In the fall of 2010, a 16-year-old girl walking home near Brčko was offered a ride by an acquaintance. He drove her not home but in another direction where he touched her and tried to kiss her. She managed to run away.

Three years later, the Basic Court in Brčko District ordered that her assailant pay the girl 5,000 KM in compensation for the mental anguish he caused. Appeal Court judges decreased that to 3,000 KM.

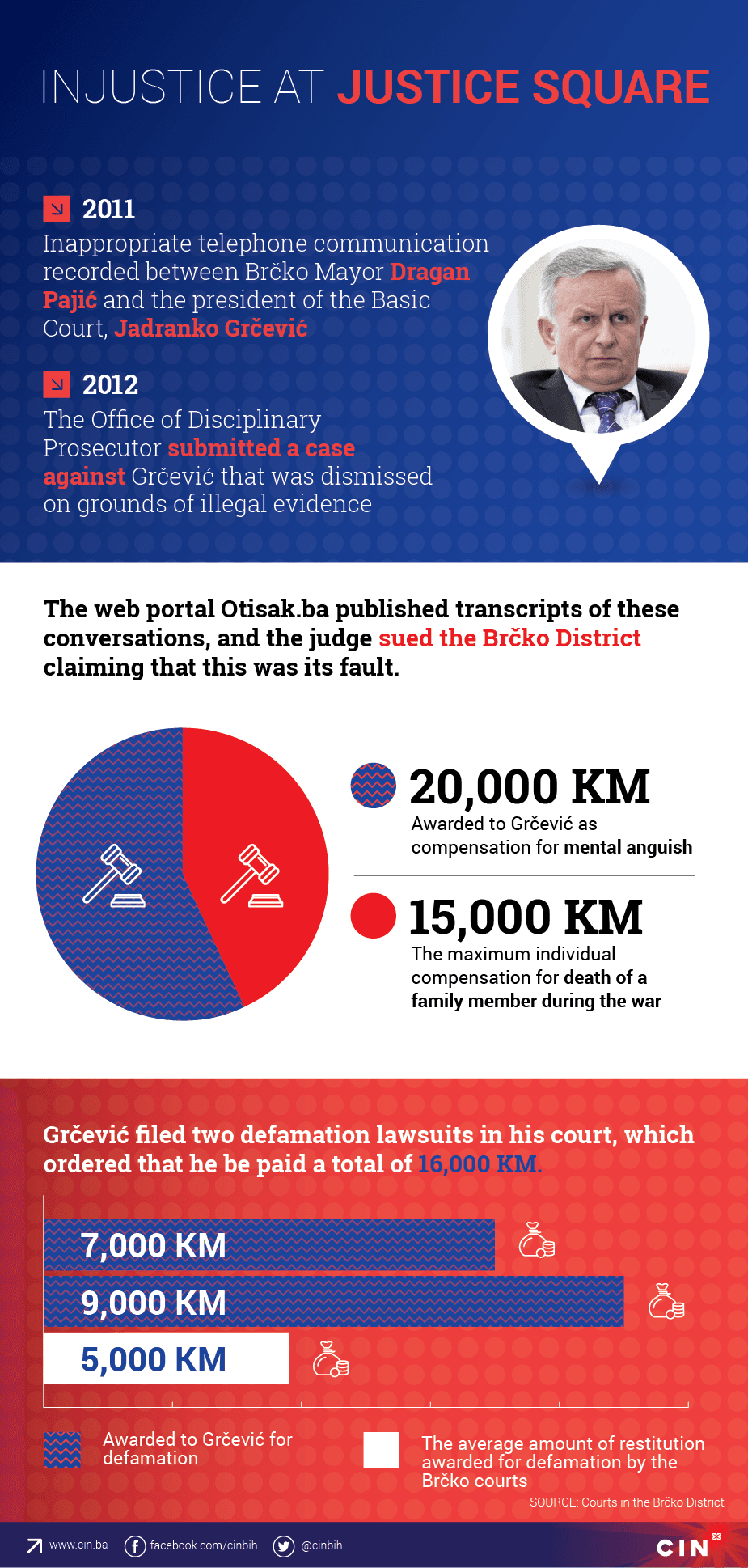

In contrast the judges saw the need for a much higher compensation for their boss — Basic Court of Brčko District President Jadranko Grčević. For injury to his honor, reputation and dignity he received compensation of 36,000 KM in three cases.

In the first, he received 20,000 KM for damages he suffered after his private conversations with the mayor Dragan Pajić on official matters were published in full by a local web portal. According to court records available to the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN), this is the largest compensation for injury to honor, reputation and dignity handed out in Brčko in six years.

Grčević told CIN reporters that he was right to ask for so much. “I don’t see why I would be squeamish about it…,” he said. “If someone is going after the president of the court and is ordered to pay 2,000 KM as compensation, or 3-to-4,000 KM, then they will go after me every day.”

Grčević appeared before the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council on account of his conversations with the mayor and other officials, but he was never sanctioned because the evidence against him was judged not legal.

Apart from restitution for the publication of his conversations, the courts also ruled that he be compensated in two defamation cases totaling 16,000 KM.

Grčević has presided over the Basic Court in the Brčko District since its inception 16 years ago.

The Court’s President in the BINGO Operation

The District’s judicial institutions are located at the Brčko’s Justice Square. When in 2011, District prosecutors asked the police to surreptitiously record Mayor Pajić’s conversations because they suspected him of abuse of office, they had no idea Grčević would show up in their investigation as one of his confidants. The police code-named the operation BINGO.

“Pal, they are sacking me and you’re not answering (my phone calls),“ Pajić groaned to Grčević at the beginning of a conversation recorded May 18, 2011. The following day, the Brčko assembly legislators were discussing the termination of the mayor after the Central Election Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) established that his mother’s firm won a contract from the District. The mayor and the judge conversed about the balance of political powers and outvoting in the Assembly.

“They have all the Bosniaks and that Bogićević and Staka…Now we think that it is, now that it isn’t. We’re not sure if they have Niko Babić.” Pajić talked about Grčević’s friend, legislator Babić. The following morning, on the day he was to take part in the vote on the termination of the mayor, Babić was summoned to the Court’s president’s office. Grčević told him about the conversation with Pajić.

“But, what’s my role in it? What have I done? Did Niko change his opinion? He did not. Isn’t that right? Could I have returned Niko from the doors and tell him, ‘Hey, Niko, go to your home now. I don’t want to listen to that,’” Grčević told CIN reporters.

Grčević informed Pajić about Babić’s visit. The same day the mayor was fired for conflict of interest.

In intercepted telephone conversations, Grčević also talked about cases before the Court. He asked Miron Bura, former director of the Office for Managing Public Property for Brčko, to receive a friend of his mother’s and talk to her about compensation for expropriated land.

Grčević said he doesn’t care about being secretly taped. “To this day I’m not interested in who’s being tapped. I behave freely.”

In October 2011, police arrested seven District employees, among them Pajić and Bura. Soon after, Grčević publicly clashed with the head of the Brčko police force Goran Lujić. In April 2012, the Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor submitted to the Council a case against Grčević for talking to the media inappropriately about ongoing cases being conducted by the Prosecutor’s Office and police and also because he discussed his termination and votes by Assembly members with the mayor. The meeting with legislator Babić on behalf of Pajić to discuss the mayor’s termination also was questioned. The case accused Grčević of inappropriately informing Pajić and Bura about cases before the Basic Court.

Officials from the Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor thought that Grčević had harmed the dignity of justice office and endangered public confidence in the impartiality and credibility of the judiciary. Disciplinary prosecutor Arben Murtezić called on the Council to sanction Grčević.

Grčević did not deny talking with Pajić and Bura, but insisted that the prosecutors had not obtained evidence against him legally. The Council’s first-level disciplinary commission agreed and concluded that he had been illegally tapped. The commission acquitted him of all charges related to his conversations with Pajić, Bura and Babić.

“Maybe I was a bit careless, but, how should I put it, I did not think much of it. I thought that this was incidental. Do you understand me? What do I have to do with solving some issues surrounding the mayor,” Grčević told CIN.

He received a written warning, but it was not published in public and it is the mildest sanction for a judge who has committed a disciplinary misdemeanor. The Office of the Disciplinary Prosecutor appealed the decision, but the second-level Council’s disciplinary panel did not uphold it. Instead of being served a secret written warning, he was publically reprimanded.

The Code of Judicial Conduct states that a judge should not have inappropriate liaisons within the legislative and executive branches and that the public should have a view that such liaisons or influences do not exist. Grčević said that he did not violate the Code: “Someone had interests in seeing me out of the office.”

Grčević told CIN that he got wind that this was the strategy of the Chief Prosecutor Zekerija Mujkanović and the former Police chief Goran Lujić. Grčević told CIN reporters that the chief prosecutor copied the secret recordings for the Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor because he was on good terms with Lujić.

In November 2014, the Council’s members voted in Grčević for the third time for the president of the Basic Court.

Goran Nezirović, the Federation of BiH Supreme Court judge and a member of the Council, was on the second-degree panel that decided on Grčević’s case.

Asked if the Council took into account that the citizens of Brčko heard surreptitiously recorded conversations when it deliberated the appointment of Grčević, Nezirović replied: “Of course the panel would take into account things like that. However, we cannot make decisions based on hearsay evidence. In other words, it really has to be established on someone’s accountability, that someone is undeserving, in order for that person not to be appointed in judiciary. As far as peer Grčević, such findings were not found nor were there binding sanctions or trials at the time”.

In early 2013, the Brčko Prosecutor’s Office accused former mayor Pajić of using his office to get civil servants in public and government agencies to rig a bid for construction and furnishing of a new Gynecology Department building for the General Hospital in order to help an Austrian firm, Vamed, win it. Pajić was also accused of asking government employees to hire two candidates in a middle school and art gallery without regard to their qualification. And he was accused of ordering official district drivers to take his son and wife to Belgrade and Vienna.

Pajić was tried before the Basic Court in Brčko. Even though the Prosecutor’s Office had known about the liaisons between the defendant and the Court’s president, it could not have asked for the case to be transferred to another court, because the Basic Court holds jurisdiction over these type of offences.

“It is not heartening to hear during investigation that the court’s president, who will be in charge of the trial, tells the main suspect at that moment certainly indicted, such words of support. What can I say, during the exchange it was hinted that ‘you should know – I’m still your pal, your friend, my opinion has not changed’ and so on and so forth”, said prosecutor Mujkanović.

In 2016, Pajić reached a deal with the Prosecutor’s Office and was sentenced to one month in prison. He swapped that punishment for a fine and paid 3,000 KM for freedom.

Anguish and Restitution for Published Conversations

In February 2013, after Council closed disciplinary proceedings against Grčević, a reporter from the Brčko web portal Otisak.ba Edin Ražanica published transcripts of the intercepted conversations between Grčević and the mayor.

He thought it was important for the public to know about the Court’s president behavior. The judge sued the District in the court that he chaired — reasoning that negligent authorities had allowed publication of the records. He demanded 50,000 KM in restitution.

“This is my subjective opinion and I may ask for hundred thousand (KM),” said Grčević.

The trial was closed to the public and Justice Faruk Latifović ruled in Grčevićev’s favor. He did not want to speak to CIN about his work on the case.

Grčević said that he did not tell the justice how to decide his case. “I might communicate the least with Latifović. The man lives in Tuzla; he’s a young judge,” said Grčević. “He would not be swayed, not only in this case, but in other cases as well. “

The Attorney General’s office that represented the District appealed and the case went before the higher court. The Appeal Court established that 50,000 KM compensation was not in line with case law of other courts in BiH and the region and decreased it to 20,000 KM.

Even thus decreased, the compensation awarded to Grčević is the highest compensation Brčko courts have handed out in the past six years for an injury to a person’s honor, reputation and dignity.

The restitution ordered for Grčević is even higher than judges have given families of war victims for mental anguish and suffering. In the spring of 1992, Hazim Vilić was taken from his house in Brezovo Polje. His son Fadil found out from a neighbor that his father had been killed, but never found his body. After the war, Hazim was declared dead, and Fadil demanded compensation from the Republika Srpska. The basic court and the Court of Appeal in Brčko awarded 15,000 KM as restitution to him for the death of his father.

Like Grčević, Pajić also sued the district in Basic Court, asking for 20,000 KM compensation for mental anguish he suffered after his private phone calls were disclosed. That case is ongoing.

Trial at the President’s Court

Grčević also sued Ražanica for defamation because of the Otisak.ba stories. This case was also tried before the Basic Court, which ruled that the reporter had injured Grčević’s honor and dignity in referring to him as an ethically compromised president who does not do his job under the law.

“Mr. Ražanica should bear in mind that I have a legal right to sue and that I’m not a man, how can I put it, an average man, that I serve in office,” Grčević told CIN.

The court ruled and the Appeals Court agreed for Grčević, and Ražanica must pay him 7,000 KM.

“It is neither pleasant nor appropriate that I am sentenced by the court where the court’s president sued me. It is not!” Ražanica told CIN.

Osman Mulahalilović, Ražanica’s lawyer, asked the Basic Court to disqualify the judges subordinate to Grčević from this case. His motion was dismissed.

He said he finds it unacceptable that the court presided over by Grčević is deliberating in his cases. “Any impartial observer, an objective impartial observer, could come to a conclusion that the trial will not be fair.”

Justice Nezirović said that a judge is never tried before his or her court, but before another one. He said that because of the Constitution and the laws, in some cases, like in Brčko, this was not possible.

Grčević has sued others before the court over which he presides. He sued Salih Fazlić, who filed a criminal complaint against him and his colleague justice Dragan Tomaš.

Fazlić reported Grčević and Tomaš for forging official documents and abuse of office in order to take property from his father. Apart from the Prosecutor’s Office and police, Fazlić sent the criminal complaint to 13 addresses including five media outlets. The web portal Otisak.ba published the complaint in full.

Tomaš and Grčević sued Fazlić for defamation and demanded restitution for mental anguish that the publishing of the complaint caused them. The court ruled in their favor and ordered they each be given 9,000 KM. The Appeal Court upheld this ruling.

According to the rulings collected by CIN, the Appeal Court in Brčko has just once awarded 10,000 KM compensation for defamation. In that case, a daily published pornographic material, incorrectly stating that a female civil servant from the District’s government was in it.

No other defamation case in the past six years has called for compensation of more than to 6,000 KM. After he lost the case with Grčević, Ražanica complained to the Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor about the amount of restitution.

This is one of 54 complaints against Grčević to go to the Office. Only two have resulted in disciplinary proceedings. The Office continues working on another nine complaints.

Grčević, the only judge who has presided over the Basic Court in Brčko since its inception in 2001, has not decided if he will run again when his current term runs out in November 2018.