Since the Republika Srpska (RS) government requested to terminate the contract on the privatization of the Banja Luka Tobacco Factory and announced it will seek a new buyer, the worker’s union has feared that the business’ attractive downtown location would be the real draw and not cigarette production.

The factory has been piling up millions in debt, its machines are obsolete and the owner has sold more non-house brands than his own cigarettes. Documents the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) has collected show that the factory was erased last year from the Banja Luka Regulatory Plan. The plan instead features business and accommodation units in this central downtown area.

Nebojša Antonić, who privatized the factory, was arrested this August on suspicion of committing customs fraud. The RS government filed a motion in mid-September with the District Court in Banja Luka to terminate the privatization contract with him.

RS Prime Minister Aleksandar Džombić said that the government would seek a new strategic partner for the factory, provided the contract is terminated.

However, the president of the factory’s union Miroslav Marinković said that the zoning plan would be a magnet for would-be buyers out for a prime location rather than the production.

Hotel Instead of Factory Halls

In May 2007, eight months after the privatization, city authorities began to amend the Banja Luka zoning plan and the regulatory plan of the Center Alley where the factory is located. The zoning plan called for relocation of the factory, while the regulatory plan defined the purpose and the size of the new buildings in the area.

Photo by CIN

The RS Institute of Urbanism was hired to develop both plans but went in receivership before zoning plan was finished. The town council adopted the regulatory plan last December.

Zoning experts say that the plan gives the owner the chance to turn the factory into a hotel and to tear down warehouses and administrative buildings to make way for malls, banks and restaurants.

The city and Institute officials ducked questions from CIN about who initiated zoning away the factory. Institute planners said, instructions for the change came in the draft of the Banja Luka Zoning Plan.

Mirjana Sinadinović, head of the Institute team that worked on the regulatory plan, said that technical solutions were based on decisions made by officials from the Department of City Planning.

Former Institute employee Snježana Mrđa-Badžo said instructions from city officials contained requests from private investors who wanted the plan amended. She said that an investor is considered any person who owns real property within the confines of the plot.

Sinadinović said that during development of plan they met with Antonić at the factory’s offices. She said he was especially interested in new solutions and asked questions about the possible changes of the plan.

The proposal for the regulatory plan was done in January 2010. A month later it was put up for the public discussion and the land owners had the opportunity to comment and argue the proposed solutions. The tobacco factory sought permission to increase the number of floors as well as to tear down the factory.

It got permission for extra floors but the demolition request was rejected because the halls represented a cultural and historic building from Austro-Hungarian times and was under government protection. However, the plan still allowed for the historical building of the factory to be turned into accommodation facilities.

Photo by CIN

Union leaders and the heads of the Association of Minority Shareholders said that they did not know about the procedure for changing the regulatory plan, or that it was up for public discussion or that the plan got passed. City authorities published notices in the official gazette and at the website of the city government, but none of them made it clear that the intention was to change the purpose of the land on which the factory was located.

Factory’s director Simo Miskić told CIN the company was not planning to move the factory to another location, which is why they did not notify the workers about the changes in the regulatory plan.

Union president Marinković said that they learned about the new plan from the private sources in the beginning of summer. After the arrest of Antonić, the workers wrote to the RS government asking it to stop destruction of the company that had begun five years earlier and to do something to stave off bankruptcy and liquidation.

Prime Minister Aleksandar Džombić said that the workers informed the government that the majority owner had been waiting for the contract to expire after which he the factory would go toward bankruptcy so that he could use the land for what the regulatory plan established.

Privatization of the Factory

In September 2006, Antonić bought 55 percent of the factory’s capital for 2 million KM via his Laktaši firm Antonić Trade. In the privatization contract, he pledged to invest 4.7 million KM over three years into the factory, and to increase the number of employees to 350. He also said that he would keep the factory’s principal activity – manufacture of cigarettes – for the following five years.

Antonić failed to fulfill his obligations, say the workers. However, the government-owned Investment and Development Bank (IRB), which monitors privatization, reported for years that the investors stuck to the contract.

Two months before expiration of the contract, the prime minister in his expose on the reasons for requesting contract to be terminated said that the firm’s financial stability was endangered, and that its principal activity had been changed. He also said that contractual obligations of investments have not been fulfilled.

Photo by CIN

In 2007, Antonić bought second-hand equipment for the production of cigarettes with which he tried to fulfill his privatization obligations. He got them from the Tobacco factory in Zagreb which in turn was owned by the Rovinj Tobacco Factory. Antonić is the Rovinj firm’s BiH representative.

However, he did not install the machines by 2009, when the RS government prolonged the fulfillment of the investment to another two years.

Zoran Popović, IRB’s public relations officer, said that the majority owner should have either installed the machines or sold them by the due date of his contract. The money was to be paid to the factory’s account.

Popović said that Antonić wired to the factory’s account around 1 million KM in cash, while he invested around 3.5 million KM in equipment.

Antonić said he could not physically haul the machines into the factory. He asked for permission to demolish the halls, but he was not allowed because the factory was part of historic heritage. Workers say that he knew well what the factory’s halls were like before he bought the machines. Marinković said that the RS government and IRB continued to tolerate Antonic’s failure to honor the contract.

In its report, the union said that the factory has turned out less than half the planned production of cigarettes, while increasing the sale of foreign brands through the factory’s retail network, which means that the owner violated the agreement in which he took an obligation to keep the principal activity.

The Factory Ended the Year Negatively, Antonić Positively

The workers say that Antonić used the factory to enrich his private company Antonić Trade even though he obliged in the contract that he would not bring adverse business decisions.

Instead of buying goods for the factory directly from the suppliers, he did it via Antonić Trade which increased the factory’s operational costs. The factory did not pay for the goods and services which is why it owed nearly 7.2 million KM to Antonić’s private firm by the end of 2010.

Photo by CIN

Antonić Trade’s financial documentation shows that the firm has done well for itself between 2007 and 2010. While the tobacco factory piled up losses of 3.1 million KM, the net revenue of Antonić Trade was around 12.8 million KM at the end of this period.

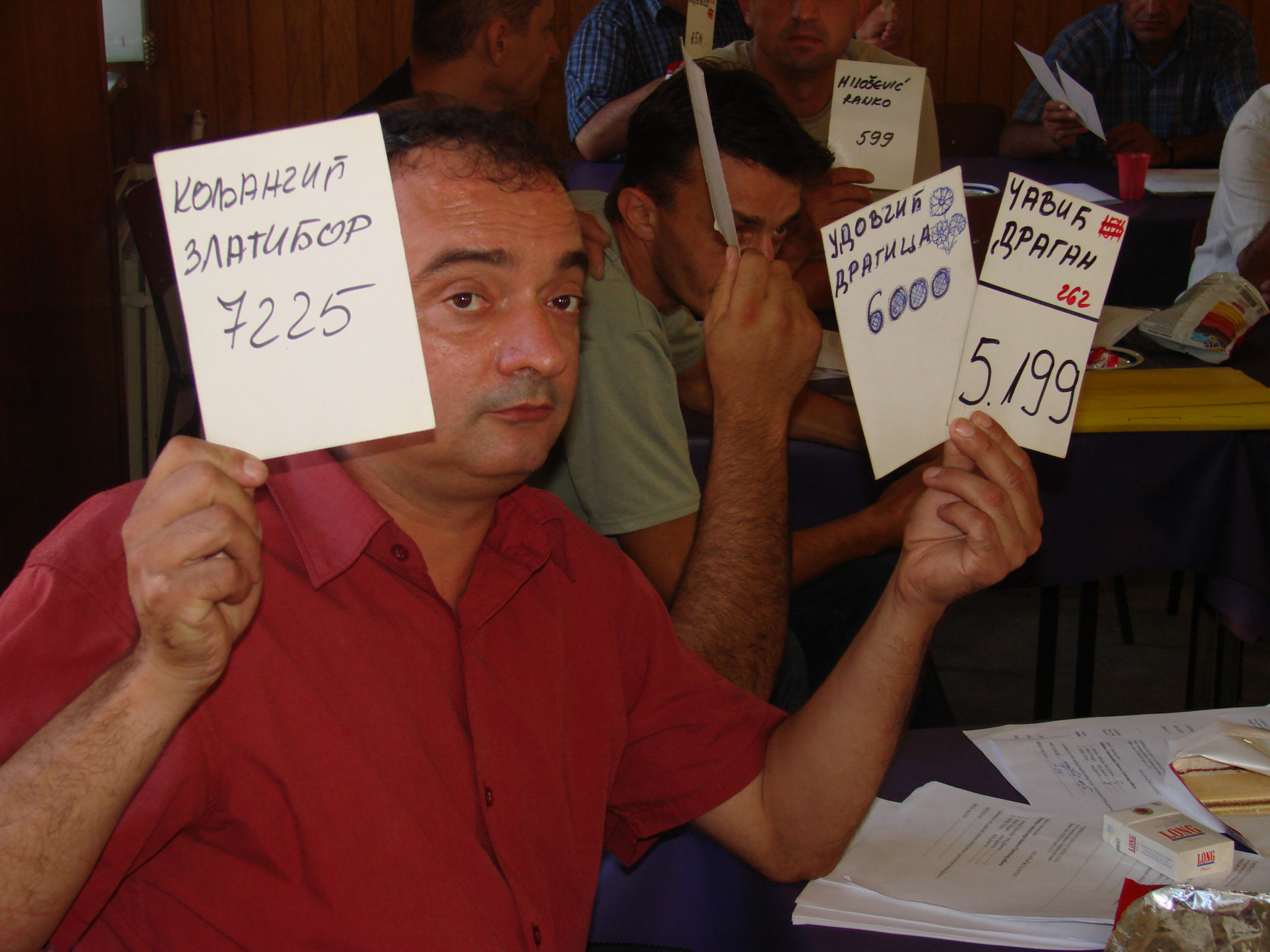

President of the factory’s minority shareholders Zlatibor Koljačić said that Antonić funneled the capital from the factory.

He added that Antonić told him once that the land on which the factory was located was ideal for a new business center: ‘We believe that his aim was to paralyze the factory.’

The factory owns nearly 23,000 square meters of land. According to the RS Tax Administration, the market value of a plot in this part of town is 650 KM per square meter, which computes to 15 million KM for the factory’s land.

The factory’s estate borders on the new headquarters of the RS government.