Judge Atko Huseinbašić refused for years to work on cases. High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council (HJPC) would sanction him, but not remove him from office. He continued to commit infractions.

The Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor tracked down dozens of cases in which he committed infractions: he failed to issue timely rulings and he let the statute of limitations expire. The office initiated disciplinary proceedings against him five times.

In 2014, after the third proceedings, HJPC transferred Huseinbašić from Basic Court in Banja Luka to Basic Court in Teslić. He continued to make mistakes in his new court. Finally, in 2019, the HJPC removed him from office.

Despite sanctions, Huseinbašić does not think that he’s to blame. He told reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) that he did everything perfectly.

“Judge Atko absolutely makes no mistakes,” said Huseinbašić. “What the High Judicial Council imagines has absolutely never happened.”

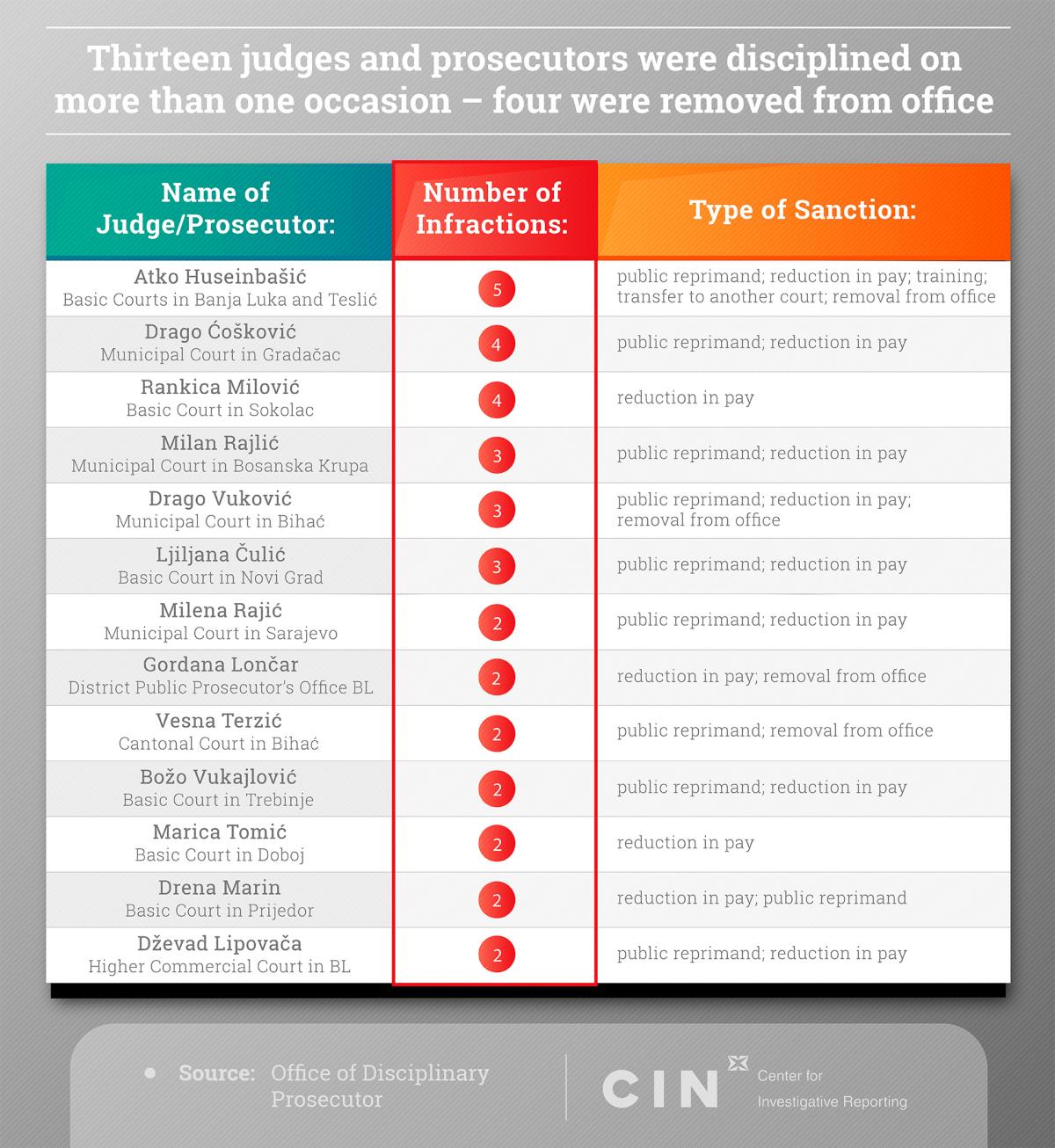

Over the past nine years, HJPC’s disciplinary commissions meted out around 200 disciplinary sanctions to judges, prosecutors and expert assistants because they did not do their work responsibly. CIN reporters found that 13 had more than one sanction.

Huseinbašić’s example shows that punishment does not always make judges and prosecutors act more responsibly. Some of those disciplined because of bad performance were later charged with criminal offenses.

HJPC’s members say that they don’t have a better way of overseeing the work of judges and prosecutors. They also say that they have not analyzed cases of those who committed infractions after being sanctioned.

Sanctions Without Effect

Four months after he was removed from office, Huseinbašić agreed to talk with CIN reporters.

“I was preaching law here in Republika Srpska.“ said Huseinbašić.

During two and half hours, this former attorney and judge talked about more than 30 years of his career and the trials that got him sanctioned. He also talked about his colleagues. He said that he has a spotless record and he kept calling his fellow judges and prosecutors names.

Nevertheless, HJPC proceedings tell a different story. Disciplinary commissions investigated Huseinbašić as many as five times.

During 2006, Gostimir Marinković, a co-owner of private firm Šel-Pan from Laktaši was on trial before Basic Court in Banja Luka on tax evasion charges. The court found him guilty of not paying taxes for gasoline he sold and was sentenced to three months in prison.

However, Huseinbašić wrote a verdict after nearly two years when the statute of limitations in the case had expired. During the disciplinary proceedings, Huseinbašić defended himself by saying that he was overburdened and that Marinković paid for his conviction despite the expired statute.

Yet, the members of HJPC’s disciplinary commission called the judge’s behavior irresponsible and punished him with a 10 percent reduction in pay over six months. During the disciplinary proceedings, it was also revealed that Huseinbašić was 10 months late in writing a verdict with which he was to acquit a group of customs officers charged with slapping lower duties on goods imported by some firms.

Just several months later, Huseinbašić found himself again before a disciplinary commission because he did not work on a case. However, he got off easy — with a public reprimand.

Huseinbašić cannot recall details from these cases, but he thinks that prosecutors should more quickly file indictments so that the statute of limitations would not expire.

Vitomir Soldat, former chief prosecutor of District Prosecutor’s Office in Banja Luka, said that some prosecutors complained about Huseinbašić’s work so he brought this up with the Court’s president.

“It’s not the prosecutor’s office which conducts proceedings. The cases expired after indictments had been filed, not during the investigation or before it,” said Soldat. “Really, this is not worth commenting.”

In 2014, the Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor conducted new proceedings against Huseinbašić. They revealed 11 cases in which he failed to issue verdicts even for as long as six years. Among those who have been waiting for years for his verdicts were persons accused of illegal weapons’ production, car thievery, and drug sales. Some of them had already had a criminal record.

“These offenses are absolutely marginal,” said Huseinbašić. He added that he intentionally did not want to work on these cases in order to force the court’s leadership to talk about “serious issues”.

HJPC Vice President Ružica Jukić was on one of disciplinary commissions deciding on his case. She said that Huseinbašić told the commission members that he was not going to write verdicts. This time both disciplinary commissions sanctioned him most strictly – they removed him from office.

However, Huseinbašić complained to HJPC and its members upheld his complaint saying that dismissal was too harsh. They argued that the commissions did not take into account the respectable results of his work.

Instead of removal, HJPC moved him to the Basic Court in Teslić with a 20 percent reduction in pay over six months. Jukić said that transfer of a judge to another court served no purpose.

“That punishment exists, but in my opinion it was not adequate because it was known that the same thing would be repeated,” said Jukić.

New Court, Old Infractions

After this punishment, another two disciplinary proceedings were held against Huseinbašić. In one, he was sanctioned for not issuing timely decisions in cases before the Basic Court in Banja Luka, while in another infraction he committed at new work – in court in Teslić — were revealed.

In the fall of 2016, BiH media outlets published photos of a young man, Bogdan Rakić, lying in a pool of blood on his bed. He was beaten and harassed on Borje Mountain, according to news articles. Armin Jašarević and Branko Jurić were charged with harassment and torture and Huseinbašić was on the panel of judges deciding their sentence.

The judge again committed an infraction. In February 2017, Huseinbašić released the two men after they paid a bail worth 6,000 KM. In his ruling he stated that he made this decision together with the other two judges, which was not true. This decision was not valid and another court nullified it.

Huseinbašić said that what the commissions did was not right and that his colleagues from the court panel in Teslić lied.

Huseinbašić appealed his transfer to Teslić to the BiH Constitutional Court. The court established that disciplinary proceedings were belated and his appeal was upheld. In 2017, he was sent back to Banja Luka.

However, infractions continued. The Office of Disciplinary Prosecutor initiated a fifth proceeding against Huseinbašić for his bad performance in Teslić and Banja Luka. It was revealed that he issued an illicit ruling on bail for Jašarević and Jurić, and that he did not work on 36 cases. In the Banja Luka court, he refused to work on misdemeanor cases. The disciplinary prosecutor again asked that the judge be removed from office. Both commissions approved it.

Finally, HJPC members supported this decision. They said that the judge refused to do his job and removal from office was the only adequate punishment. Thus, after eight years, 56 infractions and five disciplinary proceedings, HJPC banned Huseinbašić from work as a judge.

“You may have as many proceedings as you like, but I am three leagues ahead in my thinking from any other judge,” said Huseinbašić.

Selim Karamehić, an HJPC member who was on a Huseinbašić’s disciplinary commission, said commission members took into account that the judge was sanctioned several times.

“The council cannot allow one and the same disciplinary infraction, especially the gravest and serious infractions, to be repeated over and over again,” said Karamehić.

His HJPC colleague Goran Nezirović said that Huseinbašić had good work results but he was drawing attention to work irregularities in a wrong manner.

“He was fighting the system and its deviations, as he sees them, and his form of protest was not to write verdicts,” said Nezirović. “First time when he was sanctioned — I don’t say that he did not deserve to be removed back then as well, but he was given another chance,” said Nezirović.

Huseinbašić said that he was going to appeal HJPC’s decision with Constitutional Court.

From Disciplinary Sanction to Indictment

Records CIN reporters collected show that at least another 12 judges and prosecutors were sanctioned more than once. Some were punished even three or four times. Three were removed from office while others continued to work in the justice system.

HJPC members say that they have not analyzed these cases so far. Jukić said that those repeating infractions should be more harshly sanctioned: “If you were sanctioned once, I think that the second time there should be no more mercy.”

Her colleague Karamehić said that the number of those who repeated infractions was not high: “This means that all those sanctions which we meted out had affect to sober judges and prosecutors up, to make them more conscientious in their work.”

Disciplinary punishments were not sufficient to get some judges and prosecutors to do their job more responsibly. Prosecutor’s Offices have even initiated criminal investigations against some of them.

In 2011, judge Milena Rajić of Municipal Court in Sarajevo found herself before disciplinary commissions. She was publicly reprimanded because she had not been issuing timely rulings. However, in 2018, she was sanctioned for the same thing. Salim Bilalović complained about Rajić’s work. He learned that Rajić issued a decision which left him and his family members without a plot of land in a Sarajevo borough of Ilidža. The plot of around 600 square meters, he said, belonged to his grandmother Zlatka Bilalović.

A disciplinary commission established that the judge issued a ruling without sending the lawsuit to the defendants so that they could respond to it. Such judgement benefited Suvad Hajdarević who got a title to the land.

The commissions disciplined Rajić with a 30 percent reduction in pay over eight months.

The Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office in Sarajevo investigated this case and found that the signatures of Zlatka Bilalović and other defendants were forged.

Because of this and other cases in which she illicitly issued decisions, Rajić is currently on trial before the Cantonal Court in Sarajevo. She refused to speak to CIN reporters.

Judge Drago Ćošković of the Municipal Court in Gradačac was sanctioned four times. Some of the defendants in cases over which he presided had to wait for him to write a verdict for more than a year. On some cases he did not work for as many as ten years.

Tuzla resident Melbat Mujezinović was one of those awaiting Ćošković’s ruling. It took three years for the judge to decide if Mujezinović is entitled to restitution following a traffic accident in which he received injuries. The trial ended in April 2014, but the judge wrote a verdict only 21 months later.

Mujezinović complained to the BiH Constitutional Court about the judge’s performance. The court decided that three years to solve the case was an unreasonably long period. The Constitutional Court ordered the government of Tuzla Canton to pay 450 KM indemnity to Mujezinović.

Even though he’s been committing infractions for years, the harshest sanction he received was a 20 percent reduction in pay over six months. Every time Ćošković pleaded guilty. He did not want to respond to reporters’ phone calls, while the president of Gradačac court, Slobodanka Kojić, did not want to comment on her colleagues’ infractions.

Deputy chief disciplinary prosecutor Mirza Hadžiomerović said that it was sometimes frustrating to conduct proceedings against persons who had already been sanctioned. He did not think that someone should be removed from office on account of the number of disciplinary proceedings held against them.

“But I think that it is a truly important circumstance to be taken into account, especially when one and the same disciplinary infractions are at play,” said Hadžiomerović.