In 2013, the general manager of General Hospital in Sarajevo, Sebija Izetbegović, hosted together with Emir Talirević, the owner of a privately-owned health care provider My Clinic, a free-of-charge diagnostic tests for heart and Alzheimer’s for the general public. These promotional events were a harbinger of things to come – the business collaboration between two managers.

From then on they wasted no time.

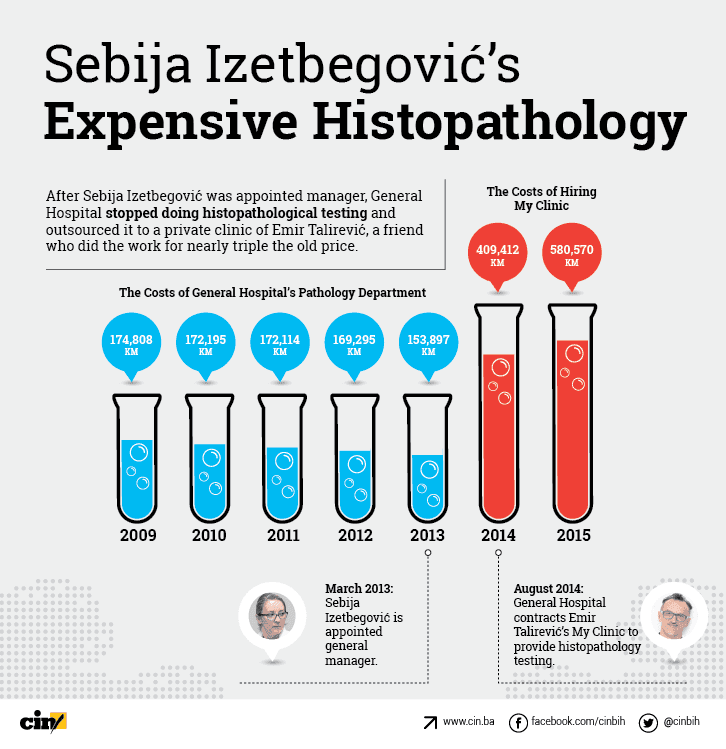

When in 2013, Izetbegović was appointed general manager in the hospital named after Prim. Dr. Abdulah Nakaš, she was left without a pathologist. Next August, Izetbegović outsourced testing of biopsy and surgical specimens to Talirević’s My Clinic for a price several times higher than the hospital had previously paid.

Talirević said that his long-term friendship with the General Hospital’s manager did not help him get the job.

“The professor and I know one another very well. She’s an excellent manager…This is precisely why we made big financial concessions to the General Hospital,” Talirević told the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN).

Records CIN has obtained paint a different picture. Before joining forces with Talirević, histopathology cost the hospital on average 168,000 KM a year. After it signed a contract with My Clinic, the hospital paid about 550,000 KM a year for the same services.

Izetbegović refused to meet with CIN reporters.

Creation and Disbanding of Pathology Department

The previous hospital management headed by Dr. Bakir Nakaš created a team of pathologists made up of the seasoned physicians and a young specialist. When Izetbegović took the hospital’s helm in March 2013, the Pathology Department had three physicians and five technicians. The doctors were: Amina Ahmović, still specializing; Ivana Tomić-Ćuk, a retired physician hired under a personal services contract, and Zrinka Vidović who soon after died. They examined around 3,500 tissue samples a year, studying the manifestations of disease, especially in patients suffering from cancer. The quality of this service significantly influences medical treatment.

Dr. Tomić-Ćuk could not be hired full time because she was a pensioner, so she entered into a personal service contract every month. When her contract run out in June 2013, Izetbegović did not offer her another. “I was just informed that my contract ended,” said Tomić-Ćuk.

Izetbegović informed the Sarajevo Canton Health Care Fund that hiring under personal services contracts contradicted decisions of the Sarajevo Cantonal government and its assembly and she added that the Department of Pathology just had one physician specialized in the field.

In July 2013, Ahmović finished her specialization. According to a contract that she had earlier signed with Nakaš, Ahmović was bound to work at General Hospital for four years after completing specialization. In August 2013, she signed a four-year contract with Izetbegović.

Just four months later, Ahmović asked the directress to discharge the contract by mutual consent. Izetbegović accepted her notice of termination and hence renounced the hospital’s investment into the doctor’s specialization. The hospital was left without a pathologist.

Ahmović refused to talk to CIN reporters. “No way will I comment on the subject,” she said.

On the same month when Ahmović left the General Hospital, Izetbegović rented part of the hospital to Talirević’s private clinic. An agreement on 754.5 square meters was signed in March 2014. My Clinic pledged to pay an annual rent of 127,118 KM plus utilities.

The space needed some reconstruction, so the hospital and My Clinic agreed to do it jointly. The hospital invested nearly 63,000 KM. The paperwork that CIN received did not specify what My Clinic invested.

Talirević said that he would have earned more if he had opened the clinic somewhere else.

“But, first off, we had an intention, to build something that would last beyond us in case we have left,” he said.

Five months after Ahmović was gone, the hospital put out a vacancy to hire two pathologists, but no one applied. The health care fund then allocated additional money to the hospital to procure histopathological services. Along with its regular budget for 2014, the hospital received another 820,000 KM for this.

Former general manager Nakaš said that during his term the hospital never received Fund’s money for the pathology department.

“During the whole time, from when I started building the Pathology Department until I retired, I have not received a cent for pathology. I paid it all from the regular budget,” said Nakaš.

This is not the first business deal Talirević concluded with public hospitals in Sarajevo. His clinic earlier did tissue testing for the Clinical Center of Sarajevo University when Faris Gavrankapetanović was its general manager. After he was appointed the Center’s director in 2012, Gavrankapetanović put out a bid for histopathological services which stipulated that only private clinics could compete. Talirević’s clinic was the only private health care provider dealing in these services at the time, and it collected nearly 1.8 million KM in histopathological services from the Fund.

Tenant on a Tender

With additional money, General Hospital moved to procure histopathological services. Izetbegović put out a first bid, worth 600,000 KM, in May 2014. My Clinic was one of three clinics that put in an offer and its was the lowest price. The offers of the other two clinics were rejected for lack of required paperwork.

Still, Talirević’s clinic did not get the contract. The call was voided due to the lack of eligible bids. When a second call for bids went out, My Clinic was the only one to send in a bid.

A day before Talirević was to send in his bid, his clinic and General Hospital organized a gathering of staff. Amid snacks, the general managers of two health-care providers announced future collaboration.

Six days later, Izetbegović awarded a contract worth 513,000 KM to Talirević. In April 2015, she signed a new contract with My Clinic. There was no public bidding. Instead, Izetbegović negotiated with Talirević to pay him 170,000 KM for four months.

A new tender for the year 2015 was put out in June. Again, Talirević’s clinic was the only one to apply and it received a contract worth 430,000 KM. According to the contract, My Clinic was supposed to work for the General Hospital until the end of March 2016.

Izetbegović did not get to see the end of the contract as she was appointed the general manager of the Sarajevo University Clinical Center in the beginning of 2016.

In February 2016, the hospital’s new management put out a tender for histopathological services. Talirević and The Sarajevo School of Medicine applied. The School’s offer was 94,215 KM cheaper. Even though the cheapest price was the main criteria, the School did not get the contract. The tender was voided “for reasons outside of this agency’s control.” The hospital has not explained in detail what those reasons were.

The School, but also My Clinic, complained to the BiH Procurement Review Body. The Body accepted the School’s complaint and awarded it a contract. Talirević complained again, and the case is ongoing.

Over two years, Talirević collected more than 1.1 million KM in revenue. Prior to his deal with the General Hospital, the costs of salaries, chemicals and other necessary material for the work of the Department of Pathology over five years totaled around 840,000 KM.

Talirević said that he gave a discount to the General Hospital, but the price of testing in his clinic is higher because he had to factor in the cost of heating, rent and wear-and-tear.

“We’re a for-profit organization. We have to make a profit – we have not come out here just to break even,” said Talirević.