A dozen professors lost their jobs in 2002 after students at the Banja Luka School of Agriculture complained anonymously to administrators that they had to pay bribes to pass exams.

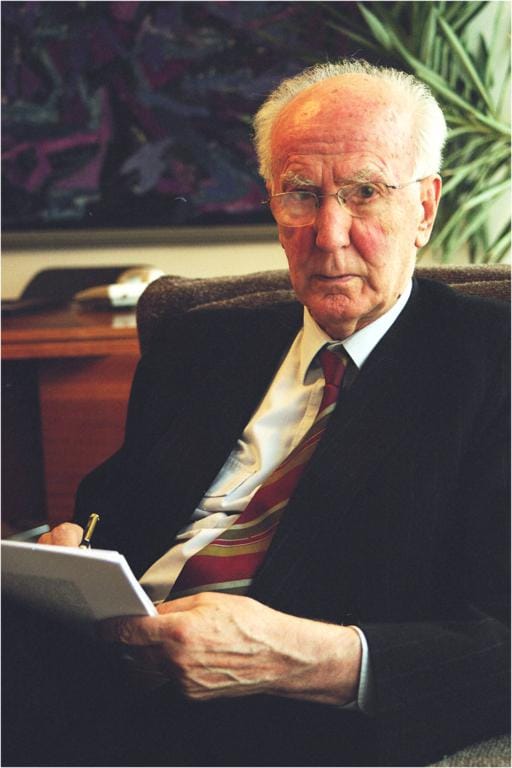

Math professor Miroslav Trninić, one of the 12 whose contract was terminated, doesn’t like to talk about it now that he’s retired and living on a pension.

It’s all water under the bridge, he says, but he adds that he never threatened students with low grades if they didn’t give him money. But they offered and so he sometimes took 50 KM. It was for coffee, they said, and he agreed.

“It was the students pushing it themselves,” he said.

Tuzla Canton prosecutors are considering a corruption case against five professors in the University of Tuzla Electrical Engineering Department. The five were members of a purchasing committee and are accused of accepting an offer three years ago, which included low quality, no-name computers, not the name brand machines a tender required.

Efforts to stop corruption in universities have intensified, including terminations, prosecutions and the formation of school ethics committees. But the overwhelming majority of students and professors remain skeptical.

Students believe that passing exams sometimes requires pay offs of money, favors or allegiance. Professors also say corruption is deep-seeded, but they blame parents and students who pressure them to take money.

To some extent, all involved from students and parents through professors and administrative officials accept corruption as the inevitable result of politics and favoritism. They live with it, without protesting or seeing the way to change anything.

Few are outspoken enough to say, as does Sarajevo Economics professor Meho Bašić: “Universities are breeding grounds for corruption.”

Surveys show certainty about corruption

Certainly many professors and students believe that claims about corruption are exaggerated. They point out, for example, that students who fail important tests will make an excuse to friends that they just didn’t want to pay a bribe.

But most students think otherwise. A June 2004 survey conducted by Transparency International BiH (TI) and law faculty students at Banja Luka University found that more than half of students there see corruption as pervasive in their school. The sample of 299 students talked about giving and taking bribes in exchange for grades and enrollment and about professors coercing them into buying their books.

Another survey by TI, a non-governmental organization dedicated to fighting corruption, showed that more than 60 percent of Sarajevo University students think that coercion and bribing occur regularly.

A survey of Tuzla University students by the non-governmental organization Forum građana showed more than half said they had no doubt that corruption existed and a quarter said it was common.

Many professors who spoke with the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) during a two-month investigation into the country’s universities also saw corruption of higher education as an acute problem.

None was as blunt as Bašić who says he has been offered – but refused — money by parents asking that their children pass exams. He laughed at reporters asking him if corruption existed, “You guys behave like you’re not living in this country,” he said. “I cannot believe that there are professors out there with 10 years of experience, say, who have never been offered money.”

Bašić said such offers are tempting to teachers earning “pitifully low salaries.” There is little corruption in Western European schools, he said, because “a tenured professor in Vienna has 20 times the salary that Meho Bašić has for the same teaching quota.”

And bribes are easy money, he said, because the oral exams students must pass in BiH are completely subjective.

“If I decide to show a student at an oral exam that he doesn’t know his subject matter, I can,” Bašić said. Once you fail a student, you get him to fail another time and before the third exam, the professor said, he’ll be there saying “Here’s 500 KM.”

Sure as he is that corruption is a problem, Bašić and others said they could not prove and did not have solid evidence of any actual instances. The firings in Banja Luka stand out as unusual.

Students accept rather than protest against corruption

Bribery is a secret business conducted away from witnesses. Leveling a complaint can bring unwanted attention and inconvenience and few are willing to speak aloud or to name names.

So, most people accept and adapt to the circumstances they find.

Srđan Blagovčanin, a spokesman for TI, said that Bosnian laws make corruption particularly hard to prove so that most cases wind up as “my word against yours” and convictions are hard to get.

If some leader stood up and took a position against corruption then got community-wide backing, things could change.

“The passivity is an issue,” he said. “Nobody wants to act.”

CIN interviewed seven students at four universities who had witnessed or participated in corruption first-hand in their school as part of this story. None would agree to use of their name, all for the same reason – the fear of possible revenge by their professors.

But they told a similar story about how bribery works. Professors don’t ask outright for money, the students said. They usually have an intermediary, sometimes their teaching assistant, sometimes a senior student or an acquaintance.

Students who pay the professor’s price are supplied with exam questions. One anonymous student said you can usually tell who has paid because they arrive at exams smiling.

Other professors, the students said, earn extra money by coercing students to buy textbooks they have written as a condition for passing an exam. Each student who takes an exam must bring his own copy of the latest edition of the book, a requirement that means students may not share books, borrow them from the library or copy relevant chapters.

Universities try to fight corruption

Some universities have begun to take action against such practices. Four of the eight public universities in the past two years have established ethics committees designed to examine reported cases of ethical violations and to issue reprimands where needed.

Only one of the committees, however, has received even a single charge against a professor.

One reason complaints have been slow in coming is that all but one of them accepts only signed complaints. The University of Sarajevo committee said it has gotten complaints, but because they were unsigned has not acted on them.

Vlado Cikotić, a member of the Ethics Committee of the University of Mostar in West Mostar, the only committee that will act on an anonymous complaint, said it has not gotten any.

“We have not had one anonymous complaint, which is not to say that there is no corruption at our university,” said Cikotić.

The University of Tuzla committee will investigate unsigned ethics complaints against professors if it receives more than one about any individual, but in a year of operation it has not, said Sejfudin Bravac, president of the committee. He does not believe, he said, that student attitudes about corruption as reflected in surveys are reflected in reality.

“If this problem is as prominent as the survey shows it,” he said, “wouldn’t there be one student to send a complaint against his professor?”

In stark contrast, Edin Delić, president of the union of higher education, said his organization has received so many tips about corruption at the 17,000-student university he has begun talking about “The Anonymous Tipping Madness.”

Delić said anonymous complaints were a problem to deal with. Someone gets angry with a professor or just doesn’t like him and files a complaint. Names get smeared this way, he said.

Delić said police and prosecutors are better able to deal with corruption in schools than committees. “Society,” he said, “cannot expect that we can follow every step of all our colleagues,” he said.

Zenica University, the University of East Sarajevo and the University of Džemal Bijedić in Mostar have no ethics committees but have administrative policies for dealing with ethics complaints. None reported any cases. The University of Banja Luka is the fourth school with no committee.

One other reason that ethics committees have so little to do, however, may be that students are unaware they exist or don’t trust them.

Four months ago the Ethics Committee of Tuzla University sent a notice to the university’s student association talking about its activities, said Bravac. The association was supposed to inform students and encourage them to report any soliciting of bribes.

But Association President Izen Hajdarević said no such notice ever came. He also said that he was not aware that a committee was looking into corruption complaints. His association often receives such complaints from students.

Asked what he has done about them, Hajdarević said, “Nothing. They are anonymous.”

Rizah Čizmić, a member of the umbrella organization of Sarajevo students (USUS), said most students were unaware of their rights in battling against corruption.

“This might be written in the statute of the university, but who’s reading the statute?” she said.

Both student representatives suggested that a campaign is badly needed to inform students about ethics committees and about the need to report corruption. They say they don’t have enough money however to print notices and advertise the work of the ethics committees.

Even students who know about their right to complain against corruption don’t. “Students are afraid of consequences,” said Cikotić.

Professor Adelija Čaušević of the Pharmaceutical Faculty in Sarajevo agrees: “Students are afraid to report on a professor because of the fear of professors’ revenge.”

Adi Kolasević, a member of the FBiH Association of Students who attends the Sports Science School in Sarajevo, said students can see the safest thing to do about corruption is nothing. When they have made individual efforts to stop the problem, it has not worked out.

He pointed out that no students serve on university ethics committees, even though students are often the victims and professors on the committee are unlikely to criticize their colleagues.

“Why would I accuse my fellow professor of soliciting bribes if I can help him?” said Kolasević. “Professors are keeping each other’s back.” Instead, an outside oversight body is needed, he said.

Bašić suggests that foreign professors should serve on ethics committees and that international prosecutors should take some cases of bribery into court. The way to stop corruption is to bring some high-publicity cases against big names, he said.

Students don’t want to get involved in the clean up

In Sarajevo, USUS tried to address the problem by having students evaluate the competence and ethics of their professors. When Denis Čamdžić, president of the USUS informed the University Senate of their plans for regular evaluations, which is a recommendation stemming from the Bologna guidelines, officials from some departments protested.

“I’ve asked for their approval only to see how they will react and to see who of them will be against it,” said Denis.

Students have just one representative in the Senate, Denis noted.

But students must take more responsibility for corruption in their schools, according to many BiH academics.

Too many are like Minela Ramić from Zenica, a senior in the Tuzla School of Abnormal Psychology and Learning Disabilities, who told CIN that she couldn’t talk about bribing-for-grades cases at her school.

“When I enrolled in the university my sister told me: ‘Pretend. What you see, you see not. What you hear, you hear not.”

Muhamed Filipović, a long time professor and university official, put it this way: “Students are corrupted as well, because they don’t want to put in any effort. I know of many students who don’t want to study, just to go with the flow, but they want a degree.” Paying a bribe to pass an exam or get into a course is an easy way to get that degree.

In a recent survey, some 10 percent of Sarajevo University’s 54,000 students said they would be willing to pay to pass an examination.

One of them was 25-year old Dragan Bender, a soon-to-graduate student in the political science department. He said his only worry would be the expense involved.

“If he kept flunking me at the examination and if I knew that he was taking money, I would pay too, only not more than 200 KM,” said Bender.

That attitude disgusts Dragan Mikerević, professor at the Banja Luka School of Economics. “I express disapproval of students who think that they can pass an examination in this manner,” he said. Such corruption will have catastrophic consequences for society and for young people.”

Professor Azra Hadžiahmetović of the Sarajevo School of Economics agrees.

“Bribery for students is like a shot in their foot. They are the future intelligentsia in this society where a piece of paper (diploma) will signify little,” she said.

Asked about what students might do to stop corruption, Kolasević of the FBiH students association suggested that they unite and demand action.

“If all students from one department came out and said that this professor is taking money” it would “create pressure on professors and media.”

He is pessimistic about this happening, however. “That is hard,” he said, “it is more important to drink coffees every day.”

Mikerević suggested fighting corruption by pushing clear ethical guidelines for professors. But decent pay and societal respect for academic jobs also is needed, he said. Professors proud of their work would be ashamed to take bribes.

Powerful forces favor corruption

Even the increasing number of young Bosnians enrolling in universities, which seems like a good thing, adds to the possibility for corruption, because it creates demand for admission into schools.

“The limited number of entries and an enormous number of interested are a breeding ground for corruption” said professor Čaušević.

In a society where families typically look out for relatives, nepotism is another source of ethical problems in universities. Professor Šemso Tucaković of the Sarajevo School of Political Sciences, noted that, ”The children of professors, cousins, become professors and PhD’s themselves because their parents can pull strings and connections and this breeds an elite-to-kill-for which is pushed through the connections by their parents and cousins.”

“It happened to me that they would come with a bottle of whiskey and some gift and say: for old times sake, please look after my this and that.”

A tradition of gifts and showing appreciation makes bribing seem more acceptable.

“People are used to soliciting all kinds of favors – money, sexual and work,” said professor Filipović. “The way I see it is as if there’s a big gap between students and professors. It all comes down to some sort of trade.”

Professor Lamija Tanović of the Sarajevo School of Mathematics and Natural Sciences sees a ray of hope in the introduction in BiH of the Bologna guidelines for reforming higher education.

Bologna stipulates that all exams be taken in writing, for example. Exam papers marked with student identification numbers instead of their names means professors don’t even know whose paper they are grading.

Tanović said that the Bologna way of evaluating students throughout a semester of performance rather than in one exam prevents corruption. Students build a track record of work throughout the school year, and their final grades are arrived at by calculating achievements in addition to the mark on one big final test.

But Hadžiahmetović, who has called for better ethical behavior in universities, is not optimistic that ridding BiH schools of corruption will be quick or easy.

“Corruption is a pathology that generally marks BiH society,” she said. “In part it is the product of our poverty – material and spiritual. It stems from thinking integral to our mentality… Even before we eventually try to do something, in advance of that, we think about how to open doors to solve the problem earlier.”