Key Points:

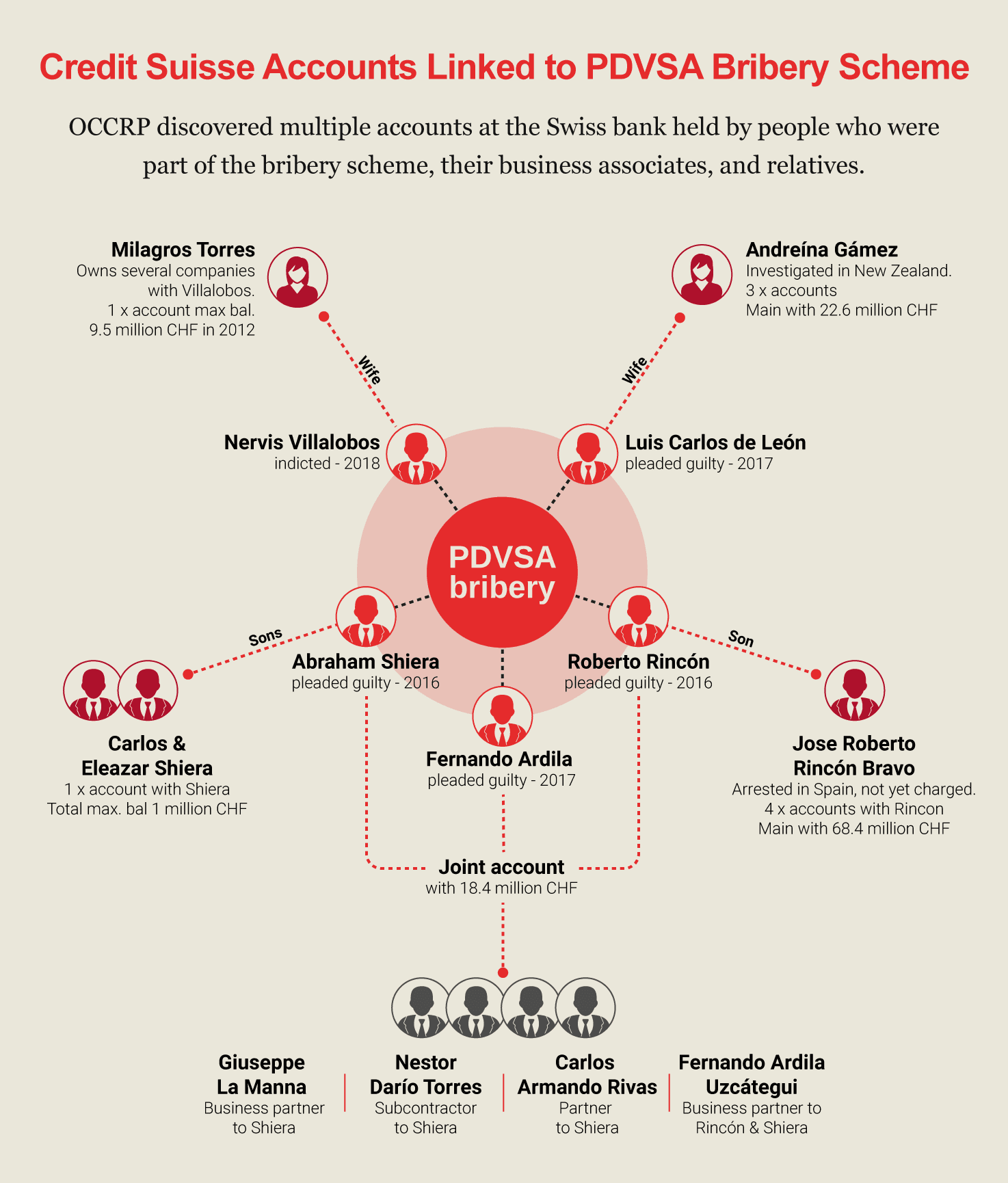

- More than two dozen Venezuelans linked to four corruption schemes in the state oil company, PDVSA, amassed assets worth at least $273 million in 25 accounts.

- Nearly all of them were opened between 2004 and 2015, when billions of dollars were embezzled from PDVSA, including for people who had already been publicly implicated in corruption schemes.

- At least a dozen of the accounts — which belonged to people implicated in the schemes, their family members and business partners — are not mentioned in court documents.

From his small motorboat, Roberto has watched the rise and fall of Venezuela’s oil industry. For a decade he has ferried workers across Lake Maracaibo to the vast production facilities that line its shores, which were once the jewel in the crown of the country’s national oil company.

But as the industry has collapsed, so too has Roberto’s livelihood.

“Everything has changed… it’s over,” he told OCCRP, requesting reporters refer to him using a pseudonym for fear of retribution.

Once the driver of one of South America’s strongest economies, the state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) has been hollowed out by mismanagement and corruption. Oil executives and their cronies have looted at least $11 billion from the company in a slew of scandals involving fraud, bribery, and currency scams.

Now, reporters have located the fortunes some of them have secreted away in Switzerland. Leaked banking data reveals that more than 20 Venezuelans linked to four PDVSA corruption schemes amassed assets worth at least $273 million in 25 accounts at Credit Suisse over the years – and likely much more. In some cases, the accounts contained significantly more money than authorities have made public.

Using court documents from Spain, the U.S., and Andorra, OCCRP mapped the key players in these bribery and kickback schemes. Reporters then combed through thousands of banking records to find where they had hidden their money, discovering at least a dozen Credit Suisse accounts that have never been named in court documents. These included bank accounts involving 12 associates and family members of people implicated in one of the scams.

Nearly all of the accounts were opened between 2004 and 2015, which covers the period when these PDVSA corruption schemes were taking place. Some accounts remained open even after their holders were arrested, charged, extradited, pled guilty to serious financial crimes, or were named in the media as giving or taking bribes.

The Suisse Secrets Investigation

Suisse Secrets is a collaborative journalism project based on leaked bank account data from Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

The data was provided by an anonymous source to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which shared it with OCCRP and 46 other media partners around the world. Reporters on five continents combed through thousands of bank records, interviewed insiders, regulators, and criminal prosecutors, and dug into court records and financial disclosures to corroborate their findings. The data covers over 18,000 accounts that were open from the 1940s until well into the last decade. Together, they held funds worth at least $100 billion.

“I believe that Swiss banking secrecy laws are immoral,” the source of the data said in a statement. “The pretext of protecting financial privacy is merely a fig leaf covering the shameful role of Swiss banks as collaborators of tax evaders. This situation enables corruption and starves developing countries of much-needed tax revenue.”

Because the Credit Suisse data obtained by journalists is incomplete, there are a number of important caveats to be kept in mind when interpreting it. Read more about the project, where the data came from, and what it means.

Critics say Credit Suisse’s role in enabling corruption schemes in Venezuela and other countries is not just an internal problem; it’s also related to Swiss laws that encourage stringent banking secrecy and punish whistleblowers.

“The Swiss banking system remains a favorite destination not only for the proceeds of massive bribery schemes like the ones involving PDVSA, but for the use of companies like PDVSA as vehicles for laundering criminal proceeds,” said Alexandra Wrage, president of the anti-corruption nonprofit TRACE.

But as corrupt elites have filled their pockets, it is ordinary Venezuelans who have paid the price. The country’s economy has cratered since 2013, with high levels of poverty, unemployment, and hunger, while hyperinflation has eaten into both the savings and the salaries of those lucky to still have them.

Lake Maracaibo, a lagoon in Venezuela’s northwest coast, is a stark reminder of the costs of that corruption. When a reporter visited in November, soda bottles floated in the dirty water and a Hello Kitty doll covered in black sludge had washed ashore. Many of PDVSA’s gigantic facilities along the coast now lie abandoned and overgrown with weeds.

Roberto, who once earned enough for a stable middle-class lifestyle, said that now he can barely afford to feed his family. He’s thinking of joining the 6 million Venezuelans who have fled the country since 2015.

“What’s the use of having a fatherland if people are in need?” he said, using a term frequently invoked by Chavistas to encourage patriotism. “What’s the use of having my family here together if I don’t have a way to feed them?”

Credit Suisse said its staff had not knowingly facilitated corrupt activities by its clients, and noted that, along with other institutions, it has implemented stricter policies to combat financial crime.

“In line with financial reforms across the sector and in Switzerland, Credit Suisse has taken a series of significant additional measures over the last decade, including considerable further investments in combating financial crime,” the bank said in a statement to OCCRP and other media partners.

“Across the bank, Credit Suisse continues to strengthen its compliance and control framework, and as we have made clear, our strategy puts risk management at the very core of our business.”

Corruption Pipeline

More than 7,300 kilometers across the Atlantic Ocean from Lake Maracaibo, a former Venezuelan oil ministry official accused of looting PDVSA lives in a 2-million-euro mansion on the outskirts of Madrid, complete with a swimming pool.

It’s been years since Nervis Villalobos has felt the sweltering heat of his hometown, close to the lake’s shore, but he can’t go back. He is facing charges of corruption and money laundering in Spain and neighboring Andorra, as well as the U.S. and Venezuela, which have both filed extradition requests.

As a key middleman in Venezuela’s oil industry, Villalobos allegedly received bribes from U.S. companies to help them secure lucrative energy contracts with the national oil company. Spanish prosecutors say Villalobos acted as a frontman for Rafael Ramírez — a previous PDVSA president, a former energy minister, and an ally of the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez.

Spanish court documents say Villalobos’ position made him effectively the second-most powerful person in Venezuela’s Ministry of Energy, where he worked in various senior roles from 2001 until 2006. Even after Villalobos left to become a contractor, he “walked around PDVSA as if he were a senior executive,” said a Spanish judicial source who spoke on condition of anonymity because he is not allowed to discuss the case.

“He would drown your business if you did not pay him. To survive, you had to ally yourself with Nervis [Villalobos],” Mathias Krull, a Swiss banker convicted in the U.S. for laundering PDVSA money, told Spanish prosecutors in a document obtained by OCCRP.

By 2008, Villalobos had started to gain an international reputation for dirty dealings. An 11-page due diligence report commissioned by Credit Suisse’s compliance department that year outlined multiple allegations of corruption against him, including an alleged 2.7-million euro bribe linked to a hydroelectricity project that he split with Ramírez.

But the compliance department’s own report did not stop Credit Suisse from working with him.

In 2009, Credit Suisse’s Monaco branch opened an account for Villalobos, Spanish prosecutors say. Soon after that, another Swiss bank dropped him as a customer due to corruption concerns — so he simply moved the money into his Credit Suisse account instead.

Prosecutors say the Venezuelan funelled almost $25 million and 11.5 million euros through the account until it was closed over four years later. Some of the money allegedly came from bribes paid by Spanish companies for energy contracts that the due diligence report had flagged as suspicious.

Even the personal information Villalobos provided was problematic: When reporters looked up the Caracas address he gave for the account, they found it did not exist.

Then, in 2011, Credit Suisse’s Switzerland operation opened another bank account for him. A text message sent that September shows Venezuelan oil contractor Abraham Shiera Bastidas intervened on his behalf after the bank had questions about the source of the money Villalobos wanted to move to Switzerland. Bastidas would later plead guilty to bribing Venezuelan officials, including Villalobos, for PDVSA contracts.

“The institution has not accepted the stick,” Shiera wrote to Villalobos on Blackberry Messenger, according to the court documents, using Venezuelan slang for large amounts of money. “They are asking me for invoices and purchase orders. I already submitted them. I hope it is resolved tomorrow.”

The message did not name the Swiss bank Shiera was referring to. But the leaked Suisse Secrets banking data show that Credit Suisse opened an account for Villalobos just five days later.

It appears that Villalobos may then have used this account to receive bribes.

A U.S. indictment describes how Shiera and his accomplice, Roberto Rincón, paid $27 million into a Swiss account owned by Villalobos and another Venezuelan, Luis Carlos de León, who in 2018 admitted to being part of the PDVSA kickback scheme. This money was then allegedly funneled into different accounts belonging to Villalobos and de León.

The leaked banking data shows Villalobos and De León both opened accounts with Credit Suisse on the same day in September, as mentioned in the indictment. Within two years, Villalobos’ account was worth at least 9.5 million Swiss francs, while De León’s was worth at least 22.6 million Swiss francs.

Lawyers for Villalobos and De León did not respond to requests for comment. Credit Suisse did not respond to questions about Villalobos or other individual Venezuelans, but the bank’s lawyers rejected the assertion that the institution had inadequate due diligence procedures, or facilitated financial crimes.

“CS does not tolerate or support tax evasion, money laundering or other illegal activities, has stringent control mechanisms in place and reviews and develops its policies on an ongoing basis,” the bank’s law firm, Latham & Watkins LLP, said in a letter.

Newly Discovered Accounts

In total, reporters identified sixteen Credit Suisse accounts containing at least 162.9 million Swiss francs belonging to seven people who were convicted or accused of being involved in this PDVSA kickback scheme. In one case, the data appears to shed fresh light on an ongoing investigation.

José Roberto Rincón Bravo is the son of Roberto Rincón, who admitted bribing PDVSA officials alongside Shiera in a U.S. court in 2016. Spanish police arrested Rincón Bravo in 2018 on suspicions he laundered PDVSA money, confiscating jewelry, watches and sports cars from him and his family, and seizing a 400-hectare estate near Madrid with several houses and a large paddock for horses.

Rincón Bravo has not yet been charged in the case, however, and he has publicly denied being involved in his father’s corrupt affairs. In 2019 he told El Confidencial, a Spanish newspaper, that his expensive accessories came “from work, from years of savings.”

But the Credit Suisse data shows Rincón Bravo and his father held four joint accounts worth at least 93 million Swiss francs that have not been named in any court documents before now. Three of the accounts reached their maximum holdings barely two weeks before Rincón Bravo’s father was arrested in December 2015.

Many of the Credit Suisse accounts were jointly owned between people involved in the scheme and their family members. Another two belonged to people who worked closely with Rincón and Shiera as PDVSA contractors. In total, reporters found seven people associated with suspects had accounts, which at their maximum held a total worth at least 20.1 million Swiss francs.

And those weren’t the only accounts linked to PDVSA corruption schemes that OCCRP found in the data.

While scouring the leaked banking records for details on Villalobos, reporters also found people related to another massive fraud in which he was involved. This scheme used fake invoices to siphon off an estimated $2 billion of Venezuelan oil wealth, which was allegedly laundered through Banca Privada d’Andorra, in the tiny mountain principality between Spain and France.

Again, Villalobos is accused of using his position to extract kickbacks from foreign companies in return for PDVSA contracts. This time he allegedly worked with Diego Salazar, a cousin of the former oil minister, Ramírez. Salazar is now in prison in Venezuela over the corruption, while Villalobos has been charged over the Andorra scam. He has so far evaded extradition.

Another middleman, Jose Luis Zabala, had at least 7.5 million Swiss francs in the bank.

Neither man responded to requests for comment.

Trail of Venezuela’s Stolen Billions Leads to Caribbean Luxury Properties

Read more about Jose Luis Zabala

A Bribery Case Closer to Home

Two other Venezuelan businessmen, Francisco Morillo and Leonardo Baquero, also held Credit Suisse accounts — despite being investigated in an ongoing bribery and money laundering case in Switzerland.

Swiss prosecutors are looking into allegations that they ran a scheme to fix prices and rig bids for PDVSA oil sales, which PDVSA officials said cost the company “billions of dollars in losses.”

Documents from a separate U.S. case against them, which was dismissed in 2019 as the judge deemed the court did not have jurisdiction, show Baquero and Morillo are accused of bribing several PDVSA officials to help them clone a company server. They then allegedly used the inside information they gleaned to cash in on sales to global commodity traders like Trafigura AG, Vitol Energy, and Glencore.

The leaked bank records show the men accumulated assets worth at least 71 million Swiss francs in several Credit Suisse accounts between 2012 and 2014, including one shared with Yanira del Valle Marcano Alfonzo, one of Baquero and Morillo’s alleged accomplices, who worked at their oil brokerage firm.

When asked about his client’s relationship with Credit Suisse, Morillo’s lawyer in Switzerland, Jean-Marc Carnicé, only confirmed that his client was under judicial investigation in that country and has “fully cooperated” with the process. Leonardo Baquero’s lawyers did not respond to questions from OCCRP and its partners.

A more recent case relates to Naman Wakil, who was arrested in Miami in 2021 over charges of corrupt dealings with Venezuela. Between 2010 and 2017, U.S. prosecutors say he bribed his way into at least $30 million of contracts with PDVSA and some $250 million with Venezuela’s state food company.

Authorities say Wakil then moved some of his ill-gotten wealth into Miami real estate, including apartments on the beach as well as downtown high-rise apartments. Millions more were allegedly splashed on a yacht and plane.

The court files say the stolen funds were laundered through accounts in the U.S., Cayman Islands, Panama, and Switzerland. OCCRP found Wakil opened an account with Credit Suisse in September 2011, which three months later was worth 3.7 million Swiss francs.

“The Swiss banks were the most prevalent” in the Venezuela corruption schemes, said lawyer and former U.S. prosecutor Michael Naddler, who worked on some of the cases. “Whether they were complicit or not, they, I would tell you, allowed a lot of this to happen.”

“Traditionally, Swiss banks have been the banks who keep secrets the most and the best.”

Graham Barrow, an independent expert on financial crime, said it encourages corruption when banks allow stolen funds to enter the global financial system.

“If the banks will not stop conspiring with these people to legitimize funds that should never be legitimately put into the system, we are never going to change,” he said. “People in Venezuela, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere will remain poor.”

Corruption and Crisis

No one knows how much money was looted from Venezuela’s national oil company. Estimates range from $11 billion to $300 billion from 2002 to 2014 alone, after Chávez came to power and when oil prices were booming.

But the effects of the economic meltdown have been catastrophic. Food price inflation reached a “staggering” 1,700 percent in 2020, the World Food Program said, while the poverty rate hit 94 percent last year. As Venezuela sank into a humanitarian crisis, oil money that should have paid for schools and hospitals was being funneled into offshore accounts.

“In the last 18 years, PDVSA went from bad to worse. From the implausible to the absurd,” said César Mata-García, a Venezuelan lawyer who focuses on the energy industry.

The effect of PDVSA’s corruption is evident in the dilapidated ghost towns on the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo, where streets bustling with oil workers and their families have been replaced by graveyards of abandoned cars. All around the area, a constant reminder of the company’s decline leaks steadily into the water.

“Estimates are that between 60 and 80 barrels leak from wells and pipes daily into the lake,” a senior PDVSA employee told OCCRP. He requested anonymity for fear of reprisals from the oil company.

David, a scuba diver specializing in the maintenance of underwater equipment, who declined to give his full name for fear of retribution, said the company used to have about 50 boats that would constantly ferry repair crews around the lake.

“Years ago, I could cover an average of 17 leaks per day,” he said, adding that none of those boats work anymore. “More than 20 have sunk, and many others are missing pieces.”

But even though they live in the center of oil production in a country with the world’s largest oil reserves, residents of Maracaibo are struggling to buy fuel. Shortages became so dire in 2019 that the state government imposed rationing, leading to a desperate scramble for supplies.

Just before sunrise one November morning in Maracaibo, at least 100 cars were parked near a gas station. Drivers had received a message warning it would receive a delivery that day, and waited on tenterhooks in the hope of buying up to 30 liters of fuel. Chaos soon ensued as the vehicles converged on the pumps with their horns blaring, in an exercise locals call “Rapido y Furioso,” after the Fast and Furious movie franchise.

Residents of Zulia state lamented having to scramble for fuel in a region so rich with oil. Luis, who worked building the piles that support the rigs in Lake Maracaibo before losing his job in 2005, said oil used to form puddles on the ground.

“I remember walking barefoot and arriving with my feet stained with oil,” said Luis, who now works in a car repair shop. “It welled up, like sweat wells up from the skin.”

“We in Zulia have sustained Venezuela. We have given too much for the little we have received. And the saddest thing is that we’re standing on oil.”

InfoLibre, the Miami Herald, and NDR contributed reporting.

The OCCRP’s story READ HERE.