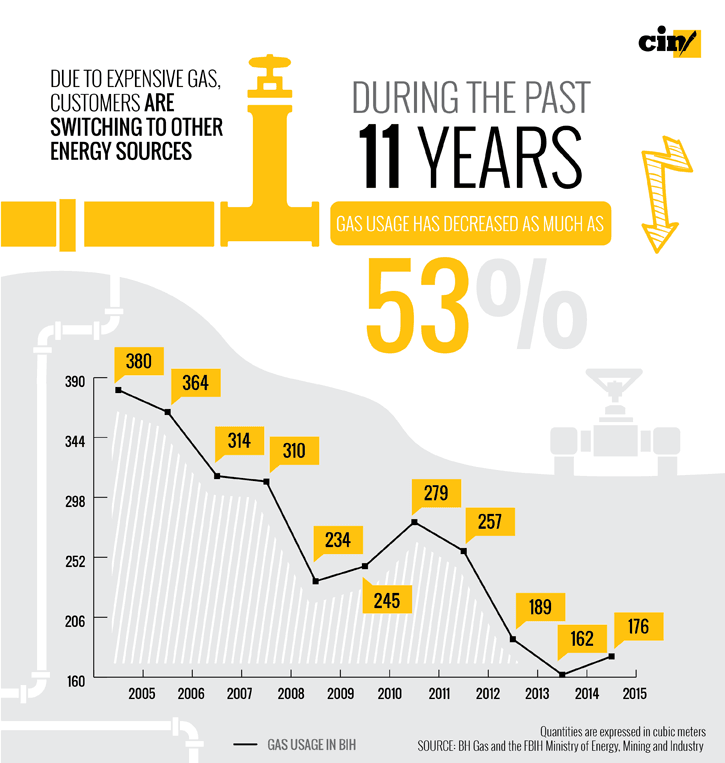

BH Gas Director Sendijarević says that these capacities are underutilized – with average consumption in the past 10 years reaching only 253 million cubic meters. Drawing less gas than promised is punished by penalties.

“When you use less gas, this leads to much higher penalties which significantly increase the price,” says Sendijarević.

BH Gas did not have money to pay penalties for unused capacities and it started signing annexes to the contracts in 2001. These stipulated that BH Gas should pay just a part of the punishment, while the unused capacities for which it paid nothing would be transferred to the last years of contract, “when the situation in BiH would be better with higher consumption,” so it would be able to pay a fine or use the capacities that had been paid for.

However, consumption has instead decreased 53 percent since 2005, so BH Gas paid a 1.53 million KM fine to FGSZ in 2014 and has to factor in the fact that it would be unable to use much of the rented capacities.

According to the original contract, in 2019, the government should have been shipping 1.17 billion cubic meters of gas through the Hungarian pipeline. However, the local pipeline can only take 750 million cubic meters of gas at the most. The fees for undrawn gas between 2014 and 2019 might reach $54 million said Sendijarević. (Around 93 million KM at the current exchange rate).

The costs of breaking the contract with FGSZ would be nearly 20 times smaller, but neither BH Gas nor the government is ready to break the contract fearing a halt in supply as there’s no alternative supply route.

This is why they agreed to extend the contract with the Hungarians which postponed paying off debts to 2023 and decreased the fee for unused capacities to around 28 million KM.

“It’s not ideal, but it helped BH Gas survive and with it, the gas in BiH,” said Sendijarević.

Ten years ago, BH Gas decided to extend its pipeline and reach customers in Central-Bosnia Canton. The first stretch, the pipeline Zenica – Travnik, was only finished in 2013 and it turned out to be an expensive and useless investment.

Over two years, 40 kilometers of pipeline were built at a cost of 41.5 million KM. Even though it was built three years ago, it has still not become operational due to numerous complaints BH Gas had about quality of the work. Poor quality cost the corporation a certificate of final acceptance, and the Federation Bureau for Inspection Affair banned the use of the pipeline at the end of August 2015.

“There is no economic benefit from this. Every year we lose 3 million KM to pay back the loan for something we don’t use,” Sendijarević says.

Political Parties Refuse to Enact Law

In 2007, the FBiH Ministry of Energy, Mining and Industry planned to submit a Gas Act which would demonopolize the gas market in accordance with the European standards to which BiH pledged when it joined the European Union’s Energy Community (EEZ).

All interested shippers were to get an opportunity to transport gas via BiH pipelines and sell it to local firms under equal terms. But this never happened. The former minister Erdal Trhulj says that the ruling parties of SDA and SDP opposed a change in legislation because they have run BH Gas, Energoinvest and Sarajevogas for years now.

In 2007, instead of the act, the government inacted an Ordinance on Organization and Regulation of Gas Industry Sector in FBiH. It is the only document which regulates the energy market that had been unregulated heretofore. The then minister Vahid Hećo did not plan to introduce the act in the following year.

A bill was written only when the minister left office, and it was passed by the FBiH’s House of Representatives in September 2014. In order for the Law to go into effect it has to be passed also by the FBiH House of Peoples, but so far it has not been even put on the agenda. Lidija Bradara, the House chairwoman and a member of HDZa BiH, did not reply to CIN about why the Law has not been put on the agenda.

Unlike the FBiH, the RS passed its Gas Act in 2007 and its 64-kilometers-long pipeline is open to all traders in accordance with the established pricelist. However, the effects are minor because most of the gas is being used in the FBiH.

Trhulj said that the blocking of the law is the result of the lack of knowledge of market and political bickering. He said that unrealistically high price of gas – subsidized by citizens and firms – are the main reason for the opening of the market.

“Gas (prices) would drop right away to $100 to $130 …Why would I pay $350 $400 for gas if I know that the price is much lower in reality?” said Trhulj.

In the beginning of 2015, EEZ chairman Janez Kopač visited the BiH Parliament and blamed politicians for the situation in the gas market. He said that BiH was violating its 2005 pledge to honor the EEZ regulations.

“Everyone wants to help, including us, but there’s no one in BiH who wants to do it,” he said.

Data shows that such state of affairs suits neither BH Gas nor its customers. Despite the monopoly on trade and shipping of gas, the company has fared poorly. Over the 16 years of its existence it had a combined profit of 7.3 million, while three years ago it was on the brink of bankruptcy. Meanwhile, its users are switching to other energy sources.

Šitum of EPS Laštro says that it is hard to pay off piled-up debt and pricy distribution: “Most of the industry would switch over to gas, but no one wants to do it because of high prices.”