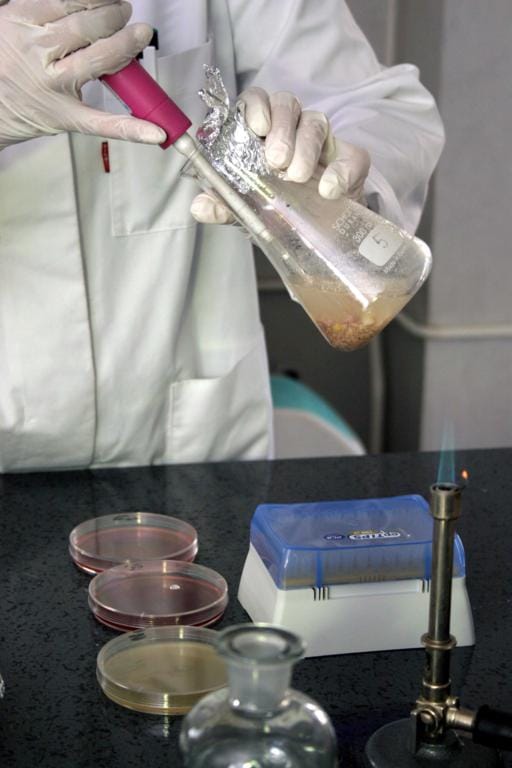

Nearly half the dishes the School of Veterinary Science in Sarajevo analyzed in a food safety experiment by the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) contained elevated numbers of microorganisms or were contaminated by bacteria associated with food poisoning and food spoilage.

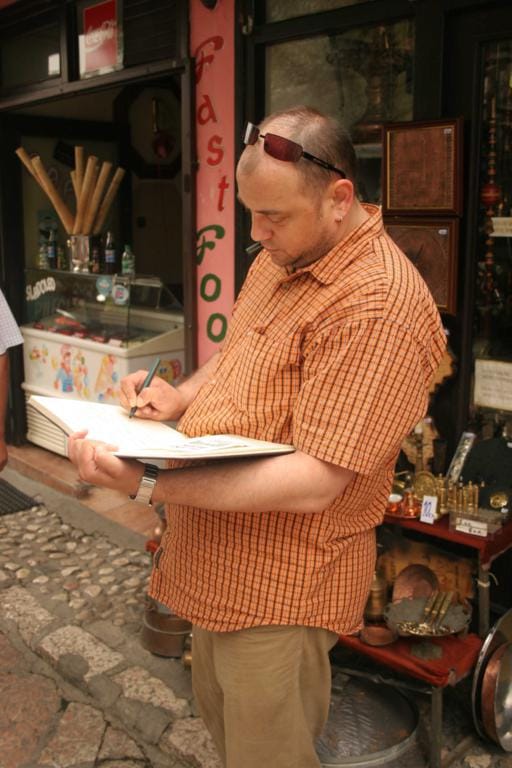

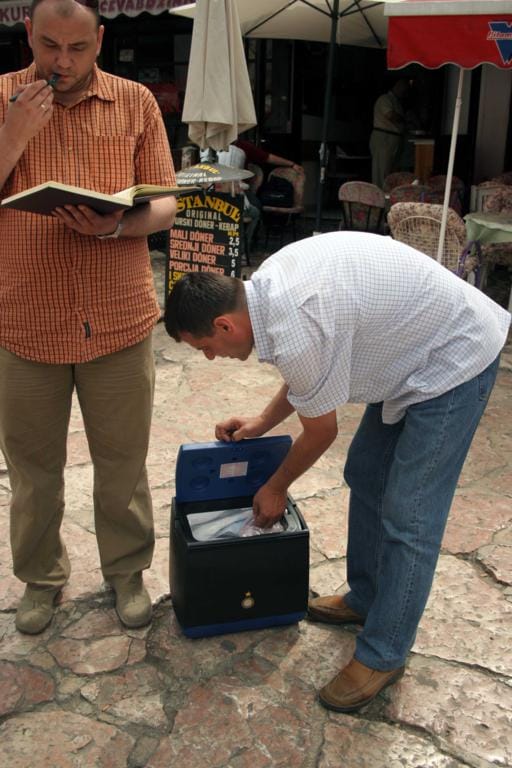

In the test, 95 food items were purchased between May and July from randomly selected restaurants, fast food, ćevapi, ice cream and cake shops in Sarajevo, Banja Luka and Mostar.

More than 49 percent of these samples showed numbers of microbes considered unsafe or they contained E. coli, staphylococcus, proteus, lipolytic bacteria, yeast and mold.

Proteus, lipolytic bacteria and yeast and mold all indicate that food is old or has been prepared in unhygienic surroundings or by dirty hands. The others can cause food poisoning with symptoms of vomiting, fever, nausea, dehydration, and in extreme cases, especially in cases of allergy, death.

More than 70 percent of the contaminated samples contained more than just one of these bacteria or they showed both a high number of microbes and the presence of a dangerous type of bacteria.

Unacceptable numbers of microbes were found in much-frequented shops that sell pies and ćevapi and in expensive, high-profile restaurants. Contaminated food was found both at indoor markets where a veterinary inspector regularly checks food and in the stalls of street vendors where food is not tested at all.

Asked about the results of the CIN experiment, Mato Brstilo, director of the Veterinary Office at the Croatian Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management and Forestry, said that all findings of E. coli and proteus were proof that the food was bad and could be dangerous for health. David Daigle, a spokesman for the U.S. National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne and Enteric Diseases, agreed that ‘any presence of E. coli in food should be considered a public health concern.’

Hasan Džinić, the head of veterinary inspection for the Canton of Sarajevo, said he was surprised looking at the test results that food poisoning wasn’t a bigger problem. Kajmak, he said, showed up as a ‘biological bomb.’ Džinić said his staff would study the CIN experiment and follow up on it.

Tests of small samples like CIN’s provide a snapshot of the food safety situation the people of BiH face today. They do not indicate the full extent of the danger. But the results suggest that no restaurant, fast food, ćevapi or cake shop should be regarded as absolutely safe. Consumers must beware.

And food handlers must be more careful.

Veterinary school experts say high numbers of microorganisms and the presence of proteus and lipolytic bacteria are certain signs that kitchen staffs have not cleaned their hands or thoroughly cleaned the utensils, equipment and premises where they prepare and sell food.

CIN had 10 Sarajevo food places tested a second time after analysis of items purchased in them showed positive bacterial results. Food from six of these tested positive again.

Restaurateur Nihad Mameledžija said he was shocked when told that staphylococcus which can cause headaches, cramps and changes in blood pressures were discovered twice in food bought in Slick. He promised to review hygiene and purchasing procedures to ensure that no customer needs to worry. The restaurant buys fresh produce and meat, he said, and his six kitchen workers have been trained in keeping things sanitary.

Amer Sinanović, the owner of Hacienda, also vowed to reemphasize cleanliness and care after learning that food from his restaurant tested positive twice for proteus. The first test also showed staphylococcus and E. coli, which can make people sick.

Sinanović wondered if food he buys from the market could be to blame but he agreed that it was ‘in everyone’s best interest to do well’ at serving clean, healthy food, including his own family and his 30 employees and their families who depend on Hacienda paychecks.

The Kurto cevapi shop in Sarajevo’s Baščaršija is renowned for its Turkish specialty, doner kebab. Analysis of this food found three types of bacteria – proteus, E.coli, and staphylococcus. A second analysis 20 days later found E. coli again.

The shop is about to celebrate its 30th anniversary. A son of owner Mustafa Kurto protested that ‘If somebody was to get poisoned, it would have happened sometime in the past 30 years.’

Other places that tested positive twice include two stalls at the City Market where CIN purchased sour cream and soft young cheese, and Marinero restaurant.

Counting the number of people poisoned

From 2000 through March of 2006, more than 7,000 BiH citizens at least felt the debilitating effects of food poisoning. Radovan Bratić, an epidemiologist from the Institute for Citizens’ Health Protection in the Republika Srpska, said the number of cases dipped in 2004 and early in 2005 but has been on the rise in recent months.

In the first four months of 2006, more than 230 people sought medical assistance for vomiting, fever and dizziness typical of food poisoning.

Dr. Fikret Pinjo, chief of the Department for Infectious Diseases at the Clinical Center of Sarajevo University, said his department hospitalized 726 patients from May 2005 through May 2006 and 348 had digestive tract problems. Dr. Enisa Bećarević said more than 100 patients come into the Sarajevo Emergency clinic daily and five or six can be relied on to have stomach problems.

But getting at the real number of people who get sick from eating is difficult because in most cases they never go to doctors and so are not counted. They stay home, sipping tea and taking non-prescription medications available from drugstores.

Alma Babović, a pharmacist for 25 years, says there is a huge demand for medicine in the drugstore in Baščaršija where she works. ‘In summer we have about 40 percent more customers seeking help because of stomach problems’ she said. ‘Nobody wants to go get a check-up to see why the poisoning happened. Everyone just wants the medicine.’

Davor Alagić, senior assistant with the Department of Food Hygiene and Technology at the Veterinary school, said food poisoning is underreported in BiH both because people don’t rush to doctors here for every little thing and because doctors simply treat these cases without seeing a need to track down the cause and source of contamination.

Numbers and details about what CIN found

Veterinary School experts together with CIN reporters bought a total of 95 food samples.

These included commonly eaten food cevapi and pie. International dishes such as pizza and Mexican food, fresh cheese and ice cream were also sampled.

Laboratory analysis showed problems with food in all three cities. Fifty-five percent of 20 food samples gathered in Mostar were positive for bacteria, as were 50 percent of 20 Banja Luka samples and just over 47 percent of the 55 Sarajevo foods.

In no food samples were there any signs of salmonella or clostridium, bacteria that can cause extreme illnesses.

Proteus showed up most often in the contaminated samples, in 27. Proteus does not make people sick, but its presence in food, according to experts, is a signal of fecal contamination.

E. coli, fecal contamination that can make people ill, was found in 26 samples. Staphylococcus appeared in 23 samples.

Twenty-three of the samples showed an unacceptably high number of microorganisms, another sign of stale or expired food. Old state regulations never required this test for dairy products. Nearly 68 percent of the foods in the experiment that the test was required for had unacceptably high counts.

Two of five foods with high milk-fat content tested, for the presence of lipolytic bacteria had it. Both of the food samples tested, as they should be by regulation, for yeast or mold — signs of spoilage — were positive.

Dairy products did not do well in the test. Ten of 13 samples were found to be unsafe. Both products bought at the renowned 112-year-old City Indoor Market in Sarajevo and from street vendors had bacteria, though many people think buying at the market insures they will get safe food.

Popular hot-weather deserts did not do well. Two cakes in Mostar were sampled; both were found unsafe. Bacteria were found in six of 14 samples of ice cream taken Of meats and other main course entrees tested, 29 out of 66 samples were found to be bacterially suspect.

In a separate testing of snack foods, CIN had 15 additional samples of pistachios, banana chips, dried plums, raisins, shelled and unshelled peanuts, almonds, walnuts and hazelnuts analyzed at the Veterinary school. Three of these tested positive for alfotoxins, chemical substances from fungi that may be carcinogenic.

What can be done

Kurto thought its food was safe. The owner’s son showed CIN reporters a document he said came from Sarajevo cantonal veterinary inspectors proving his meat was safe.

‘The bacteria which you have found could be in the salad or tomatoes’ he said. ‘There’s no way it can be in meat which is fried at 100 degrees Celsius.’ He said that when testing doner kebab, inspectors sample only the meat, not the bread or salads customers are also served.

Džinić confirmed that his inspectors only test animal products, and not bread and salads. The Veterinary School analysis involved mixing all the individual products of a sample together, bread along with meat and vegetables, just the way people eat them.

Asked who was responsible for testing non-meat products, Džinić said: ‘Sanitary inspectors if they wish to do so.’

Džinić also strongly denied Kurto’s claim that his inspectors issue documents which guarantee the safety of restaurant food.

‘These documents the owners get after paying one of the private labs to test samples of their food once a month’ said Džinić. He said this practice is meaningless because food has to be scrutinized daily.

‘All that food which goes on sale without testing is a big risk to those consuming it’ said Džinić.

But the Veterinary School found that items such as sour cream and clotted cream on sale in the Sarajevo City Indoor Market where sanitary inspectors are on daily duty also contained bacteria.

Džafo Suljo, general manager of the government-owned chain of markets that includes the City Indoor Market, said he has received no customer complaints. He said that the market employs a veterinary inspector who takes random samples of food daily for testing.

Džafo acknowledges that vendors ‘ought to have protective aprons, gloves, and hats while on duty.’ He said veterinary inspectors should do training to teach vendors about food handling and customer service.

Some vendors wear aprons, but few wear gloves or hats.

Experts agree that inspectors working with restaurant owners and vendors and doing regular and complete checks of food being served could help spread awareness and reduce the bacterial danger lurking in food.

Consumers can take precautions too. Alagić said many Bosnians get some protection against food poisoning by their cultural inclination toward well-cooked, well-done foods.

‘Thorough rinsing, cleaning and disinfection of everything that comes in contact with the food are important’ he added. ‘These measures are especially necessary in summer’ he said, ‘when high temperatures turn food into a breeding ground for microbes.’