When institutions responsible for food safety in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIH) learn that a potentially dangerous food has appeared on the market, it can take three to 13 days for the problematic product to be located and removed from stores.

That is often long enough for bad products to be sold out and citizens’ health to be endangered.

Since 1979, a European system has sounded alerts about dangerous foodstuffs entering the market. Thirty nations belong to The Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF), but it shares information globally and with all countries that might be affected, including non-members.

BiH is not yet a member but has gotten alerts since the BiH Food Safety Agency was established in 2006. Citizens can really only benefit, however, when institutions can react quickly to alerts.

A recent example of oil released from reserve supplies demonstrates that BiH institutions cannot do that.

On Dec. 13, 2007, the Federation of BiH (FBiH) government released oil from its Reserves Authority in an attempt to boost supply and keep down dramatically rising food prices.

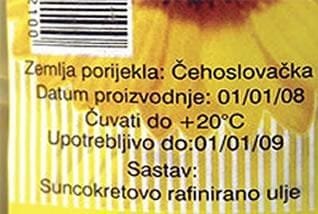

But that day, consumers were shocked by labels on bottles of this oil that identified it as sunflower oil produced Jan. 1, 2008, in Czechoslovakia – a date that was in the future, not the past, in a country that went out of existence 15 years ago.

Consumers realized that the labels had to be bogus and suspected the oil inside might be also. Some complained to the Sarajevo newspaper Oslobođenje, which did a story. On Dec. 18, a state lab analysis showed that the bottles actually contained rapeseed, not sunflower oil. It was not until Dec. 19 that an order was issued to remove the oil from sale.

But seven days later ‘Sunce’ oil apparently was still being sold. On Dec. 26 FBiH inspectors again requested urgent information from the reserves agency about what supermarkets it had delivered oil to so that it could be removed.

The FBiH government removed Reserves Director Hrvoje Dragoje and FBiH Financial Police and Sarajevo Canton Prosecutor’s Office are pressing charges of corruption in the oil fiasco.

Sluggish Information flow

RASFF information about harmful products in the market goes to the BiH Food Safety Agency. A relatively new state institution, it started operations only in June 2006, when Director Sejad Mačkić was appointed.

The agency is still not at full capacity. Of 49 intended workers, only 25 are hired. Mačkić points out the agency enjoys good cooperation with the entities’ inspectors and ministries of health, even though it has authority only to issue recommendations.

When it gets information about potentially dangerous food, the agency evaluates the risk and makes suggestions to inspection authorities in the FBiH, the Republika Srpska (RS) and the Brčko District.

In the RS, inspections are divided between entity level which controls imports and municipal level which has authority over the interior. In the FBiH, inspectors control imports coming in over borders while cantonal and municipal inspectorates are in charge of inspections within the entity.

‘When it is necessary to remove some product en masse, then the system doesn’t function’ said Ljubo Janjić, executive director of the Association for Consumer Protection “Plava Sfera.’ He said, ‘We also had a case of tin cans from Rovinj, and it took 15 days to withdraw them.’

RS Chief Sanitation Inspector Desimir Miljić said that the speed of product withdrawal from the market is problematic and lags behind other countries. ‘We don’t have that rapid system for alerting’ he said. ‘That process is pretty slow here.’

The FBiH chief sanitary inspector, Nijaz Uzunović, in contrast, is happy with how fast unhealthy foodstuffs are withdrawn. He said he forwards recommendations from the BiH Food Safety Agency to cantonal and municipal inspectors the same day he gets them, or at the latest, by the next day, and inspectors get out in the field very quickly.

Documents that the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) obtained indicate that the process is not that fast.

For example, on Feb. 14, state agency notified Uzunović that dry figs imported from Hungary were contaminated with dead insects and their excrement. He forwarded the notification to cantonal and municipal inspectors two days later. Eight days later, Uzunović told the state agency that the bad figs had been withdrawn from the market in four of 10 cantons.

Uzunović wrote state food officials Feb. 22 that, ‘You will get the complete information when sanitation inspectors from all cantons submit a written report about surveys undertaken in their canton.’

Uzunović said he has no control over cantonal and municipal inspectors. ‘Whether they do all that within two-three days or within five-six days, it also depends on the urgency, involvement and, of course, on the number of inspectors and if they can make it’ he said.

Uzunović maintained that, nonetheless, tainted food is removed from shelves in about the same time as in other European countries.

Joechen Heimberg, head of public relations for the German Federal Ministry for Consumer Protection and Food Safety, said that every state in his country, as in BiH, also is responsible for markets – but they need just 12 and 48 hours to pull dangerous food out of the reach of customers.

In a recent incident, Bulgarian authorities managed to pull contaminated meat out of stores less than 24 hours after it was discovered. They also stopped further production at the factory that was turning out the bad product, according to Mariela Pchelinska, a spokeswoman for the Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

Building a system

Food safety is a new operation in BiH.

The BiH Food Safety Agency and the Agency for Market Oversight have been operational for less than two years. Most local food safety legislation dates to the 1970s and ‘80s and is outdated.

State officials have drafted a bill on regulation of genetically modified food and a number of rulebooks are waiting to be vetted by the Council of Ministers and passed by the BiH Parliament.

The system for fast removal of unsafe food is yet to be built, but advances are being made, the experts say. They say that pressure from consumers and non-governmental organizations would help in bringing more market checks and attention to food safety.

‘The best way for citizens to get to know more about this is to have them check themselves’ said Janjić, the consumer protection advocate.

Mačkić of the BiH Food Safety Agency said that consumers must become more wary about their food. ‘When people buy clothes they regularly read labels carefully to see which type of materials it contains, but when buying food they are less cautious.’

He would like to see consumers suing when they suffer food poisoning instead of just relying on government to act. That would help make sure that guilty companies are punished and others are warned to be more careful about what they are producing and distributing.

Mačkić said consumers should routinely ask for and keep receipts for food they buy. These provide evidence in court for lawsuits.