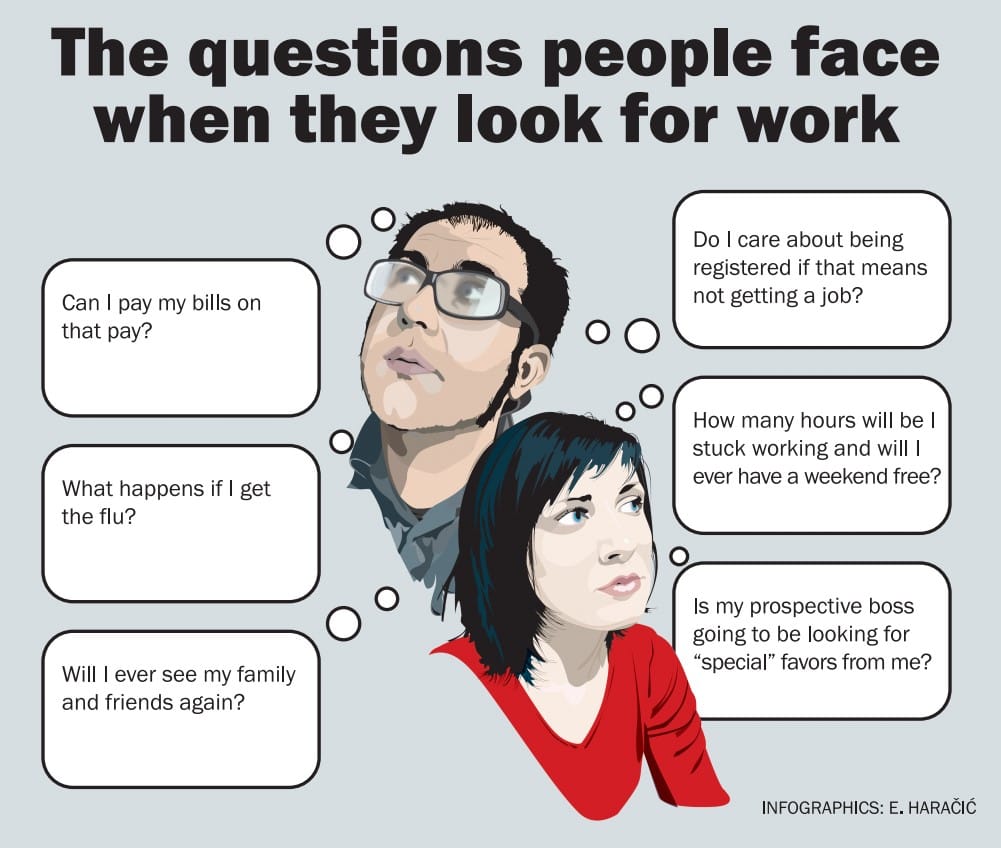

Looking for a job in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is a lot like buying a lottery ticket, say young job seekers, with all the odds in favor of employers.

Positions are scarce and competition is heavy with youth unemployment at about 50 percent according to the World Bank. To win a job you must be willing to conform to employers’ vision of the perfect worker and to give up on such basic benefits as a 40-hour workweek, overtime and contributions to health insurance and pensions.

That is what reporters for the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) found this fall when they set out to experience what it is like to be untried, unconnected and unemployed in the BiH capital.

CIN reporters responded to online and printed ads offering jobs that did not require specialized skills or qualifications. They applied to become a baker, a car washer, waiter and waitresses, a laborer, a salesman and a receptionist. They did not lie about qualifications, but did not give their current employment. They pressed for information about rights and benefits. One reporter ended up being offered a waitressing job.

A CIN survey done by Prism Research of 1,550 people in December showed that respondents between 18 and 35 report working or having worked unregistered more than any other age group. More than 20 percent said they had worked in the labor black market, with another 19 percent saying they were unwilling to answer the survey question.

The perfect job candidate

Some dozen men and women including one CIN reporter, lined up recently under a leaden sky at the café-discotheque Sa-club, hoping to snag a waiting job. Most, in their early 20s saw the disco job as potentially fun work with big tips.

They were led into the darkened cafe, where with subdued music in the background, a young waiter told then what to expect: 400 KM a month, which he described as a realistic salary in comparison to places that promised waiters high incomes. He talked about shifts and getting along with customers, and then asked for questions. The CIN reporter had one –what about pension and health insurance?

The waiter said no, pension and health insurance were not covered, but that if the business ‘develops well’, nothing was out of the question, even higher salaries.

There are no further questions about worker rights. The candidates introduced themselves, talked about their experience in restaurants and that was it.

The reporter did not get an offer

In an interview later, club owner Semir Redžepović said he worked in accordance with regulations and had passed review by labor inspectors.

At Barsa in Hrasno, the same reporter interviewed for a waiter’s job. That interview ended quickly when the reporter admitted he had no experience, but was a quick learner.

The interviewer smiled at such naïve questions about pay and insurance. The pay was the ‘standard’ 350 KM cafes give and as for other benefits: ‘No, you know that in cafes they don’t register.’

Elzana Mašović, the bar manager, said later that workers there were registered; she had just told the job applicant differently to get rid of a candidate she did not think was serious about the job.

CIN reporters found that to be the case for many jobs. ‘What if you don’t like it here, and I had you registered?’ the owner of a quick-food kiosk in Dobrinja, responded when asked about registration of workers.

In various interviews reporters were asked about where they lived, their marital and family plans, how many unemployed family members they had and other personal questions.

One CIN reporter never got so far as an interview when she responded to an ad in a daily newspaper from the club Incognito looking for a “younger girl” to tend bar.

What is a younger girl, the reporter asked. ‘Well younger’ the waitress handling the call said. ‘I don’t know what to tell you. A younger girl. How old are you?’

‘Forty-three’ said the reporter.

‘Aaah’ said the waitress. When pressed to explain why the job had to go to a younger worker, she explained. ‘She’s quicker.’

A 29-year-old reporter answered an ad from the Galija pizzeria which was looking for two girls who speak English to work in the dining room. She fared no better.

She was ‘a woman with obligations’ she was told, a husband and baby.

The boss explained that unattached women were the best hires. He also looks for workers who are communicative, not too young, under 18, but not too old; not too skinny because the job is hard, but not too fat either, because they can’t handle the stairs.

His waitresses work six days a week in two shifts from 8 to 3 or 3 to midnight with no holidays. They get 10-days of annual leave, but calling in sick is a problem unless they can find a substitute. They are registered for four hours and get a “standard” salary of 350 to 400 KM plus tips and health insurance is paid.

Owner Almir Karaman said he did not offer a four-hour registration for eight hours of work. ‘You are asking questions like you are an inspector’ he said, adding that if CIN knew of any job candidates send them to him. They’d be registered, he promised.

Bono pizzeria was offering 400 KM with a chance to be registered after three months if your work was good. The restaurant runs two shifts from 6:30 to 3 and from 3 to 11 and waitresses get a day off every, two weeks. If you get sick or have family problems you have to find a stand-in.

In an interview with CIN, the pizzeria owner said there was no other responsible way to deal with registration but to first wait to see if a new employee was going to stay on the job.

Azra Šehbajraktarević president of the retail union in BiH, said it was common for shop owners to demand long hours from staff who are frequently unregistered and young workers. While the law requires 40 hours of work over six days, the typical retail job requires 12 hours of work a day. If a worker complains or refuses to work, she said, there are plenty of unemployed people to take her spot.

The owners of pizzerias and shops say they have invested their savings and cannot let their businesses fail. The businessmen CIN reporters met in their experiment were trying to make it – and they ask workers to share the burden.

Tales of job-seekers

While looking for work, reporters met bona fide first-job seekers.

Armin Varešanović, 23, from Sarajevo has been searching for a steady job for three years. He started out optimistic when he finished medical high school in Bjelave with the title sanitary-ecological technician. Professors told the students they would find jobs for 3,000 KM, because theirs was a new line of study. He thought he was on his way during a 6-month internship in a clinic in Ilidža, but when the internship ended there was no job offer.

He sold CD’s and gave out business cards in cafes until he heard about a waiter getting sacked in a cafe near the Skenderija.

‘During the interview, I didn’t ask even about salary, and I never mentioned insurance because I know the practice of not registering workers there. It would be seen as provocation and that they will tell me ‘Go, get lost now,’’ he said.

After a couple of days of working on probation, he began earning 10 KM a day. He did some pizza deliveries too and figured he was ‘doing good.’

‘Nobody asked me about contributions and registration, nor did I ask myself why it isn’t paid. I knew that it was simply practice. Why should I tell him, when I know it isn’t worth his while to register me?’ he said.

A few weeks after he started he was fired along with a cook, he says, when the boss noticed a hair on a plate. Now unemployed, he is looking again and ready to work unregistered for any money.

Emina Drljo, 24, a Serbian student in Sarajevo, has worked more than 20 waitressing jobs over the past year and has never been registered.

‘I had no choice’ she said, ‘one has to pay bills and my parents can’t give me much. Although I never wanted to be a waitress, working in catering creates an impression that you can’t do anything else and you lose your will.’

Drljo thinks that young girls in unregistered jobs have it worse than men. Owners treat them as someone who should show their gratitude for being hired in a more ‘personal’ way. One married boss suggested she ‘hang out’ with him. ‘It was all wrapped in talk about how rich is he, how she knows what men want etc. I got up and left as soon as he started talking about it’ she said.

Another owner commented on her appearance and offered to let her sleep in his cafe. Drljo said she stayed long enough to get some salary for rent. In order to prevent staying alone with the owner in late shifts, she invited friends in every night. ‘Those three days with him were like three years’ she said.

‘After everything’ she said. ‘I just want to finish school and get a normal job.’